There is something amiss when journalists openly cross-examine a President of the United States about his attendance record and work habits, Normally such topics are rightly regarded as trivial, the kind of personality-profile fluff that would earn a serious political reporter the scorn of his peers. Yet at his most recent news conference Ronald Reagan was not only asked such questions but forced to answer them. Is he “running things”? Is he “a full-time President”? That such questions are being asked suggests there are some big pieces still missing in the Reagan puzzle. By the fourth year of a Presidency we are supposed to be examining the quality of an incumbent’s performance, not whether he shows up for work.

Yet the reporters are on to something. In circling around what is beginning to be called the “leadership issue,” they are closing in on what in fact has been one of Reagan’s greatest political strengths: his well-practiced detachment from anything unpleasant—including government itself. He is an incumbent President who refuses to act incumbent. He plays chief of state grandly but often abdicates his coincidental role as head of government. Faced with complexity, he refers the matter to “experts” or commissions. Faced with failure, he dissociates himself. Lebanon is only the most recent example.

Reagan’s uncanny ability to step away from the responsibility for the conduct of “the office I now hold,” as he called it in his reelection announcement speech, has often been attributed to the fact that he is an actor. Of course he can escape accountability—didn’t he spend years slipping from one costume into another? Isn’t he trained to move from one scene to another, from one role to another? No wonder he speaks so convincingly, even when the lines have been hastily rewritten—isn’t that what an actor is paid to do? If times are tough, he can be cheerful. If critics are mean, he can be amiable. If his programs cannot sell themselves, he can apply the magic of the storyteller, the spell of the fantasist.

Yet the actor explanation does not quite satisfy. Reagan, after all, is always Reagan. Unlike other actors, he is a man not of a thousand faces but only of one (or at most two). There have been other actors-turned-politician, but none who pulled off such a dazzling entrance into politics and such shining durability. What tends to be forgotten—what has never been fully recognized—is that Ronald Reagan earned his greatest fame not on the movie screen but on the television tube. People got to know Ronald Reagan, the man, not at their neighborhood theaters but in their own living rooms. By the millions they met him not as an actor but as something subtly but profoundly different—as a television personality. Rather than see him playing someone else, they grew used to him in a far more intimate role, that of himself: your host, Ronald Reagan.

During his eight years on the old General Electric Theater, Reagan enjoyed certain distinct professional advantages. While the program’s other performers were at the mercy of the weekly dramatic material—it was an anthology series—the star was not. He was no more responsible for the quality of the shows than for the quality of G.E.’s products. As the “host,” he occupied a more defensible position. It was Reagan who ended each show with the famous slogan, “Here at General Electric, progress is our most important product.” That “here” was located at some imaginary point between General Electric itself and your living room. But unlike more recent TV pitchmen, such as Lee lacocca and Frank Perdue, Reagan was never burdened with the pretense that he was himself part of the actual production. He never purported to know anything about building cars, plucking chickens, or designing light bulbs. On the contrary, our host was someone like us—a typical consumer of the sponsor’s products. My strongest memory of G.E. Theater—twenty-five years later—is the image of the host and his wife, Nancy, sitting side by side in the spacious Uving room of their “totally electric home.” They looked a bit better off, perhaps, than most of their audience—and they were not embarrassed by the luxury—but they did not seem in any important way different from us. In fact, they personified what we wanted to be, or, to put it a bit more commercially, what we wanted to have.

