We’ve reached the beginning of May, and no candidate has won the outright majority of delegates needed to claim their party’s presidential nomination. But whether each party has a “presumptive nominee” is a matter for some debate.

Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump certainly seem to think the matter is settled. After winning four of five primaries on April 26, Clinton took the stage and delivered a victory speech that looked ahead to the general election. Trump was even more emphatic after his sweep of the I-95 primary, bluntly declaring, “I consider myself the presumptive nominee.” Some talking heads and party operatives have also started to use the term. But many media outlets have been slow to the draw.

The press is tasked with a crucial role in the democratic process: informing the public honestly and objectively of the state of the race. As such, it matters when journalists make the subtle yet meaningful switch from “frontrunner” to “presumptive nominee.” And this year’s standards for declaring a candidate “presumptive” are different than those of years past.

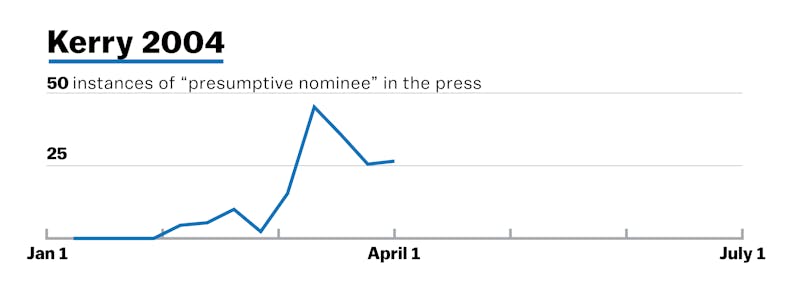

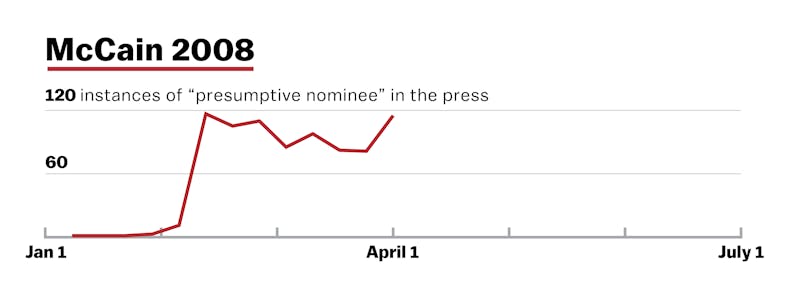

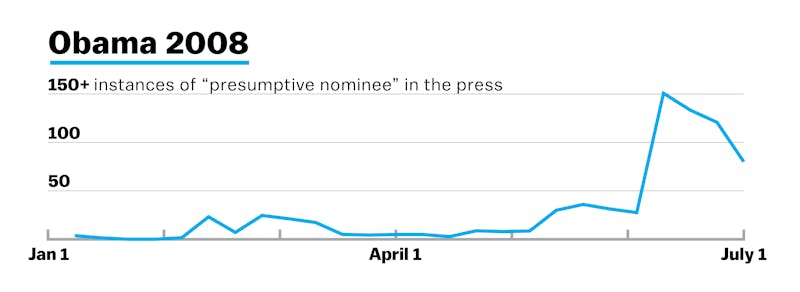

I used the research service LexisNexis to search newspaper archives from 2004, 2008, and 2012 for the term “presumptive nominee” or “presumptive [party] nominee” within 30 words of the eventual nominee’s last name. The results are not all that surprising: In every primary race, there comes a tipping point where it is clear that a winner has emerged. But, as the year-by-year results show, how that point is decided upon can vary wildly.

In 2004, John Kerry became the clear frontrunner after defeating initial favorite Howard Dean in Iowa on January 19 and in New Hampshire on January 27. But media outlets almost universally abstained from calling him the presumptive nominee until March 3. The previous day, Kerry had dominated the Super Tuesday states, his last serious rival (John Edwards) had dropped out, and President George W. Bush had called to congratulate him on sewing up the nomination. From that point on, he was the media’s unquestioned presumptive Democratic nominee, although it did not become a mathematical certainty until March 11.

In the 2008 Republican primary, outlets also began dubbing John McCain the presumptive nominee after Super Tuesday, February 5—a prolific election day when 21 states voted and McCain won the majority of available delegates. Mitt Romney, who had emerged as the main alternative to McCain, dropped out shortly after. However, McCain still had a ways to go until he reached a delegate majority, and Mike Huckabee continued to contest the nomination.

For the next month, the race hung in a kind of no-man’s land: McCain did not yet have the raw numbers to mathematically clinch, but his overwhelming lead and Huckabee’s limited, sectional appeal made it plain to political observers that McCain was the inevitable nominee. References to him as the presumptive nominee spiked after February 12 and February 19, two primary nights when McCain did well and tightened his grip on the party’s nod. Finally, on March 4, McCain clinched a majority of convention delegates, and Huckabee dropped out, allowing the final holdouts in the media to use the p-word.

