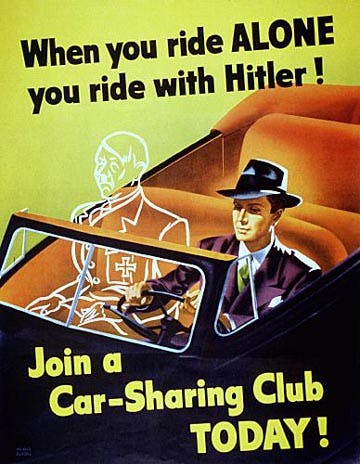

On December 7, 1941, Japan’s surprise attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor killed more than 2,000 people and drew the country into World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the War Production Board to oversee the mobilization, as factories that once produced civilian goods began churning out tanks, warplanes, ships, and armaments. Food, gasoline, even shoes were rationed, and the production of cars, vacuum cleaners, radios, and sewing machines was halted (the steel, rubber, and glass were needed for the war industries). Similar mobilizations occurred in England and the Soviet Union.

Today, some environmentalists want to see a similarly massive effort in response to a different type of existential threat: climate change.

These proponents of climate mobilization call for the federal government to use its power to reduce carbon emissions to zero as soon as possible, an economic shift no less substantial and disruptive than during WWII. New coal-fired power plants would be banned, and many existing ones shut down; offshore drilling and fracking might also cease. Meat and livestock production would be drastically reduced. Cars and airplane factories would instead produce solar panels, wind turbines, and other renewable energy equipment. Americans who insisted on driving and flying would face steeper taxes.

Though climate mobilization has existed as a concept for as many as 50 years, it’s only now entering the mainstream. Green group The Climate Mobilization pushed the idea during a protest at the April 22 signing of the Paris Agreement. On April 27, Senators Barbara Boxer and Richard Durbin introduced a bill that would allow the Treasury to sell $200 million each year in climate change bonds modeled after WWII War Bonds. Bernie Sanders has mentioned mobilization on the campaign trail and in a debate. And Hillary Clinton’s campaign announced last week that if she’s elected, she plans to install a “Climate Map Room” in the White House inspired by the war map room used by Roosevelt during World War II.

Despite these inroads, climate mobilization remains a fringe idea. Its supporters don’t entirely agree on the answers to key questions, such as: What will trigger this mobilization—a catastrophic event or global alliance?

Who will lead this global effort? When will the mobilization start? And perhaps

the greatest hurdle isn’t logistical or technical, but psychological:

convincing enough people that climate change is a greater threat to our way of

life than even the Axis powers were.

Lester Brown, environmentalist and founder of the Earth Policy Institute and Worldwatch Institute, says he first introduced climate mobilization in the late 1960s. His approach is holistic—and ambitious. “Mobilizing to save civilization means restructuring the economy, restoring its natural systems, eradicating poverty, stabilizing population and climate, and, above all, restoring hope,” he wrote in his 2008 book, Plan B 3.0.

Brown proposes carbon and gas taxes, and pricing goods to account for their carbon and health costs. In his “great mobilization,” all electricity would come from renewable energy. Plant-based diets would replace meat-centric ones. According to Brown, this new economy would be much more labor-intensive, employing droves of people in services like renewable energy and in compulsory youth and voluntary senior service corps. Brown also advises the creation of a Department of Global Security, which would divert funds from the U.S. defense budget and offer development assistance to “failed states,” (he cites countries such as Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Iraq) where climate change’s impact on available natural resources will exacerbate political instability.

This may sound far-fetched, but Brown believes we’re at a tipping point for climate mobilization. The economy is increasingly favoring renewables over fossil fuels, and grassroots campaigns like the Divestment Movement are gaining steam. Any number of circumstances could push the globe over the edge toward mobilization: severe droughts that create conflicts over water, or the accumulation of climate catastrophes from raging fires to hurricanes. When we cross over, Brown told me, “suddenly everything starts to move. ... We’re just going to be surprised at how fast this transition goes.”

