In 1950, when Beverly Cleary published her first children’s book, Henry Huggins, Barbie had not yet been invented, let alone the touch-screen computer games that transfix children today. Charlotte’s Web wouldn’t come out for two more years, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone for nearly 50. But Cleary, who turns 100 on Tuesday, has remained so consistently popular through the decades, selling over 91 million copies of her 30-plus books, that new editions of her work are still being released with forewords from Amy Poehler and Judy Blume. When Cleary was on the Today Show earlier this month one girl—so young that she couldn’t even be called a millennial—told the hosts that Cleary’s books “inspired me to go out and read more.”

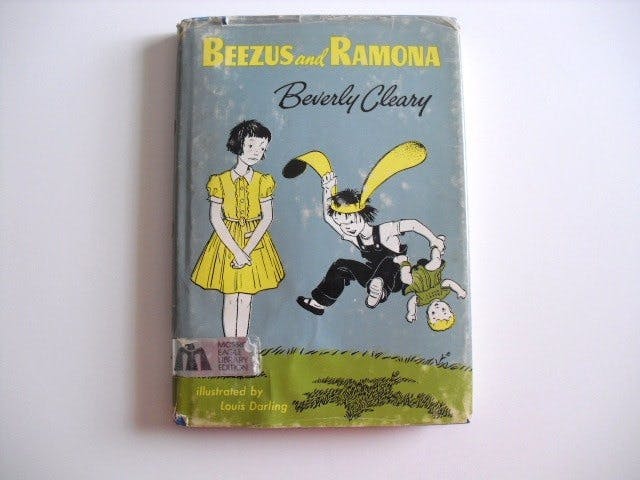

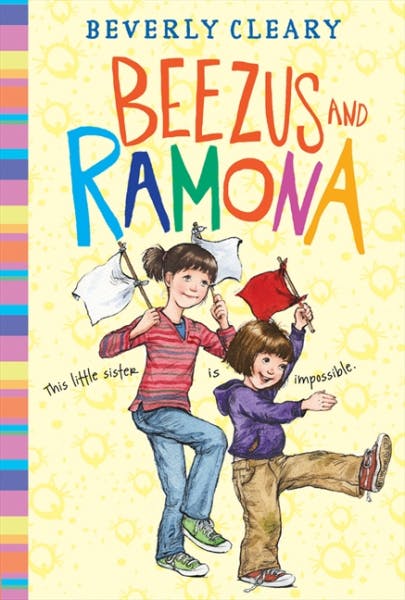

In some ways it’s odd that Cleary’s books have survived for so long. The majority of her books were written between 1950 and 1980, and her characters’ lives remain firmly rooted in the past, so much so that some parts read like historical fiction. Beezus, older sister to rascally Ramona, is first introduced while “embroidering a laughing teakettle on a pot holder,” while a major plot point in Ellen Tebbits involves woolen underwear, which now seems practically Victorian. As these details become increasingly outdated, publishers have tried to update her books with new illustrations to appeal to more modern children. In recent years Ramona’s bicycle and helmet have become decidedly contemporary, and the characters wear denim cutoffs instead of dresses.

Cleary’s enduring appeal is a

testament to her skill in speaking directly to children. At the core of each

whimsical vignette is a real childhood emotion. Who cares about the

technicalities of serving your dog horsemeat when what really matters is the fervent

desire to be loved by your kindergarten teacher or the unjustness

of seemingly arbitrary rules about mud inside the house?

Cleary’s is able to convey these emotions so vividly because she remembers her own feelings of childhood with uncanny accuracy, as she details in two memoirs, A Girl From Yamhill and My Own Two Feet. Written in the same simple and candid tone that make her children’s books so approachably delightful, these memoirs make clear that her appeal doesn’t have to be limited to children. A Girl from Yamhill follows Cleary’s childhood on a rural Oregon farm through high school in Portland, spanning her pioneer ancestors and her family’s struggles during the Depression. Her second memoir, My Own Two Feet, tracks her life from junior college in California, where girls knit in class instead of taking notes, through working as a librarian in World War II and publishing her first book.

It’s dangerous to draw parallels between a writer’s life and works, but for a grown-up Cleary fan, reading her memoirs is an exercise in spotting what autobiographical information has worked its way into Beezus and Ramona and her other hits. Young Beverly shares with Ramona the belief that the first bite of an apple tastes best, and, like Ellen, meticulously hides her woolen underwear from her classmates. Boys steal her home-ec cooking samples, as they do Jane’s in Fifteen, and she names her doll “Fordson-Lafayette” after a tractor, like Ramona’s “Chevrolet.” There are more serious parallels, as well: Cleary’s father’s struggles to find gainful employment during the Depression are clearly the source material for Ramona and Her Father, Cleary’s first Newbery Honor book.

Growing up, Cleary only had two picture books, Mother Goose and The Story of the Three Bears, and didn’t learn to read by herself until the second grade, which she blames on the mediocrity of the primers forced on children in school. Their contents could “scarcely be called” stories, she writes in A Girl In Yamhill. It’s easy to see her books as a reaction to this difficult early relationship with reading. Cleary understands that, unlike the characters in her school primers, children are not only concerned with “spinning tops, swinging high, and riding their stupid pretty ponies.” They are worried about the world around them, concerned that they are not feeling the right feelings, or that an adult will be able to see into their thoughts. This is why Beezus frets that she does not love Ramona enough, why Ramona hides behinds some trashcans when she sees a strange substitute teacher in her classroom, and why Ramona feels pure existential terror when she gets stuck in the mud and doesn’t know how to get out. The details of childhood tribulation in Cleary’s books may feel trivial or whimsical when compared to adult literature, but they are no less powerful.

As Cleary’s books continue to age, it may become increasingly strange that Ramona wears her rainboots over her shoes or one character works at a company that sells horsemeat. It will stand out more and more that the characters are almost entirely white. But although the details of plot and setting will seem ever more antiquated, her characterizations remain familiar. If you yourself weren’t Ramona, you knew someone who was. “I have stayed true to my own memories of childhood,” she told The Atlantic in 2011. “Although their circumstances have changed, I don’t think children’s inner feelings have changed.” As those circumstances change, so do the ways in which children read, but Cleary’s publishers are making sure she won’t be lost in transition. To mark Cleary’s 100th birthday, HarperCollins has re-released three of her novels as The World of Beverly Cleary Collection in the most twenty-first century format: an ebook.