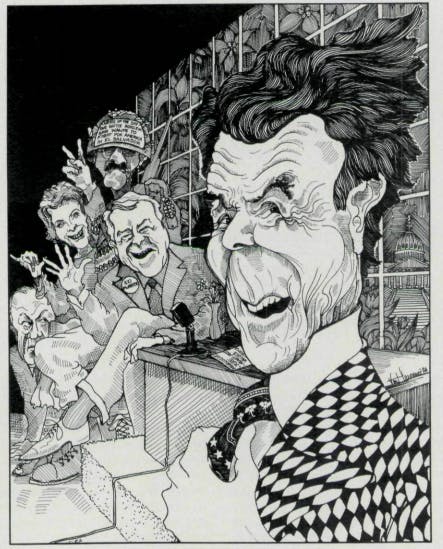

The persona of host was crucial for Reagan in the transition from actor to politician, and as President he has worked hard to perfect that persona, which did so much for him in the golden 1950s. Consider, for example, how he works his Presidential press conferences. For Reagan, the reporters seated before him row on row in the East Room serve an important function. They are the means by which he shows the audience at home what a regular guy he is. No President has ever worked harder to demonstrate this quality. Did you ever wonder how it is that this President is so good at names in his press conferences? No matter who the reporter, no matter how obscure the news organization, the President always seems to know the particular “Joe” or “Bob” or “Ann” on a cozy, chummy, faintly paternalistic first-name basis. And if Reagan appears in full control—not of his material but of the White House press corps itself—it is no accident. He has done his homework. First, he uses a seating chart. Second, before coming on camera himself he checks a closed-circuit television monitor of the press room, and he scans the various Joes, Bobs, and Anns. With the aid of this hidden monitor, he is able to get a fix on the location of those reporters with whom he intends to be intimate that evening. Having matched nicknames with faces, and faces with seats, Reagan is ready to go on the air. He is the host of the show, the reporters are his guests—and he is ready to impress the public with his kindly geniality (and ready, in the process, to provoke war whoops in newsrooms across the land as each publisher or editor in turn hears the President of the United States call on his correspondent in Washington by his first name.)

All of this is about as spontaneous as the decision to air these broadcasts in primetime. When we see the President in one of these debonair performances, we see not a head of government confronting a potentially hostile press but a quizmaster on familiar terms with his contestants. Sometimes the show does not run as smoothly as it should. In Reagan’s last outing there was a bit of confusion when he called the name “Pat.” The target, Patrick McGrath of Metromedia, told me later that at first he couldn’t believe this friendly diminutive was addressed to him. He had no reason to assume the President knew his name, especially since he was quite clearly looking past him to the row behind. Still, after a beat he stood and asked his question, What else was he supposed to do, live on all three networks?

During one of these evening programs, on July 26, 1983, the President carried his role as host to its logical conclusion. Before taking questions, he announced that he was going to introduce “three new members of the White House press corps”—welcoming them, as it were, to the White House press conference family. As the smiling President called the names of these members of the Washington press establishment, it was difficult not to think of Johnny Carson introducing Ed, or of Richard Dawson introducing a set of new contestants on “Family Feud,” or even Jimmy Dodd introducing a brand-new Mouseketeer.

Reagan does his best work as national host on his Saturday radio addresses. The content of these broadcasts recalls one of his memorable one-liners from the 1980 campaign. “I’ll admit I’m irresponsible,” he would say, challenging the holders of official power, “when they admit they’re responsible.” Each week, as he schmoozes with us over the airwaves, he purrs the same message: they are the ones responsible. No matter what is ailing the country at the time, those who tune in at 12:05 P.M. Eastern Standard Time hear the same off-stage “they” being called on the carpet. Each Saturday that Iowa trained radio voice comes to us bristling with complaints about government—that dread purveyor of deficits, crime, irreligion in schools, and other evils. Listening to him, it is easy to forget that this Paul Harvey-on-thePotomac is in real life the head of the federal Administration.

The subtext of every radio speech, its hidden message, is the same: Reagan is not in government, he exists at some unique point—previously uncharted—?J(?- tween us and government. As a disembodied voice on the radio—the White House refuses to allow the broadcast sessions to be televised—he becomes a kind of national neighbor, concerned, just as we all are, about the way things are going. The timing of the broadcasts reinforces the subtext: it’s not a regular work day, so even more than usual the President is off duty, removed like us from the Washington power structure. It was from this ambiguous position that he described the shabby treatment given his good friend Jim Watt. Free to ignore the immediate cause of Watt’s departure, the famous reference to “a black, a woman, two Jews, and a cripple,” our host rounded up the usual suspects—the media, the far-out environmentalists—and bemoaned the injustice done his friend. Tuning in, one would never have guessed that this indignant but apparently uninvolved commentator was actually the same man who had quite briskly accepted Watt’s resignation.

Reagan has proved equally adept at hosting the State of the Union. In these annual addresses he has polished the role of host to a high sheen. Let the Bill Moyers types extol the President’s role as national educator; Reagan is not about to play schoolmarm on the intricacies of world events and fiscal policy. If, as in 1982, there was fear of unemployment, Reagan would talk soothingly of some quickly forgotten bauble, such as the New Federalism. If, as in 1984, there was anxiety about Lebanon, he would kiss it off in a single paragraph on the eighth page of a ten-page speech. The mass audience, he knew, would not study the transcript. But they would remember the mood.