For environmentalists who’ve seized upon Brown’s idea, the transition has not been fast enough. They’ve tailored their plans to include more explicit links to the war effort and a new sense of urgency. In 2009, Paul Gilding, the former executive director of Greenpeace International and a member of the Climate Mobilization’s advisory board, and Norwegian climate strategist Jorgen Randers published an article outlining “The One Degree War Plan.” The authors set out a three-phase, 100-year proposal for healing the planet, beginning with a five-year “Climate War.”

In that first phase, a cadre of powerful countries—the United States, China, and the European Union, for example—would act first, forming a “Coalition of the Cooling” that would eventually pull the rest of the globe along with them. Governments would launch the mobilization and reduce emissions by at least 50 percent. One thousand coal plants would close. A wind or solar plant would blossom in every town. Carbon would be buried deep in the soil through carbon sequestration. Rooftops and other slanting surfaces would be painted white to increase reflectivity and avoid heat absorption from the sun, which makes buildings and entire cities more energy-intensive to cool. Later, a Climate War Command would distribute funds, impose tariffs, and make sure global strategy is “harmonized.” According to the paper, this Climate War should start as early as 2018.

Much has changed since the release of Brown’s Plan B 3.0. Months after Gilding and Randers published “The One Degree War Plan,” climate negotiators faced the crushing defeat of the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, where delegates left without toothy commitments. The world has experienced one record-breaking temperature after another, and two of the three global coral bleachings on record. Last year’s climate conference in Paris was a relative success, as an unprecedented number of countries proposed plans to cut their emissions. And although the final agreement won’t bind countries legally, the consent to meetings every five years to consider ramping up commitments and the efforts of groups like the “high ambition coalition,” which pushed for a legally binding agreement, showed progress. But even before the ink dried, environmentalists and some politicians condemned the wishy-washy language and limp goals.

Leaving the fate of the planet up to such diplomacy has “always been a delusion—one that I had, by the way,” says Gilding.

“In that diplomatic world they have a notion of political realism which is quite separate from physical reality,” says Philip Sutton, a member of The Climate Mobilization’s advisory board and a strategist for an Australian group advocating a full transition to a sustainable economy. “The physical reality is now catching up with us.”

To compare the fight against climate change to WWII may sound hyperbolic to some, but framing it in such stark, dramatic terms could help awaken the public to that “physical reality”—and appeal to Americans less inclined to worry about the environment.

“It’s not tree hugging—it’s muscular, it’s patriotic,” said Margaret Klein Salamon, director and co-founder of The Climate Mobilization. “We’re calling on America to lead the world and to be heroic and courageous like we once were.”

When Salamon began working on the group that would become the Climate Mobilization, she was earning her PhD in clinical psychology. “I view it as a psychological issue. What we need to do is achieve the mentality that the United States achieved the day after the Pearl Harbor attacks,” Salamon said. “Before that there had been just rampant denial and isolationism.”

Indeed, climate denial is still pervasive. Only 73 percent of registered U.S. voters believe global warming is even occurring according to the most recent survey. Only 56 percent think climate change is caused mostly by human activity. It’s going to take a catastrophe much worse than Hurricane Katrina or Sandy to alter public opinion to the degree necessary for a climate mobilization—and even then, achieving that war mentality may be impossible.

“We’re good at fighting wars. … We fight wars on drugs and wars on poverty and wars on terrorism,” says David Orr, a professor of environmental studies and politics at Oberlin College. “That becomes kind of the standard metaphor or analogy for action.” But climate change is “more like solving a quadratic equation. We have to get a lot of things right.”

There are other reasons the war analogy doesn’t hold up. WWII mobilization was prompted by a sudden, immediate threat and was expected to have a limited time span, whereas the threat of climate change has been increasing for years and stretches in front of us forever. But perhaps the biggest difference is that our enemies in WWII were clear and easy to demonize. There is no Hitler or Mussolini of climate change, and those responsible for it are not foreign powers on distant shores. As Orr says, “We’ve met the enemy and he is us.”