Near the very end of Luchino Visconti’s 1960 film Rocco and His Brothers, the factory siren of an Alfa Romeo plant on the outskirts of Milan sounds, indicating that it’s time for Ciro—one of Rocco’s brothers—to return to work. Ciro is the “good” brother, the one who found a way to live in industrial northern Italy: He accepts his social position as an unskilled worker, marries a nice local petty bourgeois girl, and lives cleanly. Ciro has just reported his brother Simone to the police, while Rocco has gone off to pursue a career in the brutal world of professional boxing. The family is shattered and dispersed. The youngest brother, Luca, hopes to someday return to the southern region of Lucania, where they’re from.

Why would they have left Lucania to begin with, a world where you relax in the sun, go to the beach, take a tomato from the vine when you’re hungry? There was chronic under-employment in the south. The soil was of poor quality. After grain markets were deregulated, prices plummeted. For rural populations in the Mezzogiorno, there was simply no future.

At the same time, the Italian postwar economic “miracle” meant there were jobs in the factories of the rapidly industrializing north. Between 1951 and 1971, nine million people migrated from rural to industrial areas in Italy. They often arrived in the big cities with nothing, and were forced to live in train station waiting rooms or on relatives’ floors. They worked day and evening shifts on building sites or in factories that offered treacherous conditions and long hours.

This history is all deftly evoked in Visconti’s film, which ends after the southerners return from lunch to their shift on the assembly lines of Alfa Romeo. And yet the saga is not over. It is far from over. The end of the film opens outward to the portents of the future. To what was to come, and eventually did come.

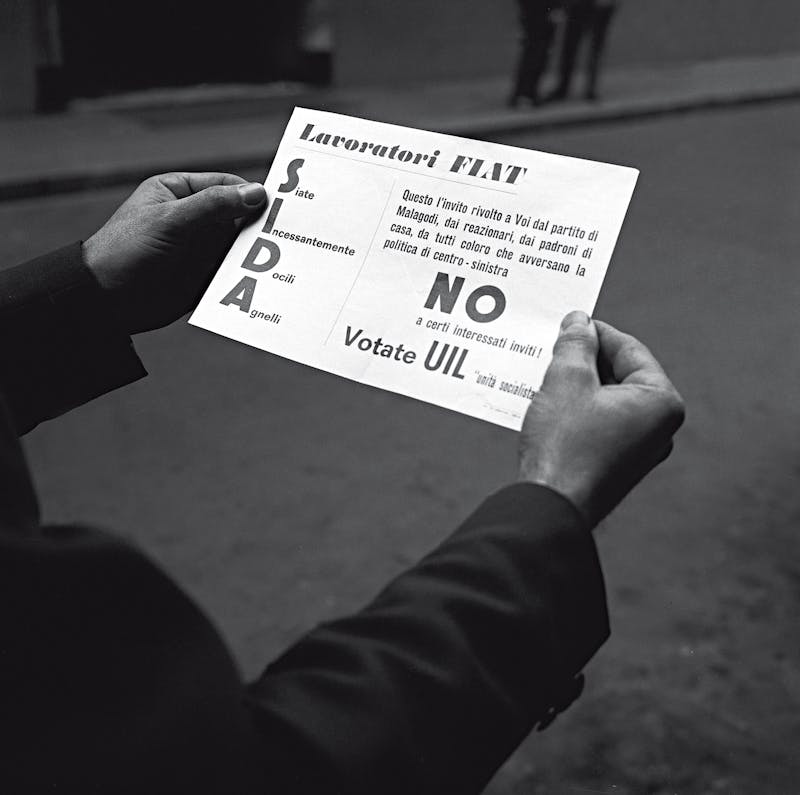

Almost a decade later, in 1969, the workers from the south on the assembly lines of the north revolted in waves of wildcat strikes and violence. This was a new movement, of workers that rejected the values of classic worker organizations, and most especially the Communist Party, which was regarded as a blockade to real change, an organ of compromise with company bosses. These workers were ready to reject the entire structure of northern life and of work itself. Their revolt was an all-out assault on their own exploitation. They wanted everything, as their placard slogan and shop floor chant famously expressed, Vogliamo Tutto!

We Want Everything, by Nanni Balestrini, is a novel of great energy and originality that succeeds on three different levels: as a work of astounding art, a document of history, and a political analysis that still resonates with the contradictions of the present. Published in Italy in 1971, the novel has not appeared in English translation in the United States until now. Its artfulness lies in the tone: The person who speaks in the first person in this novel is nameless, but not at all unknown to us. He is intimate, insolent, blunt. He’s full of personality, full of humor, and rage. He speaks in a kind of vernacular poetry that gets into the mind and stays there. “All this new stuff in the city had a price on it,” he says, “from the newspaper to the meat to the shoes; everything had a price.”

