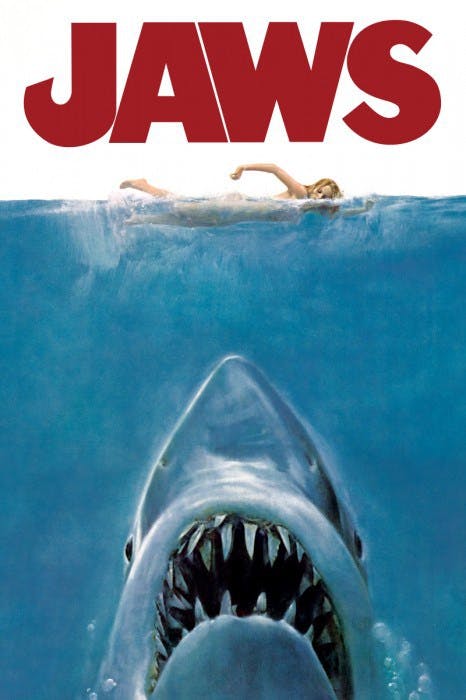

Jaws (Universal)

The ads show a gaping shark’s mouth. If sharks can yawn, that’s presumably what this one is doing. It’s certainly what I was doing all through this picture, even in those few moments when I was frightened. There’s no great trick to frightening a person: anyone can do it by jumping out of a closet at you—which would be both tedious and irritating at the same moment that your heart skipped. Thus with the few scary moments in this film.

The publicity has emphasized the ingenuity in the construction of the artificial shark used in Jaws. Well the shark is the best constructed element in it. The script comes from a novel by Peter Benchley, who also worked on the screenplay. There was also much publicity about how the novel was constructed and revised to suit the publisher, the script for the producers. Fine. No one expects a scare film to breathe Shelleyan purity, but need the stitching and the padding be quite so obvious? If the story isn’t clear enough for you—“you” meaning a retarded chimpanzee—the producers have laid on a noisy score by John Williams that tells you when trouble is coming and when you’re supposed to be excited.

A killer shark depredates the beach of an island summer resort. Several people are killed. Finally the shark is killed. That’s the story. But to fill it out for two hours we get stuff about the island police chief and his wife; a mayor who wants to hush things up for the sake of business; a knowledgeable young ichthyologist and his tussles with a salty old shark-hunter; etc. At last the mayor admits the crisis so the police chief, the young man and the old pro go hunting for the shark. They catch him, but he catches the old pro, in a sort of Moby-Dicklet sequence.

The only performer worth mentioning is Robert Shaw as the old pro and I mention him only to hope that he is getting rich. This good actor certainly ought to get something out of all the non-acting he’s doing these days. The direction is by Steven Spielberg who did the unbearable Sugarland Express. At least here he has shucked most of his arty mannerisms and has progressed almost to the level of a stock director of the ‘30s—say, Roy del Ruth.

Rollerball (United Artists)

I used to read a lot of science fiction in the 1950s in connection with editorial work, and even then there were a number of worn clichés that only really imaginative writers could usefully employ. One of them was a future society in which deplorable traits of the present had been exalted, rendered into codes and rituals. Now comes a film with a script by William Harrison that lolls lazily back right in the middle of this sci-fi cliche.

Rollerball is the name of a popular game in the not-too-distant future, a vicious game played on roller skates on a sort of enlarged roller derby track, using a heavy steel ball and a few motorcycles. The players wear spiked gloves like the Roman gladiatorial cestus; bad injuries, even fatalities, occur. The game is played internationally between cities—for instance Houston against Tokyo—before huge crowds. The idea is that the blood hunger of peoples produced the game which is now promoted and managed by great international syndicates to drain off aggression and keep people controllable.

Few high school English teachers who have read the above paragraph will fail to be reminded of stories they have seen by bright students.

The plot centers on the efforts of one syndicate to force a star player to retire, presumably because he is becoming the center of a personality cult (although this is unclear—the syndicate has also publicized him greatly). Norman Jewison directed at about the Spielberg level. The real star ought to have been the art director, but Robert Laing doesn’t do much more than one would have expected.

The star is played by James Caan—Mr. Nothing in excelsis—so it’s a bit hard to credit him as a saving remnant of human spirit standing out against regimentation. The head of the syndicate is John Houseman, who showed in The Paper Chase that he knows how to exhibit his personality skillfully, which many people called fine acting. Here he continues as a personality performer in a slightly modified key. Houseman may become the new Sidney Greenstreet.

In the course of his rebellion Caan visits the world information bank in Geneva where he talks to a computer-god reminiscent of HAL in 2001, The head librarian is Ralph Richardson who plays the nondescript short role with great good cheer. Why not? He probably got a great good check.

The Drowning Pool (Warner Bros)

Paul Newman certainly got a good check for this one. He’s not only one of the stars, he’s one of the producers. And his wife, Joanne Woodward, is in the film. The family must have done OK.

Forgive my dwelling on money this way, but most of the time during these three pictures, all I could think of was that someone was getting something out of them and it wasn’t I. Let these people make 10 times what they got if only they give me something in return for watching their flicks. I’d have liked to see Newman in a good suspense picture—Harper, the antecedent of this one, was better. But to watch a bad suspense film, to watch a bad category film in any category (or, as it’s called now, genre) seems more wasteful than other kinds of bad films.

This one was made from a novel by Ross Macdonald that I haven’t read, but he’s generally been better than he’s made to look here. The director was Stuart Rosenberg, never exactly light-fingered yet he made the very pleasant Pocket Money. Before three minutes are up you know you’re in for a lot of sententious imitation Chandler: a private eye getting into a situation that is supposed to evoke moral resonances for our time. But it doesn’t have the usual tight beginning of suspense films that usually come unglued; this one begins unglued.

Newman arrives in New Orleans from Los Angeles to work for a rich woman (Woodward) he once had a fling with. She has a nympho teenage daughter. (Bed-busy adolescents are in, this season; see Night Moves.) (No! Don’t see Night Moves.) There’s a rich autocratic grandma, the good English actress Coral Browne, who gets bopped too soon to be interesting. There’s a local detective chief played by Tony Franciosa, who has never been more negligible, which is some sort of summit. And there’s the imitation-Chandler tycoon, played by Murray Hamilton who was the mayor in Jaws and is equally unimpressive here.

The laughably tenuous plot has its climactic scene in the tub room of an abandoned mental hospital. Hence the title. The whole script has labored toward that “hence.”

Newman and Woodward have complained publicly about the scarcity of good scripts. But did they have to prove the point at this length?