Gun control, according to the bumper stickers and GOP presidential candidates, is using both hands. Tell that to the nine-year-old girl who killed Charles Vacca in August 2014. Vacca, a gun range instructor in Arizona, was helping the girl fire an Uzi at the Arizona Last Stop Gun Range; after a few rounds, he let the girl hold the gun herself. But even with two hands, the recoil on the fully automatic weapon was too much for her, and the first shots jerked her hands upward, raising the barrel towards Vacca, who was shot once in the head.

How to control a thing that spits fire and jerks with such tremendous ferocity? It was not the time then, nor is it now, to ask how such an accident could have been prevented—whether a nine-year-old should have been given access to an Uzi, for example. This accident was unforeseeable, completely random, seemingly destined to occur. It was a time to mourn, a time to reflect on the preciousness of a life, gone in an instant. But it was also, apparently, not a time to change our behaviors, our regulations, or our laws. The children of Charles Vacca, in a letter they subsequently released to the unidentified girl, were clear that they harbored no ill will. “You’re only 9-years-old,” they wrote. “We think about you. We are worried about you. We pray for you, and we wish you peace.” Everyone’s sad, everyone’s broken up about this. Accidents happen.

As the political debate over gun control stagnates and stalemates, sadness is all we have left. White men will continue to display AR-15s openly and brazenly, threatening mosques and people they don’t like in the name of the Second Amendment, like the slave patrols of the Antebellum South. Mass shooters will continue to walk around with guns drawn, law enforcement powerless to stop them until they start firing. