What can children’s books tell us about America’s prisons? Karen Rivers’s new book, The Girl in the Well Is Me, offers one set of answers. The book is recommended for readers in grades five to eight—in other words, the period when a child is reaching the cusp of young adulthood. To say that adulthood contains any more trauma or heartbreak or violence than childhood would be indulging in a simplistic view of childhood itself. But what adulthood and its literature does allow for is a more nuanced understanding of these subjects: how those we love can be the same people who hurt us, how guilt can consume us when we have done nothing wrong, and how our lives are often shaped by events far beyond our control. The Girl in the Well Is Me explores all these topics, and does so through a subject that children desperately need their authors to take on: what it is like to be the child of an incarcerated parent.

The Girl in the Well Is Me opens with its eleven-year-old heroine, Kammie, falling into a well—the result of an initiation held by her new school’s resident mean girls. Kammie has just moved to a grim crossroads she calls Nowheresville, Texas, after her family suddenly left their home in New Jersey. It will be a long time before she tells the reader exactly why. All we know, at the beginning, is that Kammie has gone from a cossetted middle-class life of concerts, skating lessons, and trips to Disney Land, to one in which her mother works two back-breaking jobs and spends all her time either asleep or in tears. Kammie is desperate to start over in a new school where no one knows who she is or how she ended up in Nowheresville, and sees a friendship with the popular girls as her big chance. It’s no surprise that they aren’t much help to her when she falls into a well, and finds herself trapped. “Kandy Proctor is not the kind of girl who falls into wells,” Kammie notes grimly, as one of the popular girls peers down at her.

“We’ve been talking and we’ve decided that…well, just get out of there,” another of the popular girls instructs her. To those who do not struggle with the problems faced by children with parents in prison, life can seem this simple: You’re in a tight spot, so get yourself out of it. It’s easy to think you can get out of the well if you’ve never found yourself deep inside it. But Kammie knows better, and, by the end of her story, so do we.

