As a child, Blanche Wolf wanted more than anything to live a life surrounded by books. Born in 1894, and raised in Manhattan by well-to-do parents, her love of reading and culture set her apart from her family and their upwardly-mobile, secular, and socially-constrained Jewish community. When she met Alfred Knopf in 1911, she was attracted most of all to his bookishness—which, one suspects, he might have played up in order to win over the pretty redhead, underestimating how serious she was about it. Her dream life was simple, heartbreakingly so: “We decided we would get married and make books and publish them.” How could she have known that the hardest part of that dream was the “we”?

When the house of Knopf launched in 1915, publishing was a gentleman’s pursuit—amateur, clubbish, WASP, and above all, male. Blanche and Alfred navigated this casually anti-Semitic world, holding themselves aloof from their alcoholic, philandering competitor, the “pushy Jew” Horace Liveright, founder of the Modern Library and publisher of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Over the years there would be female secretaries, copywriters, reviewers, and editors at Knopf. There would be women in charge of little magazines and the children’s-book divisions of big publishers. But there would be no other woman in the publishing industry with the status of Blanche Knopf—either in the 1920s, when she signed Langston Hughes and Willa Cather, or in the 1950s, when she celebrated Albert Camus’s Nobel prize and oversaw the translation of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. And despite it all, although her husband swore he’d put her name on the masthead, he never did.

Alfred considered Blanche “much

more intuitive in her judgements” than he was, a description that condescendingly

implies a woman’s touch. Easier to believe it was instinct, rather than

intelligence, that allowed his wife to discern the quality of Harlem

Renaissance poets and hardboiled detective fiction, of French avant-garde playwrights

and political journalists alike. But he was happy enough to capitalize on the

quality she brought in. From the beginning, Alfred wanted the Knopf name to be

a marker of cachet; the Borzoi that became their company logo was a nod to the

Russian literature on which they built their reputation. As the company

treasurer Joe Lesser put it, “He wanted writers who considered Knopf superior

to other houses, pure and simple.” In her biography, Laura Claridge builds a

compelling case that it was Blanche, far more than Alfred, who was responsible

for that superiority, who pursued and persuaded writers to sign on—often for

low salaries and pitiful advances—for the sake of the firm’s reputation and for

her own devoted personal attention.

Yet despite Claridge’s determination to restore Blanche to the heart of the Knopf reputation, we don’t come away from the book with a strong sense of how she made her judgements—we don’t get to see her intelligence at work, or to read her commentary on new authors or her arguments in favor of one or another. Many writers came to Knopf through unofficial scouts—including journalist and satirist H.L. Mencken, and Carl Van Vechten, photographer, novelist, and white ambassador to the Harlem Renaissance. It was Van Vechten who squired Blanche to uptown jazz clubs, introducing her to Langston Hughes, acting as confidant and gossip, and opening her eyes to the rule-breaking, wife-swapping, and race-mixing that defined “modern” culture in 1920s New York. Claridge even borrows the label “tastemaker,” bestowed on Van Vechten by his recent biographer Edward White, for Blanche. (The book’s subtitle is “Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire.”) That slogan is a sign that Claridge hasn’t quite found the story in her biography, but pieces of several: the Knopfs’ fraught marriage and Blanche’s search for affection; her pursuit of talent and nurturing of authors; Knopf’s place in the publishing landscape; the pressures on the business from money and politics; the relationship between the American and European literary worlds. Threads of all of these narratives are picked up and dropped, but never quite woven together.

For the Knopfs, marriage proved much more difficult than publishing. In Claridge’s hands Alfred Knopf takes his place in twentieth-century literature’s crowded pantheon of assholes—his great loves were the American Southwest, expensive wine, and the ritual humiliations of his friends, his family, and most of all, his wife. One after another, acquaintances and co-workers attest to a relationship that today we’d call toxic; a stew of jealousy, incompatibility, violence, and—just when it couldn’t get worse—yearning affection. Their interests diverged so completely it was almost deliberate: “Everywhere she zigged, he zagged: she liked the East, he the West; she light meals, he stick-to-your-ribs food; she spirits, he fine wine.” Her taste in books was for poetry and fiction, his for history and music. Her apartment in midtown Manhattan was modern and decorated in her namesake white; he preferred the cavernous, gloomy country mansion in Purchase, in Westchester County just north of the city.

Then there was the extended family. Alfred’s father, Sam, muscled his way onto the company board early in the marital business experiment and did whatever he could to control where and how the couple lived. Alfred was dependent on his father’s good opinion and was desperate to emulate him, with “an affinity for salesmanship, a desire to be connected to affluent circles, and a taste for expensive travel, housing, dining, and tailoring.” It was a deep-rooted need: Alfred’s mother, threatened with divorce, had swallowed carbolic acid and died when the boy was just four years old. In an age of Freudian analysis, it was not difficult to find reasons for Alfred’s behavior, but that didn’t make it easier to live with.

