Memoirs and diaries about France during the

Second World War tend to share two characteristics. They hew to one of a few

narratives, either describing life under the Nazi occupation, such as Jean

Guéhenno’s classic, Diary of the Dark

Years, or describing life fighting the occupation, as in Agnès Humbert’s Résistance, Lucie Aubrac’s Outwitting the Gestapo, Marguerite

Duras’s The War, or Daniel Cordier’s Alias Caracalla. The second thing they share

is literary quality: Résistants, it

seems, make for superb writers. There is nothing surprising about this, given

the intellectual types who chronicled their experiences after 1945: Guéhenno

was a prominent literary critic and scholar; Duras was a novelist, Humbert was

an ethnographer and historian of art, and Aubrac was a teacher. Even Charles de

Gaulle’s Mémoires de guerre,

self-promoting and romanticized, has an aesthetic refinement that was

celebrated on its publication in 1954.

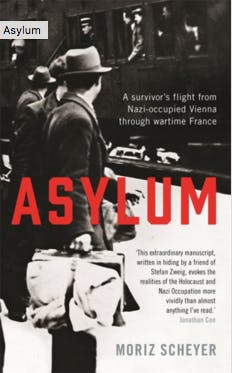

Moritz Scheyer’s recently translated memoir, Asylum: A Survivor’s Flight from Nazi-Occupied Vienna Through Wartime France, is like its predecessors a beautifully rendered story of survival against the odds—and one that encompasses the usual set of themes and emotions. Anger, especially, lies at the heart of Scheyer’s account, an outrage that spills out when he describes Germans as “ape-like creatures” and “Teutonic monsters,” or French collaborators as “worm-like” prostitutes. What distinguishes his book from others, though, is the setting in which it was conceived and written.

The Convent of Labarde sits on a hill near the

medieval town of Belvès in the Dordogne. Half hidden behind lime trees and

long since deconsecrated, the building is now a remote hospice for those suffering

from mental illness. There is no evidence of its more remarkable past: Between

1942 and 1945, while still a hermitage for Franciscan nuns, it was the hiding place of

Scheyer, his wife Grete, and their loyal housekeeper-companion Sláva. Under

the protection of holy sisters, it was here that Moritz composed his dramatic

and memorable account of life as a Jewish refugee in occupied France.

Before the war, Scheyer had been a critic at the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, one of Vienna’s foremost newspapers, where he published feuilletons on books and theatre. He was a friend of Stefan Zweig, as well as other cultural icons like Gustav Mahler, Bruno Walter, and Arthur Schnitzler. It was the last days of a city governed, he says, by “tradition and culture, of clear social orders and customs, of elegant love affairs”—the “epicurean” metropolis described so vividly by Zweig in his The World of Yesterday.

Everything changed in March 1938 with the Anschluss and Austria’s incorporation into Nazi Germany. What followed was deepening anti-Semitism, as well as what Scheyer calls the “ugly ‘Teutonification’ of [Vienna], which felt like a punch in the face.” Along with Grete, Sláva, and hundreds of other Jewish and left wing intellectuals, Scheyer left for France and into a life of indefinite exile.

In Paris, he was struck by the “politics of the ostrich”: the shared refusal to acknowledge the European crisis, the rise of fascism, and impending war with Germany. France was gripped by a “terrifying materialism,” while reactions to the Anschluss, as well as the occupation of Czechoslovakia, ranged from willful disbelief to indifference—“let’s have no unpleasantness,” he remarks acerbically. If anything captured this moral and political recklessness, the cynical self-centeredness, the Panglossian reverie, it was, he notes with scorn, the “despicable phrase ‘Drôle de Guerre’” (phoney war).

France fell in June 1940. Scheyer and Grete escaped in the mass exodus from Paris, “a raging torrent of suffering” that fled the advancing Wehrmacht. He describes the collective desperation and exhaustion of this great human caravan as it made its way toward the south of France (although his version is still less vivid than the one as told by Arthur Koestler in his memoir, Scum of the Earth).

By September, having been marked for arrest in Thétieu, Moritz and Grete were back in Paris (if they were going to get caught, it might as well be in their own home). Like other accounts of occupied France, especially Joseph Kessel’s L’armée des ombres, a semi-fictionalized account of Kessel’s time in the French Resistance, a recurring motif throughout the book is suffocation, and the imminence of arrest as the Nazi dragnet drew tighter around them. It was a life lived under the Sword of Damocles, as their world gradually disintegrated while friends, family, and acquaintances were arrested and disappeared.

Then in May 1941 Scheyer was detained and sent to a concentration camp in Beaune-la-Roland. Conditions were appalling, and life was geared around hunger and humiliation (German soldiers would regularly, and merrily, urinate on the prisoners). Lying in bed at night, the dorm a “symphony of misery and sorrow,” Scheyer was forced to confront his inner loneliness. But he also appreciated the fraternity that unites people in extremis, the worthlessness of barriers “erected between and against men by money, conceit, envy or prejudice,” and the sincerity of relationships that existed beyond barter and exchange—true comradeship.

In July he was released—a rare act of clemency on the part of his captors—and soon made his way with Grete across the Demarcation Line into the ‘Free Zone,’ which “bristled with all varieties of collaborative fauna,” glad to make common cause with the occupiers. Within a month, Vichy decreed all foreign Jews who arrived in France after 1936 to be sent to concentration camps. “Breathing space was over—yet again.”

Moritz and Grete were sent to a camp in Grenoble, a “Second Realm” between life and death, beyond which “the Third Realm— das Dritte Reich—… was a realm of agony.” But then another miracle: A doctor gave permission for them to leave the camp temporarily when Scheyer fell ill with a recurring heart problem.

After a failed attempt to escape to Switzerland, a nerve-shredding ordeal that almost resulted in their recapture, a family of Resistance organizers in Belvès, the Rispals, whom Moritz and Grete had met in early 1942, arranged for them to hide in the Convent of Labarde. “These were people who scarcely knew us,” Scheyer writes, but they had “voluntarily placed themselves in danger in order to help us. Such things still happened.” These are the real heroes of Scheyer’s book: Jacques, Gabriel, and especially Hélène Rispal, as well as Mère Saint-Antoine and the nuns of Labarde (yet more evidence that women made up the backbone of the Resistance).

Hidden but not safe, Scheyer records their life in Labarde, which, until the Liberation in 1945, felt like an agonizing stay of execution. An especially poignant moment comes in the autumn of 1943, when they are given a radio and rediscover the symphonies of Beethoven, Mozart, and Mahler, which transports them back to Vienna before 1938, before the strains of the Philharmonic were replaced with stomps of Nazi jackboots.

What makes this chronicle different from others is also the range of experiences it covers: from the Anschluss in 1938 to the Liberation of Paris in August 1944, via the phoney war, the exodus from Paris, imprisonment in two concentration camps, a botched escape to Switzerland, dealings with the Resistance, and life hidden in a convent—all rendered in the singular prose of an accomplished literary critique. As P.N. Singer, Scheyer’s grandson who unearthed the text in 2005, points out in his marvelous introduction, chapters on Eugène le Roy, or Charles Ordeig—head of a Resistance network formed from immigrants—bear the hallmarks of the feuilleton: attention to detail, concise summary of argument, and the emotional, rather than purely analytical, response to subject matter.

But it is the unique setting of Labarde that captivates, the sharp contrast between an island of acceptance, shelter, breathing space, and semi-safety, against the “turbulent hostile sea” in which the Scheyers were hunted, and into which they would soon return. Labarde had its imperfections and was, he says, “human, all-too-human,” but it heard the cries of oppression when most did not.