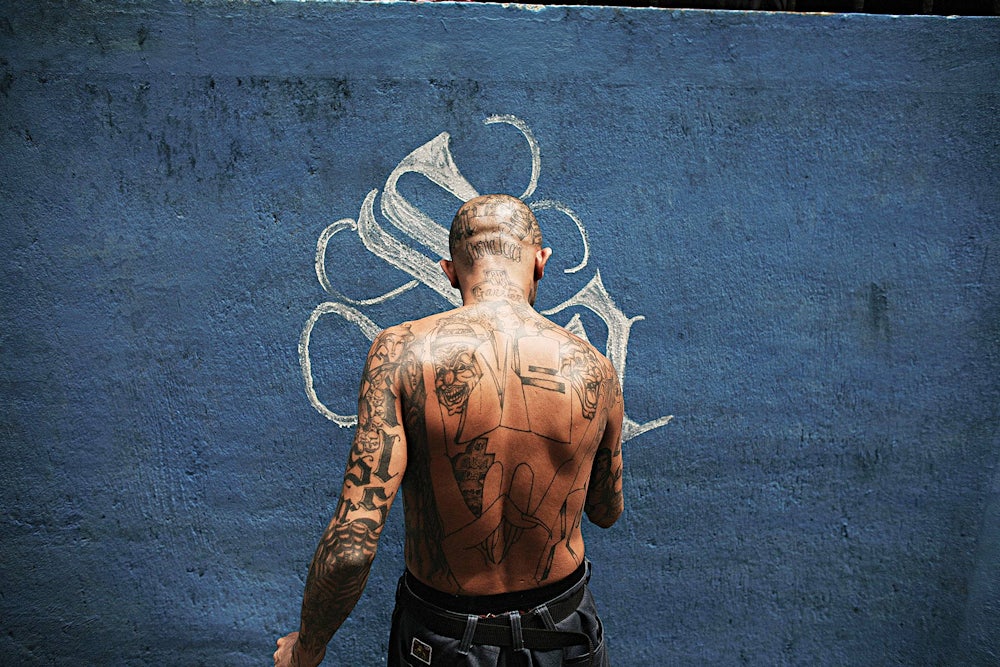

El Niño Hollywood was a scrappy preteen, dirt-poor and wide-eyed, when he met Chepe Furia. The 26-year-old, hardened by the Mara Salvatrucha gang on the streets of Los Angeles, had recently returned to El Salvador to build his child army. It was 1994. Furia flashed his shiny truck and brand-name clothes to reel in El Niño and two dozen of his adolescent friends. In abandoned houses in the province of Ahuachapán, he told stories of great battles against the Barrio 18 gang, and forced the boys to beat the hell out of each other. He showed them his weapons: one 9mm and two .22-caliber pistols. That was it—they were in.

Furia named his new posse the “Hollywood Locos” and declared war on the rival gang. El Niño was 15 years old when he grabbed one of the pistols and, to impress Furia, shot a Barrio 18 member, slitting his throat for good measure. He and his fellow apprentice assassins would drink and smoke pot at Furia’s two-story house, which served as a lookout for police. Some of the boys would arrive still wearing their school uniforms.

Nearly two decades later, in 2012, when Óscar Martínez started reporting about El Niño for El Faro, a San Salvador–based online publication dedicated to investigative journalism, the gangster was living in a shack with his teenage wife, smoking crack to pass the time, cocking the triggers of two pistols at the sound of any stir. Whole swaths of El Salvador belonged to the gangs, making the country one of the most murderous in the world. El Niño himself had 56 kills: “About six women and the rest men. I’m including faggots as men, ’cause I’ve killed two faggots,” he bragged to Martínez.

But fortune had caught up to El Niño. He was 29—over the hill in gangster years. His murders and several stints as a protected witness had flooded the valley with his enemies, and he knew his time was running out. Martínez, aware his reportorial project had an expiration date, started visiting El Niño once a month. El Niño welcomed the visits—he had nothing to lose—and awaited his own death.

The story of El Niño Hollywood snakes through Martínez’s new book, A History of Violence: Living and Dying in Central America, a compilation of 14 articles Martínez wrote between 2011 and 2015 for the crime investigations desk of El Faro, translated by It’s the story of how a war-torn region became a gang-torn one and how the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras have categorically failed to protect their young men and women from becoming victims of the gangs, and in many cases, from becoming the victimizers.

Martínez dives into the underworld of his subjects, navigating barrios that police won’t enter, spending days and nights with gang members. His methods resemble war reporting and his prose is cinematic. He describes a scene in which he and his brother—an anthropologist, equally lionhearted—are waiting in a truck on the side of a rural road.

Then, suddenly, El Niño burst onto the street. He had a short machete in his hand and his hand cannon and five 12-gauge cartridges on his belt. He was wearing the same balaclava that he wore on top of his head like a hat during the first trial. He jumped in the backseat of the pickup (my brother Juan was in the passenger seat) and started frantically looking around, obviously frightened. “Hit it! Hit it!” he said. “Step on it!”

This adrenaline rush will be familiar to those who read Martínez’s first book, The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail, in which he followed migrants, coyotes, and drug lords on the journey north undertaken by tens of thousands of Central Americans each year.

That book won Martínez critical acclaim in the United States and Europe, and in Latin America it reinforced his reputation as one of a few journalists willing to dig at the grime under the fingernails of the Mexican government. His new book—which pries its histories of violence from the lips of corrupt officials and the paranoid minds of gang members—is no less fearless.