The Knopfs’ one child, their son Pat, was born in the summer of 1918, and in a matter of weeks Blanche hurried back to the office, fearful that her father-in-law would push her out if she took too much time with her baby. The physical and emotional fallout of pregnancy and childbirth is oddly played down by Claridge, with the details of Blanche’s severe endometriosis and scarring from the resultant surgeries dropped into the middle of a paragraph with the note that these medical issues “made future pregnancies improbable,” although Blanche “preferred to think she was making the decision to have only one child.” Similarly, Claridge reveals that three years later, when the Knopfs were in England staying at the home of a publisher, Blanche took an overdose of pills “for reasons that remain undisclosed.” She hazards the theory that Blanche was still smarting in fury and “despair” over being written out of the firm’s public celebration of its five-year anniversary.

The challenge of biography is always to decide how, and how far, private life and public life feed and illuminate each other. Claridge’s biography of Blanche is restrained in this way, constructing a skeleton of facts rather than a spirit of interpretation. Often, those facts speak perfectly well for themselves: Deep in the throes of a wartime affair with a mysterious Frenchman named Hubert Hohe, Blanche decided to buy the apartment next door to her own and install a secret door. When Hohe, whom Blanche’s friends considered inferior and a con artist, broke up with her, the deliberately thin walls of the love nest tormented her as Hohe started loudly having sex with his new lovers.

Yet most facts are neither so salacious nor so telling, and the narrative is stuffed with names, dates, places, and trivia that don’t develop the contours of a story. A schedule packed with even the most illustrious names—dinner with Thomas Mann, lunch with Elizabeth Bowen, a party with Dashiell Hammett, and a meeting with James Baldwin—means little if there’s no space to let the personalities breathe, and the anecdotes merely slide along on a string.

Claridge has previously written biographies of Emily Post and Norman Rockwell, two cultural figures whose work offers an avenue into pop culture and the mores and values of a changing American landscape. But the yoking of life and culture here feels overly simple and too dismissive of the personal. Blanche’s intimate doubts and fears about motherhood—sharpened by her grandmother’s death in childbirth and by the suffering she endured for her endometriosis—are dragged into the public sphere and simplified to make a point: “The age itself seemed unsure. Margaret Sanger had recently dared to link contraception and women’s rights, arguing that women no longer had to become mothers: it was a matter of choice.”

Blanche’s dissatisfaction with her husband and her yearning for attention and connection from lovers is presented as though it’s merely au courant: “There was never a better time than the 1920s to be all over the sexual map. It sometimes appeared that romantic relationships everywhere were turning barmy.” Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, those reliable ciphers of Jazz Age excess, are pulled in as representatives of this “barmy” modernity and the fluid boundaries of marriage—but like Blanche and Alfred Knopf, the Fitzgeralds married young and never divorced, unable and unwilling to free themselves entirely from their bond. The psychological complexities that kept both couples together are impossible to know, but Claridge is oddly incurious about them.

For instance, after her son’s birth Blanche went on what Claridge calls mildly a “lifelong diet,” rooted in terror over gaining even ten extra pounds. She was already a chain smoker, and in the 1930s eagerly took DNP, a briefly legal diet drug that had been discovered as a byproduct of dynamite manufacture during World War I, which was “capable of literally cooking people to death internally.” It was banned in 1939, and may have contributed to her blindness in later life. Claridge observes that Blanche’s “desire to be her own woman” appears to demand, “paradoxically,” this obsessive dieting—she never calls it anorexia, although that doesn’t seem like a stretch. Yet it hardly seems paradoxical, rather painfully inevitable, that the price of personal freedom was this rigid control of her body.

The Knopfs’ son continued to be difficult, running away from home after he graduated his elite high school and failed to get into an Ivy League school. The parental competitive stakes were raised, Claridge writes, when Alfred, unbeknownst to Blanche, began procuring prostitutes for himself and his son, making the Purchase house more desirable than Blanche’s New York apartment. Once again, the much-vaunted Freudian awareness of the age doesn’t seem to have translated into better parenting.