His story is likely that of a real person, named Alfonso Natella, to whom the book is dedicated. Perhaps crucially, the protagonist speaks in a vaguely testimonial form to those who were not there. He was there, and he knows we, his readers, were not, and so he gives us a full account of his life. The book in its entire first half is something like a dossier, and we know the dossier matters: It’s the case file of someone who was witness to the clashes and convulsions of his own historical era.

Our hero arrives in Turin and is lucky enough to have a place to sleep at his sister’s, while many of the “great tide” of southerners washing into the city are living in the second-class waiting room at Porta Nuova train station, which would admit anyone with a Fiat ID card or a letter from Fiat stating that he had an interview at the factory. The police patrolled the train station vigilantly, but they weren’t on the lookout for loiterers and squatters. The police were looking for journalists, making sure they didn’t get anywhere near the second-class waiting room, “this dormitory that Fiat had, for free, at the Torino train station,” as the protagonist says.

At the Fiat plant, he seeks employment along with 20,000 other new hires. “The monsters were coming,” he says, “the horrible workers.” And their monstrosity is magnified by the high demand for labor. The work was so unbearable, many workers left after just a few days. Some withstood only half a day before choosing destitution over the demands of the assembly line. The protagonist is part of this tide of necessary monsters, hated that much more because the factory must hire them, must deal with them.

He goes through an interview process that is a pantomime (everyone is hired), then a factory medical assessment, which is even more comical and absurd. The protagonist endures muscle-strength testing on newfangled machinery, a blood test in a room that features high piles of stinking, blood-soaked cotton balls, a piss test that the men prepare for in a circle, “making beer,” as they joke, and then finally, the doctor’s examination, in which the protagonist, for the hell of it, seeing that the whole thing is a charade, announces that he is missing one testicle.

He’s hired despite his lie. “Maybe they wouldn’t have taken a paraplegic,” the protagonist speculates. But the medical exam has not been entirely a charade. It seems instead a necessary stage in these workers’ exploitation: They are handing over the rights to their sole possession—their bodies—to the bosses of Fiat, transferring ownership of their selves to the factory. So when the protagonist claims to the company doctor that he’s only got one ball, he is throwing them an insult, telling them that their new body on the line is faulty; it’s not even a full man!

On the assembly line, the real fun begins. The work is backbreaking, and in this era, wages were tied to productivity, meaning workers didn’t get a decent base wage; they could not earn enough to live on unless they produced a certain profit margin for the company. At one point our protagonist is put on a line where the work requires use of just one shoulder to rivet with a heavy pneumatic gun, a repeated motion that will deform him by twisting his back and bulking his muscles asymmetrically. Meanwhile there are some on the assembly line who are dedicated to work and to the Communist Party, northerners from peasant backgrounds, “really hard people, a bit dense, lacking in imagination,” who spend their whole short lives working. People for whom “work was everything.” To the narrator, they’re worthless. “Only a drone,” he says, “could spend years in this shitty prison and do a job that destroys your life.”

The protagonist gets sick leave, but realizes that he has no idea what to do with himself, how to relax or what to do in Turin. The factory not only degrades work, it degrades life away from work, too. This is alienation, the lived experience of exploitation, but it is demonstrated here without theoretical abstractions: It’s an oral account of a person’s life, that’s all.

At a turning point, the narrator decides to dedicate himself totally to making trouble. It’s a commitment to risk everything. “I didn’t want Fiat,” he tells the bosses. “I didn’t make it, I’m inside here just to make money and that’s it. But if you piss me off and break my balls I’ll smash your heads in, all of you.”

And so the struggle begins. But the protagonist’s threat, that scene, is not a moment of singular heroism. As literature and history both, We Want Everything is not a story of one remarkable man. It’s the story of the nameless and unknown who went north, like Rocco and his brothers and like the 20,000 who were hired the month the protagonist was hired, in 1969. It’s the story of the men who worked these awful jobs and got fed up, directed their rage and their strength and violence, in the interest of no longer living in misery.

