On a cool Monday morning in July 2015, Afranio Solano strolled through a farmer’s market in Bogotá’s main plaza, a square surrounded by the Colombian Congress, the Constitutional Court, the mayor’s office, and the city’s largest Catholic cathedral. Peasants offered fresh yellow potatoes, oval rings of garlic, or a few clusters of bananas. Solano, a mestizo who stands five and a half feet tall, blended in easily, greeting people with calloused hands and a wide smile. He spoke with a low tone of voice, as if imparting a secret. As Solano chatted with some farmers, his two government-supplied bodyguards surveyed the crowd suspiciously. They don’t like him to linger too long in any one place. After a few minutes, one asked Solano to move on. Even though he was wearing a bulletproof vest under his thick blue jacket, he wasn’t safe. “I have to just keep walking,” he told me.

Solano can’t afford to be careless. Whoever assassinates this 50-year-old activist can claim a $26,500 bounty offered by the Urabeños, a right-wing paramilitary group. In 2015, 105 activists and human rights leaders were murdered. At least 21 have been killed so far this year, including seven land claimants like Solano.

Solano moved to Bogotá in 2011 after the Urabeños threatened him. Today he is one of Colombia’s nearly six million forcibly displaced people—the second-highest such number in the world, after Syria. Most displaced people, or desplazados, have moved to vast shantytowns in the main cities of Colombia. They were forced to abandon their homes and livelihoods as paramilitary groups, guerrilla fighters, and the military fought for control over their land. Very few desplazados try to return to their homes. Solano is not even considering it. “No way, not if I want to remain alive,” he told me.

The home he left behind is in Urabá, a region near the Panama border. It is swarming with armed groups. Although the police and the military have a presence in Urabá, the government cannot control all the groups trading drugs, weapons, or people. The strongest organizations in Urabá right now are the left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Urabeños.

Some desplazados fear they no longer have anything to return to. Others are reluctant to revisit the place where they were forced to witness massacres, sexual violence, or torture. Still others can’t return because cattle ranchers or agro-industrial companies have taken over their lands. In the case of Solano and his family, paramilitary groups that were financed by cattle ranchers and banana corporations, like the U.S. multinational Chiquita Brands, seized their land in 1998.

The land question has been at the heart of Colombia’s civil war. Guerrilla groups claim they took arms in 1964 to protect the interests of peasants; paramilitary groups have defended the agro-industrial model over the claims of small property owners; and the army claims it can’t control who has power over Colombia’s land, despite receiving plenty of military aid from the United States. Drug dealers also use the land for coca production and manufacturing cocaine. The issue has taken on new urgency as the government closes in on a peace agreement with the FARC. In 2012, President Juan Manuel Santos approved a law that promised to eventually give land back to desplazados. In 2013, the government also committed to land reform if a peace agreement is reached in 2016.

Both sides agree the peace agreement is now in its final stages. The expectations are high, but so is the fear. In the mid-1980s, a few left-wing groups created a political party, the Patriotic Union, that adopted the FARC’s ideals. State and paramilitary forces killed roughly 3,000 party members, at least 457 of them in Afranio Solano’s home department of Antioquia. A chief concern now is that paramilitary forces, like the Urabeños who threatened Solano, will target activists and demobilized FARC guerrillas.

Colombia is at a fork in the road. The country can finally address the causes that triggered a 50-year civil war, and end it once and for all. Or it could squander that opportunity, if it allows people like Afranio Solano to be murdered.

Born to a family of peasants, Solano was the oldest of five children. His father cultivated plantain, yucca, and avocados on the family’s small plot in Urabá. His father bought the land in the 1970s for 7,000 pesos (around $146 today)—still a considerable amount of money for a family of peasants. In addition, his father knitted hammocks, wove baskets to collect rice, and made woven fans to fight Urabá’s Caribbean heat. “I learned everything from him,” said Solano. “We used to knit four or five baskets together a week, we would put all the corn in them, or rice or yucca.”

