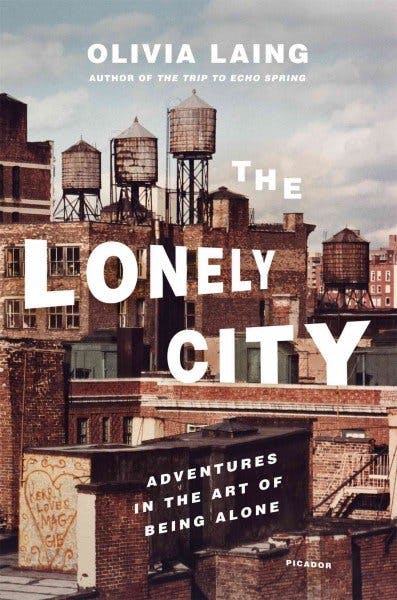

“I never went swimming in New York,” Olivia Laing remarks in an early chapter of The Lonely City, her meditation on urban solitude and artists who have illuminated its murky terrain. Laing is English, based in London, and during a period she spent living in New York several years ago—first in sublets in Brooklyn Heights and the East Village, later in a converted hotel in Times Square—she never stuck around for a summer, when the pools were open. When she was in town, alone and mildly despondent following the sudden end of a relationship, she wandered the far east side of Manhattan, where she took a special interest in an empty pool. “I was lonely at the time, lonely and adrift, and this spectral blue space, filling at its corners with blown brown leaves, never failed to tug my heart.”

As Laing reminds us, when we’re lonely, we see the world differently. We’re attuned to the apparently charmed lives of those around us, but also to other lonely people, as well as to sad movies, melancholy songs, and symbols of missed opportunity, such as empty swimming pools. (As Raymond Chandler quipped in The Long Goodbye, “nothing ever looks emptier than an empty swimming pool.”) Laing’s pool evokes that special blend of dejection, but it also recalls her previous book, The Trip to Echo Spring, a literary investigation into writers and alcoholism, which includes a consideration of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer.” There, a man makes his way home one evening through a suburban bedroom community via the backyard pools of his neighbors, stopping for nightcaps along the way. By the time he arrives, his house is empty, and life has passed him by. The story was published in The New Yorker in 1964, and by then, Cheever was well into his own solitary descent into drink.

Across all of her books, Laing is interested in how the baggage people carry threatens to define them, and how forces that are generally seen as destructive—alcoholism, radical loneliness—contain a kind of undeniable creative appeal. In Echo Spring, she juxtaposed close readings of Hemingway, Cheever, and Tennessee Williams’s lives and works alongside her own memories of growing up with a violent alcoholic (her mother’s partner, who lived with the family as a “friend” when homosexuality was not yet tolerated in England). In Lonely City, Laing again moves between memoir and criticism, focusing on the alienating effects of urban life as well as on those who find inspiration within its fragile ecosystems. In this, she poses the question of whether loneliness, usually seen as a form of failure, can be viewed as more complex, as something generative.

Laing is a literary critic, yet Lonely City draws primarily on visual

art, which speaks to her during her own dark period. As a new transplant to New

York, Edward Hopper’s chilly diner in Nighthawks

calls out to her from across the Met; Hitchcock’s Rear Window resonates with her own voyeuristic experience of living

alone in the city. On first glance, this seems like an unlikely turn: From

Baudelaire to Auster and Ferrante, there have been many fictional portraits of

loneliness, and more still when one includes the work of psychologists and

sociologists such as Freida Fromm-Reichmann, Robert Weiss, and David Reisman.

Laing nods at this scholarly literature, yet her central insight about

loneliness is that it is fundamentally visual, the thing that remains once human

connection has vanished and language rendered out of reach. In other words, when

we can’t speak, we must see. “When a person is lonely,” she writes, “they long to be witnessed,

accepted, desired, at the same time as becoming intensely wary of

exposure.” There’s an intimacy in being seen, and a kind of isolation when

we’re denied it.

The former books editor of the U.K. Observer, Laing has a gift for sifting through art and archival materials and finding sympathetic windows into her subjects, many of whom don’t typically benefit from such generous treatment. In her hands, close readings of works tend to illuminate biography, rather than the other way around: The frustrated intimacy of David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud series is contextualized by his diaries entries about cruising the Chelsea Piers; Nan Goldin’s 1986 exhibition, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, is complicated by shocking self-portraits of her own battered face. Lives and works are treated as texts, clues to broader psychological puzzles. Laing is a deft critic, and there’s an intimate, conversational quality to her approach—she’ll start with a memorable sentence or image, then drift almost anecdotally into a subject’s background, teasing out the implicit connections between loss and creation, the unsettling histories beneath the surface.