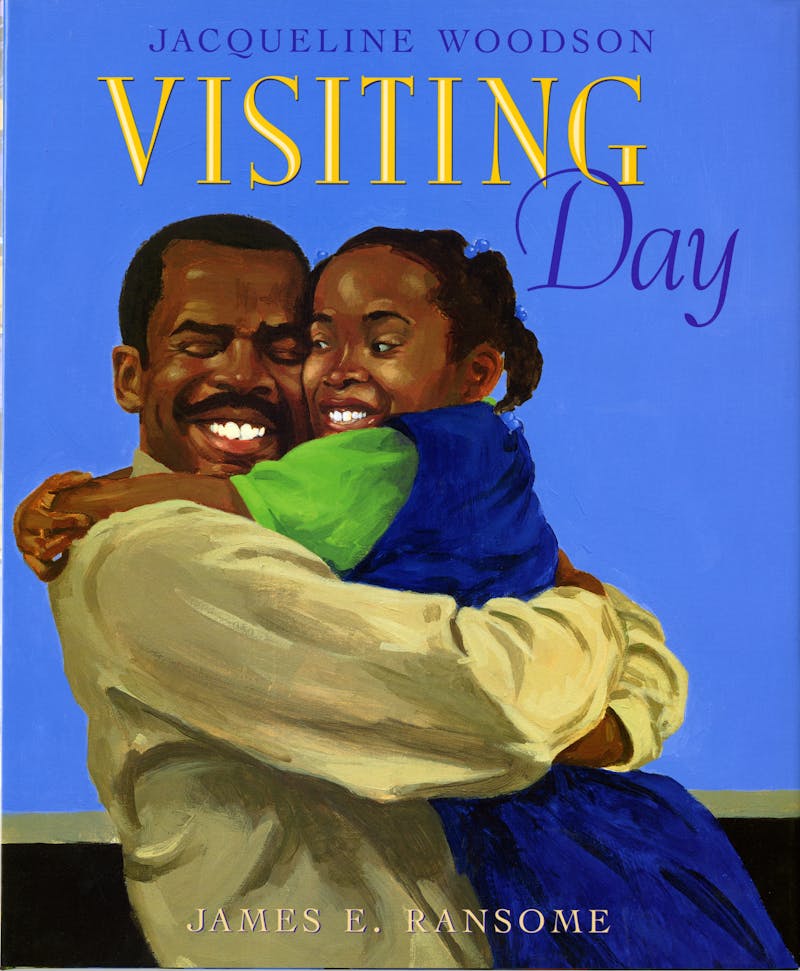

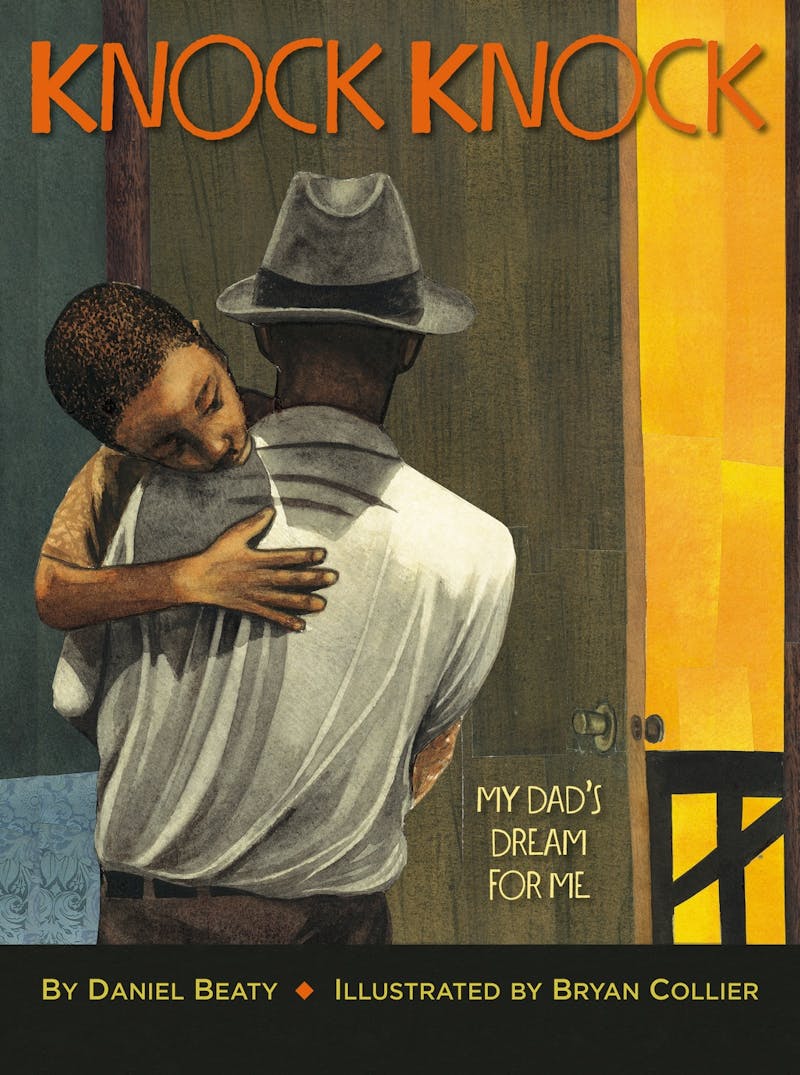

According to the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated, over 2.7 million American children—or 1 in 28—has a parent in prison. This figure skyrockets among black children: In this population, one out of every nine children has an incarcerated parent, compared to less than 2 percent of white children. In this sense, The Girl in the Well’s Kammie, a white child from an affluent background, is an outlier. But two widely acclaimed picture books—Daniel Beaty and Bryan Collier’s Knock Knock and Jacqueline Woodson and James E. Ransome’s Visiting Day—address their stories to the children statistically most likely to lose a parent to incarceration.

Both Visiting Day and Knock Knock, which won a 2014 Coretta Scott King Award, depict black families torn apart by a father’s incarceration, but their similarities end there. In Visiting Day we see a family that still sees itself as a family, and a daughter who counts down the days until her father comes home. In Knock Knock, circumstances are more mysterious—just as they would be for a young child.

The boy at the center of Knock Knock begins the book by telling us of a game he and his father share: Every morning his father knocks on his bedroom door, and he pretends to be asleep until his father is beside his bed. Then he “jump[s] into his arms.” But one morning, the boy’s father isn’t there. The boy doesn’t know why, and we are left to guess the reason, and to read the boy’s letters to his absent father. “Papa, come home,” he writes, “‘cause I want to be just like you, but I’m forgetting who you are.”

After a long time, the boy’s father writes back. “No longer will I be there to knock on your door,” he tells his son, “so you must learn to knock for yourself. Knock knock down the doors that I could not… Knock knock for me, for as long as you become your best, the best of me still lives in you.” The book ends with father and son reunited, but only after the boy we saw at the beginning of the book has grown into a man.

Knock Knock began its life not as a children’s book but as a monologue, inspired by author Daniel Beaty’s own experience of his father’s incarceration, which began when Beaty was three years old. Visiting Day is a similarly personal story for its author, Jacqueline Woodson, and its illustrator, James E. Ransome. Ransome had previously kept the “family secret” of his brother’s incarceration, and Woodson grew up visiting her favorite uncle in prison. “I never knew what his crime was,” she wrote in an author’s note to Visiting Day,

and it really didn’t matter. I knew I loved him dearly and he loved me with the same ferocity… As he laughed and talked with me and my family, I forgot, for the moment, where we were. I knew we were a family. I knew were happy. I knew there was lots of love in the room.

Visiting Day is true to Ransome’s memories of her own visits with her uncle. In its opening pages, a girl wakes up early and joyfully anticipates the monthly trip she and her grandmother will take to see her father in prison. “And maybe Daddy is already up,” she tells us, “brushing his teeth, combing his hair back, saying, ‘Yeah, that pretty little girl of mine is coming today,’ with all the men around him looking on jealous-like ‘cause they wish they had a little girl of their own coming.” We never learn what crime the girl’s father has been convicted of, and the same is true in Knock Knock: These stories are not about crime, but about family.