“We were all illiterate, we couldn’t afford any education by moving to the cities, and we knew little about the rule of law,” Solano added. When he was 13 he was approached by FARC guerrillas who wanted to recruit him. “I refused to join any armed group, like my father did,” Solano said. “I told them I wanted to grow up and make a decision, as if I was choosing a religion.” Solano laughed at the comparison, even if choosing sides in the Colombian conflict is often like choosing which God you pray to.

In 1994, right-wing paramilitaries—which started as government-backed groups charged with combating FARC and other insurgents, before becoming powerful illegal armies in their own right—arrived in the area. They first took over the villages, where they killed peasants suspected of sympathizing with the FARC. In 1997, they killed Solano’s brother in-law, who belonged to the Patriotic Union. They killed another brother-in-law, an evangelical pastor who worked hand-in-hand with activist peasants. Fearing they would be next, Solano’s father in 1998 sold the family’s land for a very cheap price to José Vicente Cantero, a cattle rancher accused of being an ally of the paramilitaries.

All of Solano’s neighbors abandoned their plots, including Benigno Gil. “He was my best friend,” Afranio said, “I met him when I was eleven years old.” Gil started a social movement in 2006 called the National Board of Peasant Labor in the Recovery Land Program. He led a group of 400 desplazados who tried to forcibly reoccupy land in Urabá. Gil received threatening text messages telling him to stop land occupations in an area called Macondo, but he refused. Like Solano, he believed the only way peasants could get land back was by occupying it.

On November 22, 2008, a masked man in a motorcycle stepped in front of Gil’s vehicle, took a revolver out of its holster, and shot him three times. He died immediately.

Afranio Solano is now representing the peasants Gil used to represent. Paramilitaries have threatened him for organizing peasant squatters in Macondo and the larger Urabá region. According to Solano, they said: “We will kill you and your family. The only land you’re going to see is the one at the cemetery.” Solano refused to leave Urabá at first, but he kept a low profile, meeting secretly with other activists, lawyers, and peasants.

Solano also cultivated an unusual “spy” within the ranks of the paramilitaries: his cousin, who had joined the Urabeños. He was the first member of Solano’s family to join an armed group, and two more family members subsequently joined him. “They were all forced to do it because they were unemployed,” Solano said.

It’s not uncommon in Urabá to know the faces of the men who are in armed groups: many times they are neighbors, childhood friends, even family members. Solano told me the overlap can bleed into the absurd: In 2010, the Urabeños kidnapped Solano’s oldest daughter, who is in her twenties, but she was able to escape a month later with the help of a middle school friend who was a guard where she was being held hostage. “He woke her up at one in the morning one night, took her to the mountain, and put her on a boat by the Rio Cauca. She eventually got to a small village and was able to call me,” Solano said. He considered turning himself in to the paramilitaries, but a friend stopped him.

The paramilitaries offered Solano’s cousin one million pesos a month, which is around $335 today. His job is to be el politico—the politician—the person who picks the hitman in charge of killing a target. One day paramilitary commanders ordered the cousin to pick the hitman who would kill Afranio Solano. “He could not warn me directly or otherwise he would get in trouble,” Solano said. “So he asked his brother to warn me that the day of my death was approaching.” That’s when Solano quickly packed his bags and left his Caribbean home to hide in the Andean foothills of Bogotá. He cannot go back to Urabá. The paramilitaries placed a hitman in front of his mother’s house, in case he dares return.

Flying into Apartadó, Urabá’s largest town, all one sees are bananas. The banana trees are perfectly aligned, one behind the other, their fruit ready to be exported to markets in the United States and Europe. It is a disconcerting sight. Bananas are what cotton was to African-Americans in the American South, or sugar was to former slaves in the Caribbean. They are a symbol of violence and war.

Big blue bags hang from the trees. They are designed to protect banana clusters from mosquitoes and other pests, and to create a microclimate that allows the bananas to grow faster. Between the trees, hundreds of crisscrossed yellow nylon ropes are arranged to prevent the clusters from touching each other—from touching anything at all, really. If a leaf or branch touches a banana cluster, the bananas could develop minor brown spots, which are considered “defects.” Such bananas are not exported but sold in Colombia’s internal market. They are called el rechazo, the rejects.