Laing’s critical compass is oriented by her fascination with outsiders, writers and artists whose iconoclasm often proved visionary. Lonely City includes a number of eclectic and excellently rendered mini-profiles of such people—Klaus Nomi and Vivian Maier, Sherry Turkle and Josh Harris—but the book focuses mainly on four main figures, starting with Edward Hopper, the painter whose images are “so resistant to entry, and so radiant with feeling.” Again, criticism emerges from memoir: Much of life in New York consists of being outside and looking in, and at the Met, her impressions about living privately in public crystallize when she overhears a docent observing that the chilly midcentury diner in Nighthawks is missing a door. What’s the significance of this? “Was the diner a refuge for the isolated… or did it serve to illustrate the disconnection that proliferates in cities?” Both, she determines: “The painting’s brilliance derived from its instability, its refusal to commit.” This gives way to a consideration of Hopper himself, who, painfully shy and withdrawn, discouraged his wife’s career as a painter at the advantage of his own, and created a cocoon around their unhappy relationship.

Like unhappy families, no two forms of loneliness are ever exactly the same. While the Hoppers were alone in their marriage, Andy Warhol saw himself as alone in a crowd. Burdened with the residual trauma of having grown up with a heavy Eastern European-inflected accent and a childhood stutter, he hid his reluctance to speak behind costumes and technology—namely a voice recorder, which he referred to as his wife. The device was central to the making of a, a novel, a book of transcribed conversations between the artist and Factory regulars. (Critics at the time decried a as parasitic and manipulative; Laing regards it as a “symbiotic exchange between… excess and paucity, expulsion and retention.”) Warhol’s book is tragic in many ways, but not because it fails at connection. In one of the most fascinating sections of Lonely City, Laing compares the artist’s ability to have his thoughts taken seriously with that of Valerie Solanas, radical feminist, writer, and Warhol’s would-be assassin. Solanas shot Warhol because she felt their fraught friendship was crowding out her own voice; after that, she pinged between mental hospitals and prisons before dying in a welfare hotel in San Francisco. While Warhol was canonized as a genius, Solanas drifted further and further into obscurity, eventually losing her ability to speak for herself, and assuming a place in history as a footnote to Warhol.

Wojnarowicz shared Warhol’s brand of aphasia, a struggle with speech that doubled as a kind of social paralysis. Like Warhol, Wojnarowicz was gay and had survived a difficult childhood. Unlike Warhol (or at least, unlike what popular mythology holds about him) Wojnarowicz was at ease sexually. While Warhol took comfort in policing the boundaries of intimacy—he would let people in then pull away from them—Wojnarowicz prowled the edges of Manhattan in search of fleeting encounters, rarely seeing the same man twice. His photography and journal entries captured these moments in vivid detail, rendering the Chelsea Piers as Blakean landscapes of pleasure and torment, inspiration for his work.

Henry Darger, the last main figure profiled in Lonely City, was the most removed from those who would later be considered his contemporaries, the most classically alone. A childhood orphan and lifelong bachelor, Darger lived all of his life in Chicago, where he worked as a janitor and spent his free time writing and illustrating an epic account of a Manichean battle between good and evil as led by a gang of young girls. The 15,145-page book, along with other prints and writings, were discovered after his death in 1973, and launched his reputation as an outsider artist. (The facts of his life and death no doubt facilitated his success, as they allowed Darger’s champions to interpret him without interference.)

Darger is frequently described as having suffered from an afflicted mind, yet Laing regards him as a victim of bad luck and negligent welfare systems; a man whose capacity for invention was inextricable from his ostracism. While Warhol, Hopper, and Wojnarowicz were lonely within vast networks of people and exchange, Darger had almost no close human contact. The Realms of the Unreal, with its vast scale and elaborate moral systems, is an effort not to document loneliness, but to populate it.

Is loneliness an aesthetic? The Lonely City seems to suggest that it is, that certain works speak in languages we can only understand when we’re in the proper frame of mind. On the one hand, this seems intuitively true—there’s something, say, about the songs of Elliot Smith or the blue paintings of Picasso that betray a sadness and longing that seems inextricable from their creators. In her own dark period, Laing gravitated towards figures who shared her outlook, and whose troubled histories came through in their art. Biography, of course, doesn’t determine interpretation, yet even if a viewer weren’t aware of Wojnarowicz’s childhood abuse or Darger’s reclusiveness, they would likely be able to intuit something haunted about their work. Loneliness may not be an aesthetic, but it is a mood, one characterized by a powerful desire for expression.

In the final pages of the book, Laing turns her attention to Strange Fruit (for David) a sculpture by the artist Zoe Leonard to honor the memory of Wojnarowicz. The work is made up of the skins of 302 pieces of fruit, which are dried and sewn together and left to rot and disintegrate on the floor of wherever they’re being shown. It’s a kind of mourning ritual, and in this, it suggests a new community, one forged in grief and rebirth. We may live alone and die alone, as Orson Welles once remarked, but in our loneliness, there’s company to be found.