During World War II, Blanche’s role as a powerful publishing figure was legitimized when she was invited to tour South America as cultural attaché, gathering information for the US government and helping with the effort to woo governments onto the side of the Allies. Those years proved pivotal, in which more was asked of her than before and she found herself able to rise to it. After publishing a book on Nazi war crimes by the U.S. prosecutor Robert S. Jackson, the Knopfs were asked to witness the Nuremberg trials; Blanche stayed, and Alfred returned to America, claiming he had “no stomach” for the horrors. Shortly after, she published the journalist John Hersey’s account of the Hiroshima bombings, and the postwar era seemed to promise Blanche a slate of new work that would truly matter as the world rebuilt itself. Through the 1950s, Blanche pursued James Baldwin and Simone de Beauvoir, celebrated Camus’s Nobel Prize, and Knopf enjoyed its most profitable year, in 1955, a triumph even in the shadow of McCarthyism and the death of the invaluable Mencken. (For all its high-mindedness, the books that kept Knopf afloat through the years were The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran’s collection of uplifting spiritual koans, Dashiell Hammett’s detective novels, and Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking—all brought in primarily by Blanche.)

When the Knopfs finally decided to sell the business to their old friends Donald Klopfer and Bennet Cerf of Random House in 1960, the fresh air blowing through the business showed how rank and vicious things had become. “Jesus, the way he talked to her,” Klopfer said. The new staff were “appalled” at the couple’s sniping and fighting in meetings, which the Knopf editors—like Blanche herself—had long come to accept as normal.

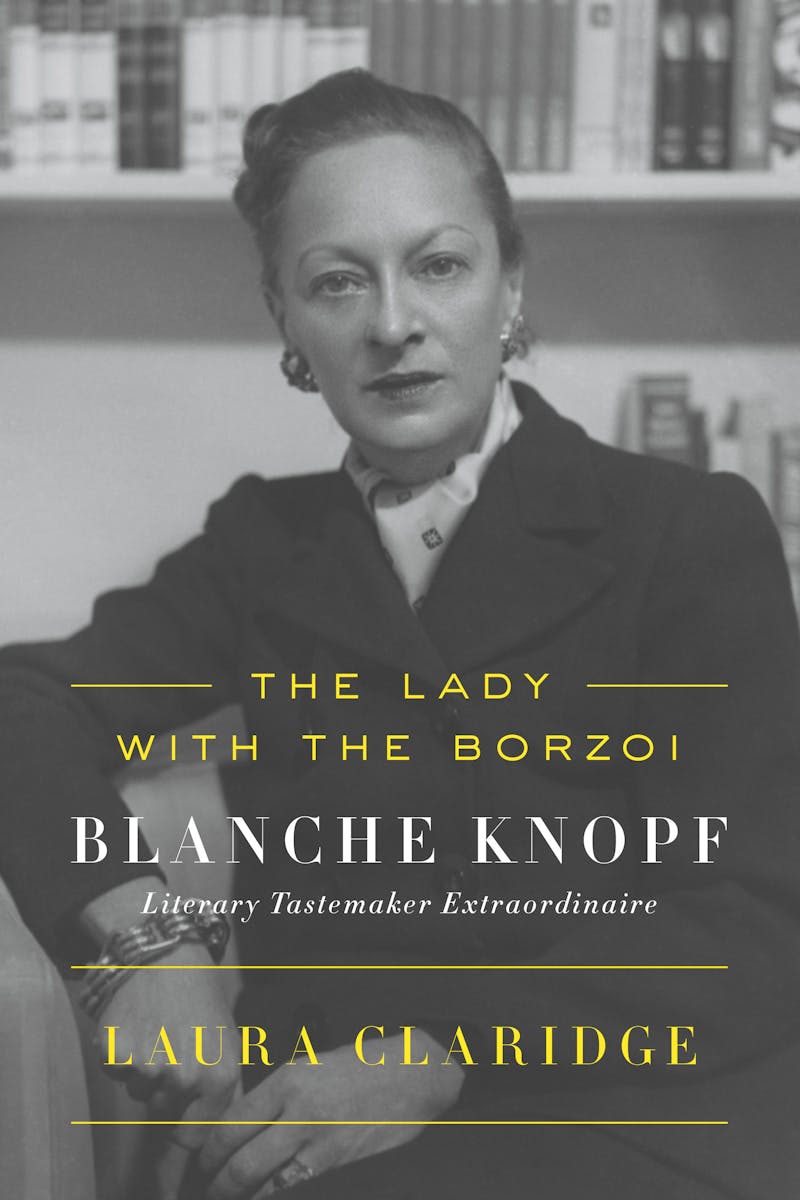

The photograph of Blanche on the cover of The Lady with the Borzoi shows a woman with plucked and penciled eyebrows arched over wide almond eyes, a steady gaze that slides just past the viewer, and no glimmer of a smile on her perfectly painted lips. Her eyesight, so essential to everything, deteriorated severely in her later life, so that she had to bend over manuscripts with a magnifying glass and clutch an assistant’s arm to cross the street. Blanche worked and traveled until the bitter end, physically wrecked, long after Alfred would have retired, and she was determined to appear healthy, to keep going, not to admit defeat and let him take the reins. This ought to be the beginning of her story, not the end.