Solano told me the tension over Urabá’s land is concentrated in two areas: California and Macondo. Macondo is where Benigno Gil and Solano led peasant squatters pressing their land claims against cattle ranchers and banana businessmen. California is a large banana field owned by the Echeverris, one of the richest families in the region.

The Echeverris started producing bananas for the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands) at the beginning of the twentieth century. The company left after the army committed a massacre against thousands of its striking workers in 1928, but returned decades later and was, until recently, a major player in the country’s banana industry.

My guide to the California banana field was John Pérez, a stern 46-year-old man who always wears a jean hat. He used to live in California, where he cultivated plantain. His old plot is now covered in bananas. Pérez was waiting for the state’s new Land Restitution Unit to give him back his land. “We occupied this land 29 or 28 years ago,” he told me.

The road we were driving on gave Pérez the chills. In the early 2000s, he would see dozens of cadavers on the sides of the road. They were banana workers, killed because paramilitaries insisted they were allied with the guerrillas, who had infiltrated the banana unions in the 1980s and 1990s.

We had arranged to meet Plinio Calabres, Pérez’s father-in-law, a tall, thin man in a red shirt with gray hair and a gray mustache. He is the only peasant in California who was able to remain when paramilitaries displaced the other families. His house is now completely surrounded by banana trees.

“We used to be a very closed community,” Plinio’s wife told me, while offering me a glass of water. It was the middle of the day, the temperature reaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit outside Plinio’s house. “We were a nice community, we didn’t need anyone else,” Plinio added. “I could just give something to my compadre, and he would give something to me. You know what I mean?”

Mosquitos were everywhere. The surrounding banana trees raised the level of humidity in the house. At one point Plinio suddenly slapped my left arm, then laughed, explaining that he was killing a mosquito about to bite me. Over several hours, mosquitos constantly bombarded our arms, legs, and necks. “Sometimes, when planes fumigate these plantations around us, I get some of the pesticide on my arms and my head, and it burns my skin,” Plinio said, touching his long, skinny arms.

The California field once belonged to a businessman, Raul Hasbún. The state expropriated the field at the end of the ‘90s, since Hasbún was not cultivating anything on it. Then Hasbún joined the paramilitaries and became one of the most powerful commanders in the region. The banana companies feared the guerrillas who had infiltrated the banana worker’s unions, so they paid paramilitaries for “protection.” This sometimes resulted in indiscriminate killings of banana workers—the bodies left on Urabá’s paved road like so many rejected bananas.

“Every company paid me three cents per banana box exported, every month, so I was collecting 400 million pesos per month ($200,000),” Hasbún said in 2011, from a high-security prison six hours away from Urabá. He was sentenced to 20 years in jail for murdering banana workers and left-wing activists.

John Pérez didn’t recall ever seeing Hasbún, but he did see many armed paramilitaries. “One day, a man came to our house saying he was representing the true owner of our land,” John said. The man’s name was Felipe Echeverri. He told John and the other families that, if they wanted to stay in California, they would have to pay Hasbún four million pesos ($2,000) per hectare—a fortune for families making $5 a week selling plantains and fruits. In return, Echeverri said they would own the land. (This was a lie, since the state owned it.)