The women would not have their say quite yet: This struggle was about men and their exploitation. Women—exploited doubly in Italy, in the piece work they did at kitchen tables for the factories in the north, and by their families for their domestic labor—would have to mark out their own path, and did. In fact, it’s accurate to say that feminism had the most lasting and successful impact among the demands made in the revolts of 1970s Italy. But women’s demands were not part of the “everything” in this everything of factory revolts, a reminder that the word has limits, a context. “We want everything” meant we want to live lives with meaning, and we refuse to be forced to work in order to survive. It was a working-class male “everything”; women would still be at home toiling away, even in the case of unlikely victory.

The second part of the novel opens with a chapter on wages, and marks the narrator’s transformation into a theorist of his own struggle. He sees that, as a worker whose wages are tied to productivity, he collaborates with the bosses against himself. The tone makes a subtle shift. The “I” partly dissolves, and the book becomes something like pirate radio news bulletins of the war on the factory, the war in the streets. The struggle expands. The narrator, wherever he is now, is part of a new collective desire, calling not for higher base pay but for the abolition of capitalism, for the bosses’ economy to collapse.

I once asked a friend, an Italian from Milan who seems to know a lot of people, if he’d heard of Nanni Balestrini. My friend is in the art world, and I wasn’t sure if he would have read Balestrini’s work. We were in this friend’s kitchen. He was making me a salad. He said “Balestrini!? Nanni? But I helped him escape into France!”

It turned out that, in 1979, when Balestrini was going to be arrested for so-called insurrectionary activities against the state, as so many were, this friend outfitted him with skis and ski gear. He drove him to the Italian Alps, and then crossed into France and waited for Balestrini to ski down on the other side of Mont Blanc, into Chamonix. I pictured the one photo I’d seen of Balestrini, a man wearing a scarf wrapped in a complicated and elegant manner, a person who looked more bohemian and urbane than athletic. I asked, “But does Balestrini ski?” My friend held out his hands in emphasis, and said, “You know … good enough!”

Balestrini had been a founding member, in 1968, of the extra-parliamentary left-wing group Potere Operaio, whose focus was on factories and factory workers, on listening to workers and producing a movement of their voices and direct experience. It’s likely that Balestrini was outside the gates of Fiat in 1969. (Alfonso Natella, the subject and “ghost author” of this novel, was also involved with Potere Operaio, which is surely how they met.) This method of workers’ inquiry—called inchiesta by its practitioners in Italy—has foundations in Marxism. But it only truly took hold in postwar Europe, particularly in the tactics and tenets of the radical left French group Socialism or Barbarism, which then influenced workerist theory—Operaismo—in Italy.

Worker subjectivity, it became apparent, was shifting away from building a labor movement and toward a resistance against the disciplines of work. The concept of collecting the stories of workers themselves, the idea that their accounts of work and of their lives would be essential to any revolutionary process, goes all the way back to Marx’s 1880 worker’s questionnaire, which was meant to be disseminated among French factory workers. “It is the workers in town and country,” Marx wrote, “who alone can describe with full knowledge the misfortunes from which they suffer.” Simply put, there is no theory without struggle. Struggle is the condition of possibility for theory. And struggle is produced by workers themselves.

But in its use by Balestrini, who was not just a militant and theorist but a poet and artist, a writer to the core, inchiesta became something more, something else: a singular artistic achievement and a new literary form, the novel-inchiesta. Balestrini went on to employ this same method in later novels, Gli Invisibili (The Unseen) and Sandokan. Both feature first-person protagonists who tell stories that serve also as historical accounts: of the militancy of the autonomist movement of 1977 in the former; of the Camorra and its ravages of the south in the latter.

These voices in Balestrini’s novels are always one person speaking anonymously as a type. The voices have all the specificity of an individual—a set of attitudes, moods, prejudices, back stories—but they each speak in a way that exemplifies what life was like for a person such as them, in a moment when there were many like them. They are works that capture and illuminate voice. Voices speaking, rather than words written. In this way, these works depart from the classical subjectivity of the nineteenth-century novel, and seem closer to an earlier tradition, also oral and heroic and historic: epic poetry.

We need many epics for each epoch. Perhaps one day we will finally have the testimony of Balestrini’s own life, his own I as an any and a we, his militancy and flight. In the creation of We Want Everything, he dissolved himself, became the mere medium through which Alfonso Natella speaks. As if Balestrini had rolled under the factory gates, like smoke, and was suddenly inside. Perhaps the novel-inchiesta is never a work of introspection, but always instead of refraction: a way to refract that which, as Umberto Eco wrote of this novel, “is already literature” before its refraction, its transcription, before its existence in a book.

This novel was already literature when it was in the form of the passing thoughts a worker was having on the assembly line. I’d like to think that Balestrini skiing down into Chamonix, his scarf flapping, whether told or not, is literature, too.