This is one in a series of Potter books, annotating one classic or another (Sherlock Holmes, Mother Goose, etc.) and for those of us who are horror fans, the Dracula book is pure satisfaction. True, it is simply Bram Stoker’s classic potboiler done up in splendid style, but if you admire good book value in these days of high prices, and if you enjoy the great horror story, this Dracula is an exceptional buy. In addition you receive expert annotated commentary from Leonard Wolf, author of Dream of Dracula, which imaginatively interpreted the vampire as an American sex symbol.

Dracula was first published in 1897 and has never been out of print, certainly a tribute to its durability. Over 200 Draculoid books have been produced, as well as 16 movies, so it is worthwhile to consider its plot and technique. It is an easy book to criticize; it is exceptionally uneven and often drags. It could have used a good editor. Nonetheless, taken on its own terms, it’s a great tale. The first four chapters are generally considered the best. The form of the book is a series of journals, meticulously kept by all the principal characters except the Count: this accounts for the variation in quality. And if a journal won’t do, there are newspaper clippings. In any case Jonathan Marker, the real estate agent who goes to Transylvania to handle the transportation for resettling Dracula and the other Nosferatu (the undead), writes his account of traveling to the castle of Dracula and the strange goings on there, f^e is concerned, for example, that the Count is never around in the daytime, but we know why. In exploring the castle to find a way to escape, he comes across Dracula in his earth box:

He looking much younger. The cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby-red underneath: the mouth was redder than ever, for on the lips were gouts of fresh blood, which trickled from the corners of the mouth and ran over the chin and neck . . . It seemed as if the whole awful creature was simply gorged with blood; he lay like a filthy leach, exhausted with his repletion.

Harker was unsuccessful in stopping the movement of the Count and undead associates to London, with its teeming millions, where a vampire would be happy as a pig in mud. From Harker’s journal we pick up the story in the journal of the young women who are soon to become victims of the vampire, and Dr. Seward. the superintendent of an insane asylum. He recruits his old professor. Dr. Van Helsing, to deal with the puzzling strange pallor that comes over Lucy Westenra shortly after the ship bearing the Count’s earth boxes reaches port in England with the entire crew dead. In Mina Harker’s diary we witness this scene of Lucy sleepwalking in a churchyard:

When I got almost to the top I could see file seat and the white figure, for I was now close enough to distinguish if even through the spells of shadow. There was something long and black, bending over the half-reclining white figure . . . I called in fright. “Lucy. Lucy” and something raised a head, and from where I was I could see a white face and red, gleaming eyes.

Once Van Helsing arrives on the scene, he is agonizingly slow in recognizing the problem. He puzzles it out, very slowly, on his fingers. Finally he produces quantities of wolf bane, crucifixes and garlic—all in a vain effort to save Lucy’s life. Poor Lucy! Like the Count she has obtained “available immortality” (Wolf’s phrase), but the good Victorians won’t let her off with that. They are, by golly, going to save her soul. Some saving! Her fiancé is instructed by Van Helsing to drive a wooden stake through her heart, which is more complicated than, say, hanging a painting, “The Thing in the coffin writhed; and a hideous blood curdling screech came from the opened red lips.” But now the grisly task was done. “There, in the coffin, lay no longer the foul Thing that we had so dreaded . . . but Lucy as we had seen her in her life, with her face of unequalled sweetness and purity.”

No wonder, then, that once this crowd of Christians began to get hot on his scent, Dracula retreats to Transylvania. Almost. Just before the sun sets on that ancient land, our heroes catch the wagon carrying his earth box and wrench it open with a great squealing of nails. One severs his head and another sticks a Bowie knife into his heart:

It was like a miracle: but before our very eyes, and almost in a drawing of breath, the whole body crumbled into dust and passed from our sight. I shall be glad as long as I live that even in the moment of final dissolution, there was in the face a look of peace, such us I never could have imagined might have rested there.

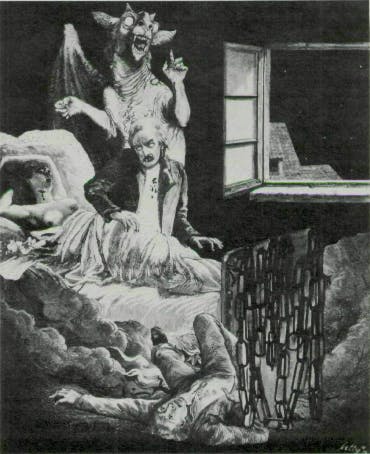

In places where the story sags, one can be satisfied by the many pictures and the annotations. Little is required to inspire an annotation. For example, on the first page Harker mentions he had a Hungarian chicken dish, and on page two there is a recipe for paprika chicken. Also, footnote 16 in the first chapter gives us the different races and their numbers inhabiting Transylvania in 1888. Footnote 22 discusses the problems of hair growing in the palm of the hand and the curious description of the Count as compared to an 1857 account of the baleful physical characteristics that overtake one caught up in the evils of masturbation. There is a note on page 193 about the shapes and sizes of stakes suitable for driving through the heart of a vampire.

Dracula is often equated with the basic evil forces in the world, the Antichrist, Darkness. Historic fact and folk legend have combined to preserve the vampire idea, still as fresh as today’s blood. One sympathizes with the evil Count, who worked out a grand lifestyle that went heavily for solitude and old ruined houses, and we admire his ability to survive over the centuries. Our heroes were convinced that given the choice, Dracula would too, like Lucy, prefer that his soul be released from its filthy prison, and, as already mentioned, there was allegedly a peaceful look on his face at the moment of his dissolution. Yet, considering Dracula’s heroic efforts to avoid capture, one can only assume that given his druthers, he would have gone on as before. Today he would have taken his case to the ACLU.

If Dracula is indeed gone, the legend will remain. As we all seek escape from the everyday horrors of modern life, we cling to those pleasant, imagined horrors with relief, as a way to blot out reminders of our own weakness and mortality. The Annotated Dracula is a fun book to have around, and can be read on

whatever level one’s imagination seeks

on a given terrifying evening.