To create the mood he seeks in his State of the Union addresses, Reagan has played the role of host not in some metaphorical sense, but literally and explicitly. Like Ed Sullivan on the old “Toast of the Town,” he livens up the proceedings by introducing celebrity guests seated in the studio audience. Last year it was Lenny Skutnik, the courageous Congressional employee who some weeks before had jumped into the icy Potomac to save a victim of the Air Florida crash. By introducing a real-life hero, and one whom the assembled members of Congress, Supreme Court Justices, and ambassadors could hardly decline to join him in applauding, the nation’s 16 THE NEW REPUBLIC host basked in the reflected glory of genuine personal courage. Reagan relished the moment enough to repeat it in this year’s address. This time the spotlight fell on Sergeant Stephen Trujillo, a hero of the Grenada operation. “Sergeant Trujillo,” the President said dramatically, “you and your fellow servicemen and women not only saved lives, you set a nation free. You inspire us as a force for freedom, not tyranny; for democracy, not despotism; and, yes, for peace, not conquest.” And then the kicker: “God bless you.” If you weren’t on your feet by then, you weren’t just unpatriotic, you were some kind of atheist besides.

As national host, Reagan has enviable political insulation. On the same evening that he focused the limelight on Sergeant Trujillo, he began shifting the responsibility for the coming debacle in Lebanon. Those who listened could hear the first unmistakable sign that the President was preparing to do exactly what he would savage others for suggesting: get the Marines out of Lebanon. That lone paragraph on page eight began with these words: “Your joint resolution on the multinational peacekeeping force...” Your—that wonderful second-person plural possessive—laid the blame right where Reagan wanted it, on the men and women sitting in the House chamber.

It was not the last time the President would fade himself out of the picture when the word “Lebanon” was mentioned. After withdrawing the Marines from their airport bunkers, where they had become as anachronistic as marooned Japanese soldiers still at their island posts, he again stood back. “Lebanon’s troubles,” he instructed a group of Republican women, “are just part of an overall problem in the Middle East.” REAGAN DENIES U.S. FAILED IN LEBANON, proclaimed the headline the next day. Asked at his last press conference a direct question— had the United States lost credibility in Lebanon, and had Syria won?—Reagan treated the audience at home to one of his patented narrations. Talking for eight full minutes, he produced an imaginative re-creation of events which had taken place at a distance. It was highly reminiscent of the Chicago baseball games he used to broadcast from a studio in Des Moines, thumping his hand on the table to simulate the crack of ball on bat. And if the home team is getting shellacked, why be the pitcher when you have the option of sitting on the sidelines and doing the play-byplay?

If Lebanon remains first on the Reagan Administration’s 1984 worry list, deficits are a close second. The man who promised to balance the budget “possibly by 1982” finds himself proposing a Si 80 billion deficit for fiscal year 1985. Here again, Reagan disclaims responsibility. Employing what Francis X. Clines of The New York Times describes as his “third-person impersonal mood of politicking,” the President warns (he is addressing Republican activists at Eureka College in Illinois that “politicians at the national level must no longer be permitted to mortgage our future.” Let members of Congress sit down, if they wish, with some of his staff people and see if they can come up with a “down payment” on the deficit. Would another President have felt obliged to propose a lower deficit in the first place? Never mind. It was a comfortable, and familiar, posture for Reagan to assume. Twice on the eve of the 1982 elections, Reagan had journeyed to Capitol Hill not to offer proposals for ending the deficits but to play guest host at rallies denouncing them; arriving at the Capitol steps, he presented himself not as the author of the federal MARCH 26, 1984 17 budget or even as a participant in the budget process, but simply as an average citizen, concerned, just like everybody else, about the rising tide of government red ink.

Every President, by virtue of his experience, brings with him a different notion of the office. Reagan, the Great Communicator, is no exception. As the host of a TV anthology series, Ronald Reagan learned that it was better for an actor not to be an actor and thus depend each week on the quality of the material. He learned that it was better for an actor to play himself-as-host, hovering gently oivr the material but never quite responsible for it. The key is detachment. (Four years ago Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter in the debate not by outscoring him but by brilliantly interposing himself between the audience and the event itself, by becoming not a contestant but a commentator. “There you go again,” he narrated^which was to say, “There you go again, you poor, desperate, grubby politician.”) Reagan, in his pre-political incarnation, played a ptirticular role in a large corporate structure. He was the spokesman for General Electric, not the C.E.O. Through all those seasons of pitching G.E. products and being charming, the audience at home never seriously held him accountable for the value or quality of those products. The public seems to view his role as spokesman for the products of the national government in a similar light. So far, no one has pried the lid off Reagan’s TV-age persona. If in fact he “does not apply himself,” as Walter Mondale charged recently, there is not yet any clear sign the public wants him to. It may be that the public is content with a President who skates easily on the surface of things. Still, I tune into each press conference waiting for that one courageous, self-effacing “Joe” or “Bob” or “Ann” to stand when called upon, look our national host in the eye, and ask the following question: “Mr. President, what is my last name?”