Girls, women—what do they desire? “To have fun,” Cyndi Lauper advised. Freud was baffled; he called it “the great question that has never been answered and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my 30 years of research into the feminine soul.” Hollywood answered the question by making Mel Gibson read women’s minds. Mary McCarthy sent them to Vassar. Lena Dunham took them to party in Bushwick. Mostly, though, female desire is a mystery no one rushes to solve. One vastly ignored area of desire is the kind depicted between two women—not so much sexual desire, but more a sense of identity and projection. Women speak of crushes on other women. Admiration is a form of coveting.

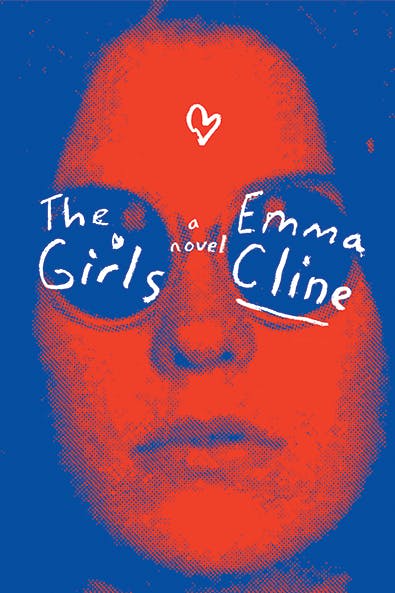

In The Girls, Emma Cline’s highly anticipated debut novel, Evie Boyd, a 14-year-old living in the sleepy city of Petaluma, California, desires a new life. It’s summer in 1969, and swimming pools are the shape of kidney beans, and vegetables are cooked to the color of ash. Not too far away, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury is filled with hippies and runaways. The scent of patchouli drifts through the air, while acid tabs melt on tongues. Petaluma, with its ranch houses and suburban complacency, is a less excitable place, but the center of Evie’s life no longer holds. Her father has left for a younger woman, and in the aftermath of the divorce, her mother is too self-absorbed to notice her daughter’s unhappiness. In the fall, Evie will be sent off to an all-girls boarding school. In the meantime, her days are aimless, spent on how to make herself desirable:

Every day after school, we’d click seamlessly into the familiar track of the afternoons. Waste hours at some industrious task: following Vidal Sassoon’s suggestions for raw egg smoothies to strengthen hair or picking at blackheads with the tip of a sterilized sewing needle. The constant project of our girl selves seeming to require odd and precise attentions.

Beauty is a project. Evie tests her makeup in different lights (morning, dusk, and night); she mixes face masks out of avocados and honey; she dresses “to provoke love.” Doing anything else—reading, say, or writing—is unimaginable. “As an adult, I wonder at the pure volume of time I wasted,” as she puts it. “The feast and famine we were taught to expect from the world, the countdowns in magazines that urged us to prepare 30 days in advance for the first day of school.” But this, Cline implies, is the tax for being female. What Evie wants is to be wanted. “I waited to be told what was good about me,” Evie says.

Then one day in this long, languid summer, Evie is seduced. She glimpses three young women she’s never seen before, dumpster diving outside of a restaurant. Their beauty is unconventional, maybe even a little feral. Suzanne, their ringleader, stands apart:

Her black hair marking her, even at a distance, as different, her smile at me direct and assessing. I couldn’t explain it to myself, the wrench I got from looking at her.

The attraction is propulsive. Suzanne belongs to a cult on the fringes of Petaluma’s farmland. (Cline liberally borrows details from the grisly events surrounding the Manson Family.) Russell, their leader, is a charismatic but delusional man who has surrounded himself with young women, all tragically insecure and impressionable—too eager to please, and too easy to groom. Suzanne is more intelligent and self-possessed, but she too falls under Russell’s spell. Evie is desperate for Suzanne’s attention: Does she want to be with Suzanne, or to be like her?

The plot is predictable but not tedious. There’s a Dennis Wilson–Terry Melcher hybrid named Mitch, who has an in with the music industry and a cushy mansion in the city, complete with hot tub. He’s intrigued enough by Russell to supply the ranch with drugs and funds, and vaguely promises a record deal and fame. It falls through. Russell doesn’t respond well to the rejection; the tension builds as summer drifts by. Soon—knowing what actually happened to Sharon Tate at Cielo Drive—one begins to worry more about Mitch’s fate than Evie’s.

Cline provides some comfort by weaving together two chronologies. In the present day, a middle-aged and much more defeated Evie is able to tell us—through a chance encounter with some teenagers—how she became involved with Russell’s cult in the first place. She’s crashing at a beach house on the foggy California coast when its owner’s son, Julian, a college dropout, shows up unannounced. He recognizes Evie as “that lady” from the cult, and while she’s reluctant to sensationalize her past, she’s grateful for the company. She’s also focused on Julian’s teenage girlfriend, the impressionable Sasha:

I could see she was nervous with my eyes on her. I understood the worry. When I was that age, I was uncertain of how to move, whether I was walking too fast, whether others could see the discomfort and stiffness in me. As if everyone were constantly gauging my performance and finding it lacking. It occurred to me that Sasha was very young. Too young to be here with Julian. She seemed to know what I was thinking, staring at me with surprising defiance.