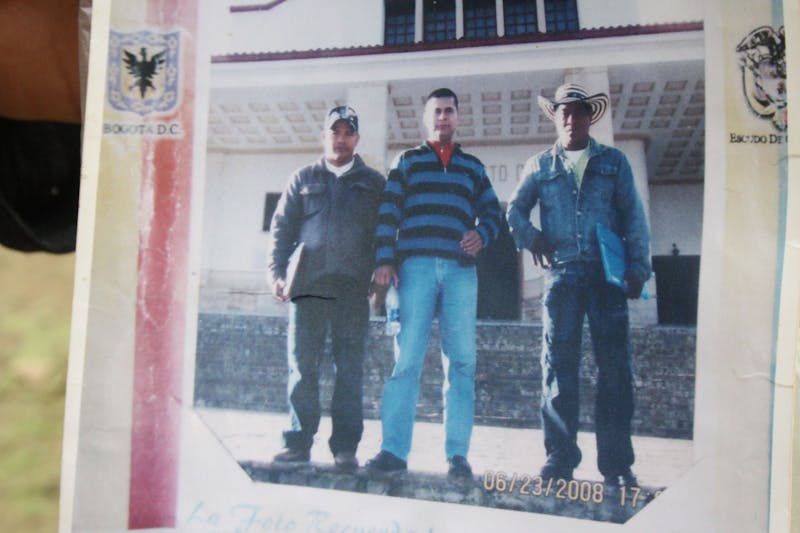

John remembers the meeting well. Six representatives of the families went to meet in in an area called La Teca, and Echeverri was waiting for them, flanked by two paramilitary commanders. “There was a table separating us from them,” John said. “And they put guns on the table, revolvers. I couldn’t pay the money they were asking me to. So I had to leave. And I left, with my wife and two kids, to figure out what to do somewhere else.”

Plinio, on the other hand, somehow managed to pay the $5,000 demanded of him. “I had never paid that amount of money to anyone, in my life,” he said. “I have never gained a lot of money to do groceries, or to buy rum. How can someone be so miserable to ask for that much money to a poor person?” Plinio said he sold all the plantain he had cultivated, leaving his three children and wife without much to eat for a while. They depended on the closest church charity to get some rice and coffee to survive.

The heat was unbearable as we sat on the porch of Plinio’s wooden blue house. He opened a beer and sat in a rocking chair. His thin 60-year-old wife sat next to him in a plastic chair. They looked out over the fields of banana trees, where plantain used to grow.

“Sometimes I wonder if our hearts are made of stone,” Plinio said.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because we put up with all this. We saw all of this change just like that.”

A few days later I met Echeverri at his lawyer’s office in Apartadó. The air-conditioned office was freezing cold. Echeverri, 46, looks like an MBA student: He shook my hand firmly, and greeted me with a beaming smile. His straight brown hair was raked to the right side, and he was wearing a pressed blue shirt. He was born in Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city, and goes to Urabá to check his plantations once or twice a month.

Echeverri is the youngest of a Colombian banana elite. His grandfather, Arcesio Echeverri, worked for the United Fruit Company in the 1920s. He was first a railroad driver, then a banana producer who left Colombia for Honduras after the 1928 massacre. Felipe’s father, Diócesis Echeverri, grew up and worked for Chiquita Brands in Honduras until a plague destroyed many of the Central American banana fields in the 1960s. The United Fruit Company decided to relocate to Colombia, in Urabá. “Our patrimony has over 50 years,” Echeverri told me.

Echeverri and his mother, Rosalba Zapata, have produced bananas in Urabá for Chiquita Brands, Dole, and Del Monte. He said most of the bananas he produces go to England, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States. He complained that the land restitution claims made against him by peasant activists like John Pérez, Plinio Calabres, and Afranio Solano have ruined his good name. “Banks don’t want to take my money any more, I have to carry all my cash with me,” he said. He wouldn’t name the banks, but insisted that they don’t want to take his money because he has been accused of supporting paramilitary groups and displacing peasants. “My reputation is bad,” he said, “because of all the lies they’ve told about me.”

Like many businessmen, Echeverri criticized the land restitution law and the new peace process. He thinks the government is blindly supporting peasants. The Land Restitution Law forces businessmen like Echeverri to provide a lot of evidence proving they bought the land without fraud and in “good faith”—meaning, they did not take advantage of peasants cowed by violence. This provision is meant to shift the burden of the proof from the displaced peasant to the business owner.

Cattle ranchers and banana producers both think that legal “shift” should be considered unconstitutional, but Human Rights Watch called it a “historic opportunity to restore millions of acres of land to Colombians who have been driven from their homes by violence.” In 2012, the banana producer guild of Urabá opposed a march of peasants supporting the land restitution law.

Echeverri argued that the new peace process was flawed because the interests of the guerrillas will dominate. The guerrilla fighter he had in mind is Gerardo Vega. Vega, who refused to be interviewed, is an activist lawyer who used to be a member of the People’s Liberation Army (EPL). The EPL demobilized in 1991 under an amnesty law, but the fact that a former left-wing combatant is now helping landless peasants makes their claims very suspicious in a businessman’s eyes. “Gerardo was part of the conflict and didn’t spent a single day in jail,” Echeverri said.