In January, I moved to San Salvador to work as a freelance journalist and to write a book about trauma among survivors of a 1981 massacre. Soon after I arrived, I ran into Martínez at a party. We talked about a 23-year-old Salvadoran radio journalist who was shot to death on March 10 for refusing to give information to local gang members—they sliced his tongue off with a machete.

When I asked about the risks he faces, Martínez told me that reporters like this young man—who lived in a barrio saturated with gangs—have it much harder than he and his colleagues do. Martínez knows how to tourniquet a bullet wound, but he probably won’t ever need to do so because he avoids situations where he could be a target. At the end of the day, he sleeps in a house with private security. “If I get shot and bleed to death, it’s my own fault,” he said.

I understood. I first started reporting in El Salvador as an undergraduate. Over the years, as my ignorance about the gangs pushed me to read and ask questions, as the monster under the bed has become a network of sources, and as my skittishness has slowly dissipated, I’ve come to realize that whatever fear I experience can’t compare to the relentless terror of living in a gang-controlled neighborhood, unable to leave.

Martínez has reported in much more dangerous places than I have. So far his instincts have served him well, and El Faro has sent him out of the country when he has received threats. Still, the unspoken rules of reporting in El Salvador—drive with the windows up, call the gang leader before arriving so he’s not taken by surprise—are a constant negotiation of fear and trust with one’s sources and with oneself. Martínez has been called reckless for getting too close to gangsters. I worry less about his body and more about his spirit.

Martínez sees a widening gulf between the gangs and the rest of the population, and he’s trying to build a bridge before it’s too late. By publishing in English, he confronts an additional challenge: How do you make insulated Americans care about far-off El Salvador? How do you nudge the needle from apathy to action? At his least effective, Martínez’s explanation of why we should care, comes across as saccharine moralizing: “My proposal is that you know what is going on. … This book is about the lives of the people who serve you coffee every morning.” He’s right—but guilt doesn’t change policy, or sell books.

More effective are the parts in which Martínez marvels at the “logic of an ape” that led U.S. politicians to deport 4,000 gang members from Los Angeles back to El Salvador in the ’90s. The gangs spread like poison: Authorities now estimate there are 60,000 active members in El Salvador, with half a million more—relatives, business partners—dependent on the gangs. The problem has come full circle, Martínez insists, mentioning the exodus of Central American migrants to the U.S.-Mexico border. Whoever dreamed up the mass deportation of gangsters, he writes, “spat straight up into the sky.”

In the first two sections of the book,

“Emptiness” and “Madness,” Martínez aims to debunk the notion that the

Salvadoran government is united against the gangs. It’s not. By the early

2000s, Chepe Furia and his murderous youth group had finagled their way into

the political echelons of Atiquizaya, a town of 30,000 near the border with

Guatemala. The gangster was renting his white Isuzu dump truck to the mayor for

trash collection, snagging $2,500 a month, and using his connections—--a

spokesman for the mayor moonlighted as Furia’s treasurer—to operate a slew of

businesses, legal and illegal, from car dealerships to a drug distribution

network. To make matters worse, every time a dogged police inspector captured Furia

and sent him to jail, a circuit court judge went out of his way to get the

gangster released. Finally, in 2012, with the help of El Niño’s testimony,

police and prosecutors succeeded in locking up Furia for murder. The crooked

judge remained on the bench.

Mind-boggling corruption is the norm in Central America, and it offers one explanation as to why governments here have failed so miserably at defeating the gangs. Policemen and politicians are rendered powerless by the gangster hydra: Slay or imprison one top leader and another emerges to take his place, fattened and shielded by the corrupt officials who should be wielding the sword.

This impotence would be laughable if it weren’t so devastating. Salvadoran President Sánchez Cerén declared war on the gangs in January 2015, backing shoot-to-kill policing and a Supreme Court ruling that classifies gang members as terrorists. Violence in El Salvador soared: 6,657 people were murdered last year, among them 63 police officers and 90 children. El Salvador’s homicide rate, 103 murders per 100,000 residents, is more than 25 times that of the United States and a hundred times that of England.

A History of Violence also documents Martínez’s search for a narrative form to suit his message. The collection’s strength lies in his ability to write the hell out of his material, a skill he picked up by reading old stacks of The New Yorker and observing how writers like Alma Guillermoprieto and Jon Lee Anderson, who wrote the introduction to the book, used the tools of novelists to make true stories come alive. This kind of journalism is sorely needed in Central America, where the mainstream press refers to gang members as “delinquents” and “terrorists.” A History of Violence lets them speak for themselves. Like Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers and Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family, it skimps on statistics and analysis, instead relying on description alone to create a world that captures the reader and doesn’t let her go.

One of the stories, “El Niño Hollywood’s Death Foretold,” evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Like the beloved Colombian writer, Martínez pens scenes that are suspenseful, moving, and vivid. Sometimes they lack context, jumping around in time and place, weaving in and out of the minds of different characters—an unfamiliar reader may feel parachuted into gangland. Without Martínez’s skilled storytelling we might never read about these gangs in the first place. But by showing us violence up close, Martínez skirts the danger that his brutal narratives will be read as fiction.

I read the last section, “Fleeing,” while on a plane from San Salvador to New York. I’d spent the night with coroners, driving from murder scene to murder scene, lifting bodies into big black trash bags, and shoving the bags into the back of a pickup. One young woman had been shot in the chest so many times I thought the bullet holes were a pattern on her shirt.

As the plane lifted off the ground, I put down the book. It occurred to me that most Americans will never understand what it means to flee. Unlike the men and women for whom violence is everyday life in Central America, we can simply leave.