Evie is protective of Sasha. It’s maternal, yes, but it’s also a projection—an understandable impulse, given what happened to her. Soon we’re back in the past with younger Evie, who knows that Russell is sleeping with all the others girls on the ranch. She also knows that he’ll eventually make a move on her. He is predatory and manipulative. “I’m not trying to hurt you, Evie,” he says to her, coercing her into a blow job. “I just want to be close to you. And don’t you want me to feel good?” Evie never says no, but she is too young to know any better. “Was I supposed to cry?” she wonders. And yet: “I liked it, too,” she admits.

This is Cline’s loose brilliance—the helter-skelter dramatization of innocence being lost. The dark intimacy of an older man manipulating a younger woman isn’t shocking. Russell’s desire for Evie, for all her ambivalence, is intoxicating. He has power, and Evie is happy to have a conduit to feeling powerful herself. “You could be pretty,” she realizes, “you could be wanted, and that could make you valuable.”

Still, men are never to be trusted. Present-day Evie is unemployed, unattached, and incapable of intimacy. Has she repressed some form of Sapphic desire as a result of losing Suzanne? Or does she still fear Russell’s return and the threat of violence? Cline provides no answers. Evie’s experience with Russell and Suzanne is so rare that the novel can’t stand as an exemplary examination of female adolescence. Cline is writing more about the lingering effects of trauma than the sexual chaos of the counterculture movement. Although this makes the novel’s historical details and fixation on the Manson cult feel more artificial than inspired—like cheap props in a play—it does create room for something new.

Whether Cline intends it or not, The Girls is a fictional response to the slew of sensational memoirs flooding today’s best-seller lists. This is the literature of valorized victimhood—from Jaycee Dugard’s A Stolen Life to Amanda Berry and Gina DeJesus’s joint memoir, Hope, to Elizabeth Smart’s My Story. Their popularity reveals our obsession with the horror of unimaginable violation, and our naïve belief in recovery. These memoirs start and end the same way. One day, long ago, a young woman’s life changed irreversibly. Dugard, for example, was eleven and walking to a school bus stop when she was grabbed and tossed into a gray car. The last thing she remembers touching was a pinecone. She was imprisoned, raped, and treated like a caged animal for 18 years. Today, she is a survivor. But this kind of storytelling is deceptive. It makes us believe that through forgiveness, fortitude, and the passing of time, you will heal—even though there is little evidence to support this. What of the woman who wants to call herself a survivor, but—either from depression or addiction or some other trouble—can’t?

There’s an admirable, sensuous alertness to Cline’s prose. Sasha is “drained” when her boyfriend removes his arm from her shoulder. Suzanne’s appearance in town has mothers “glancing around for their children,” and women “reaching for their boyfriends’ hands.” When Evie returns from the trailer with Russell after their first sexual encounter, she’s certain that Suzanne can recognize “the inward shift you sometimes see in young girls, newly sexed.” Evie’s father’s girlfriend, a young, uncomplicated woman named Tamar, picks up Evie one evening: “I could tell she wanted to ask questions, but she must have known that I wouldn’t explain.”

Women are constantly tracking each other; they’re never not observing, communicating without words. That Evie’s own mother is incapable of noticing the subtle changes occurring with her daughter doubles as neglect. It’s perceptive, and The Girls pulses with this awareness. Cline has an ear for the barbed and baiting way girls speak to each other. Her dialogue is casual but convincing. Elsewhere, though, Cline’s metaphors land heavily, and don’t help to show the world the way Evie might actually see it. Spaghetti is “mossed” with cheese in an otherwise suburban kitchen. Sun “spiked” through the trees on a summer day. Food is “ferried” to the couch on a quiet night.

Russell is almost beside the point in the end. Evie comes perilously close to being embroiled in murder, but by the grace of deus ex machina, she avoids it. About girls who sound a lot like Evie, Joan Didion in her 1967 essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” wrote:

There are always little girls around rock groups—the same girls who used to hang around saxophone players, girls who live on the celebrity and power and sex a band projects when it plays—and there are three of them out here this afternoon in Sausalito where the Grateful Dead rehearse. They are all pretty and two of them still have baby fat and one of them dances by herself with her eyes closed.

What happens to these girls? They grow up, fade away, move on. It’s the dance of the almost famous. Evie continues to live in the shadows. A man’s desire is thrilling, dangerous, even—but, as Cline shows, it may not be what you really want.