Ransome’s illustrations for Visiting Day are filled with warm, bright colors, and depict the prison’s visiting room as a space filled with men laughing and embracing their children. These are images that can help children see prisons as places where love can survive, but there are some aspects of incarceration that even the brightest colors cannot change.

The book ends, as it must, with the girl leaving the prison with her grandmother, and leaving her father behind. But the two remain focused on the future, and on their knowledge that they are still a family. “Grandma says all it takes is time,” the girl tells us, “and while we’re holding out waiting for Daddy to come home we can count our blessings and love each other up and…make big plans for when Daddy comes home again.”

The most powerful message Visiting Day bears for any child who turns to it is that a family’s love can endure even under the most traumatic of circumstances. The most probing question it poses to the adult reader is whether families should have to endure such pain.

The struggle of growing up with a parent in prison is a story children’s literature is just beginning to tell. Writing of his work on Visiting Day, illustrator James E. Ransome remarked that he “questioned whether or not we should shed light on such a controversial issue.” Visiting Day was published in 2002, and it’s difficult to say whether, in the intervening decade, Americans have grow more willing to talk about the needless suffering mass incarceration inflicts on both inmates and their families—or whether America’s prison population has simply grown so staggering that we finally recognize we cannot put off this conversation any longer.

According to the ACLU, America’s prison population increased 408 percent between 1978 and 2014. 1 in 110 adults is currently incarcerated. Astounding as these figures are, we can still find a way to ignore them if we can convince ourselves that they depict only those who deserve to be locked away, only those who have forfeited their rights as citizens—only the guilty. Yet even those of us who reject the idea that American courts are capable of convicting innocent defendants cannot ignore the pain and confusion that millions of children endure when their parents are suddenly taken from them, often for reasons they cannot understand.

Children’s books depicting parental incarceration may still be catching up with an issue most Americans are reluctant to talk about, but it still seems to be moving faster than adult literature. Visiting Day is not alone: Since its publication, it has been joined by titles like Mama Loves Me from Away, An Inmate’s Daughter, and When Dad Was Away. Only if books like these continue to flourish, however, can authors hope to speak not just to an experience shared by countless American children, but to the way these children’s experiences diverge. It can happen to your father, to your mother, to your stepparent; your family can stick together or fall apart. It can happen to your neighbor. It can happen to your best friend. It can happen to you.

This universality might be the greatest strength The Girl in the Well Is Me has to offer. Before the protagonist, Kammie, is a kid with a dad in prison, she’s a kid just like nearly any white, middle-class reader, who loves horses and skating and playing video games with her brother. Only after a young reader has come to identify Kammie does she tell them about a part of her life the reader may not identify with—but one they can learn to identify with through Kammie’s story.

The reader spends almost the entirety of The Girl in the Well Is Me down in the well with Kammie. By the end of the book, the girl in the well is us. In the process, we do little more than listen in on Kammie’s thoughts as she slowly reveals the circumstances that led her there. It’s a bold move for a children’s novel to take: A reader has to feel compelled to keep turning pages not because the heroine is being chased through a dystopian obstacle course, but because she is making her way through the equally terrifying landscape of her own mind.

Author Karen Rivers falls a little too deeply, at times, into the adult trap of trying distractingly hard to sound like a relatable preteen. (“I made my smile look real by crinkling my eye corners,” she recalls. “‘Smize,’ like that woman on TV always says.”) But the book’s most powerful moments are its simplest, the ones that take place outside of time and place and pop culture, when Kammie is allowed to show that a child’s experience of losing a loved one to prison is just as complicated and painful as an adult’s. Near the end of the book, after she has told the story of her father’s arrest and imprisonment for embezzling, her family’s sudden move, and how the loss of all that was familiar to her made her feel that she was losing not just her surroundings but her sense of self, Kammie also tells of a moment when she contemplated suicide:

I opened the door of the medicine cabinet, and inside there were about ten bottles of pills… I took out the cotton balls and sniffed them. I like the way cotton balls smell, OK? Also the way they feel against your skin, like rabbits and something gentle. On the side of the sink was a mug with a happy face on it… I put some water in the mug and drank it and wondered if any of those pills would make me un-be.

The Girl in the Well Is Me ends with Kammie’s rescue, but more importantly, it ends with Kammie rescuing herself from her desire to un-be. There are still no easy happy endings: Her father is still in prison, and she is still working through her feelings of betrayal and anger. By the end of the book, the reader knows that Kammie’s greatest pain comes from the fact that she feels utterly isolated by her struggle. But books like Knock Knock, Visiting Day, and The Girl in the Well Is Me have the power to reassure millions of children that they are not alone. For young readers who are not coping with losing a parent to incarceration, these books can provide something just as meaningful. They can help them grow into adults who see America’s inmates as human beings.