The Democratic primary, of course, was a much more drawn-out affair: Neither Barack Obama nor Hillary Clinton came close to the nomination until May. (A small flurry of stories mentioning a “presumptive nominee” in February were leakage from coverage of McCain’s coronation.) Slowly over the course of May, it became clear that Clinton needed a nearly impossible proportion of the remaining delegates to catch Obama. On May 10, Obama passed an important threshold: swaying more superdelegates to his side than Clinton. After the Oregon primary on May 20, he clinched a majority of pledged delegates. That made some publications comfortable enough to name him the presumptive nominee, but most continued to defer to a defiant Clinton. Finally, on June 3, the day of the final primaries, Obama surpassed the magic number of total delegates, opening the floodgates for the “presumptive nominee” epithet. Clinton conceded the race on June 7.

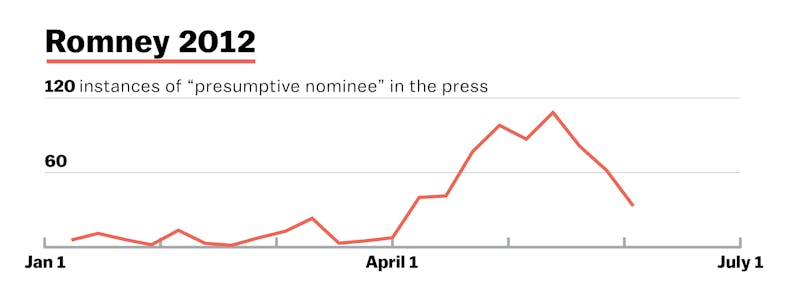

Finally, in 2012, it took Mitt Romney until April to assume the mantle of presumptive nominee. After dispatching Rick Santorum in the Wisconsin primary on April 3, news outlets began to tiptoe up to the big declaration with sentences like, “Republican Mitt Romney has notched a huge presidential primary triple win, strengthening an already compelling case that he is the presumptive nominee.” On April 10, Santorum dropped out, and references to Romney as the presumptive nominee skyrocketed.

However, as with McCain four years earlier, a more stubborn rival—Newt Gingrich—lingered, and Romney remained short of a delegate majority. Then, on April 25 came an unusual intercession by the RNC: Reince Priebus himself announced that Romney’s “strong performance and delegate count at this stage of the primary process has made him our party’s presumptive nominee.” Reports immediately surfaced that Gingrich would soon drop out, and from then on the press safely considered Romney the presumptive nominee, despite the fact that he would not mathematically clinch the nod until May 29.

Generally, it appears that a candidate is considered his party’s presumptive nominee when his last serious challenger drops out or he mathematically clinches—whichever comes first. But there is still room for interpretation. As Romney’s 2012 experience suggests, is there a point where the collective cognoscenti will declare the race over before either of those two conditions are met? In 2008, why was Romney considered McCain’s last serious challenger, and not Huckabee? Did Kerry earn the “presumptive” label because Edwards dropped out, or did Edwards drop out because Kerry had earned the “presumptive” label?

This cycle’s data helps shed light on this chicken-or-egg problem. On the Democratic side, one can make a strong case that Clinton is more of a presumptive nominee than past “presumptive nominees” were. By The New York Times’s latest count, Clinton has 2,183 of the 2,383 delegates (92 percent, a figure that includes superdelegates) she needs to clinch the Democratic nomination; McCain in 2008 and Romney in 2012 were both considered presumptive with only about 60 percent of the necessary delegates. Furthermore, Bernie Sanders faces the tall order of needing to win 83 percent of remaining Democratic delegates. Clinton supporters would certainly argue that the math means Sanders is no longer a “serious challenger”; in other words, he has gone from a Santorum to a Gingrich. Yet the media is so far declining to call the match despite Sanders’s increasing unviability.

Although Clinton has clearly passed one test to qualify as “presumptive,” our experience in previous cycles suggests the media will continue to shy away from that label until there is an unambiguous knockout blow: Clinton clinches a delegate majority or Sanders drops out. Of course, Clinton herself once benefited from this phenomenon—in 2008, a primary season that the press appears to be using as a template for 2016. Coverage of the Obama-Clinton race of 2008 suggests that a drawn-out, two-person race where neither candidate drops out will only be settled by cold, hard math.

On one hand, the media is justified in refraining from making a sudden rhetorical shift when Clinton has locked up the nomination in such a gradual way as to be imperceptible. But on the other, the Democratic race clearly stands in a very different place than it did in February, when Sanders still had a realistic path to the nomination. Calling her the “presumptive nominee” at this point would be both honest and consistent with past use of the term.

The Republican primary is its own beast—a once-in-a-generation unsolved mystery that cannot be compared to 2004, 2008, or 2012. With Ted Cruz and John Kasich mathematically eliminated but vowing to fight on, the only unknown left is whether Trump will reach the magic number of 1,237 delegates before the Republican National Convention. If so, he will, of course, have earned the title of presumptive nominee. But if not, for the first time in decades, the Republican Party will skip the “presumptive” step entirely. With a nominee chosen on the spot on the convention floor, one lucky Republican could go straight from hopeful to officially nominated candidate.