Vega is also a friend of Afranio Solano and of the landless peasants claiming the California field. Regarding the California case, Echeverri admitted he charged peasants like Plinio and John money. But he also said there was no revolvers involved in the negotiation.

“I was just representing a friend, Raul Hasbún. I had no idea then that he was a paramilitary commander,” Echeverri told me, while applying a mobile fan to his face, despite the cold air coming out of the air conditioner. “To me Hasbún was just a friend that I grew up with. I have no idea what all of my friends do, people do a lot of businesses here and there, and there are many things about your friends you don’t know. Do you know what all of your friends are doing? I can not be blamed for the crimes my friends committed.”

Echeverri’s claims are hard to believe. Claiming ignorance of the fact that his lifelong friend was leading the deadliest paramilitary army in Urabá in the 2000s is to ignore an elephant in a very tiny room. Hasbún said in 2011 that everybody knew who he was, which presumably included Chiquita Brands and people like Echeverri. Chiquita is currently facing a lawsuit in Florida over Hasbún’s accusations; the company claims it did not give the payments voluntarily, but was extorted. It does admit paying $1.7 million to the paramilitaries from 1997 to 2004.

Echeverri insisted that his family has been investing in “this country for many years,” that they are well-respected, and that they should not be subjected to this land-claim drama. How this drama plays out will say a lot about where the Colombian government comes down in the long conflict between generations of banana businessmen and landless peasants in Urabá.

“This is a time bomb, I am telling you,” Echeverri told me.

On a cold Tuesday morning in January, I visited Afranio Solano’s house in Bogotá. The two-story red building where he lives is located in El Galán, a working-class neighborhood named after a liberal presidential candidate who was murdered in 1989, allegedly by Colombia’s famous drug lord Pablo Escobar. It’s not known as a dangerous neighborhood, but Solano’s two bodyguards have to check the entrance at all times from the two corners of the narrow street where his home is located.

Solano spends most of his time in his tiny one-bedroom apartment, which he shares with his three daughters and wife. From there he makes phone calls to Urabá and the lawyers helping his land-reclamation efforts. “It’s like living in a cage,” he said. “I can’t even leave the house to buy bread, I spend most of my time at home.”

Sometimes Solano has so little money that his wife, a fruit vendor, must pay the rent for him. She is is also from Urabá, a survivor of one of the worst massacres in the region, at a village called El Tomate, where paramilitaries killed 16 peasants and burned several houses. They killed her grandparents and two uncles. She left to the nearest city and never came back.

“I haven’t worked in a year,” Solano told me. “I don’t have a degree, so it’s hard for me to get any jobs in this city. I used to have a way to support my family in Urabá, but this is what violence does to you, it just takes everything away from you.”

It is also hard to get a job in Bogotá, he said, because no company wants to hire someone who has two government-supplied bodyguards. “They think immediately they are going to get in some kind of trouble if they hire me,” he said. Without a job, he does his activism work for free.

In 2011, he and a friend managed to collect enough money to travel for three weeks to Paris, Berlin, and Strasbourg. Their plan: demand that the European Union stop buying bananas from Colombia until the companies there decide to fund a reparation plan for all desplazados. “It was a complete failure,” Solano said, almost laughing at his fiasco. No one seemed to be interested in what they had to say about Urabá.

In Bogotá, he has continued to receive death threats. “In 2014 I got the worse ones,” he said. He showed me a sheet of white paper that was sent one night to the NGO office where he sometimes volunteers. It read: “You and your shitty family will be dead.” A second one said: “You will get your land, but a lot of land above you AFRANIO SOLANO, we are waiting for you for our victory.” He carefully organizes all the threatening letters, emails, and text messages in a brown folder, as if they were birth certificates or tax information.

The only crops Afranio Solano owns now are two green tomato plants tucked into the corner of his apartment. “This is my field now,” he joked. But he has an ideal field in his mind. “Last night,” he said, “I dreamt I bought 60 pods of cacao to cultivate them.”

The Fund for Investigative Journalism supported research for this article.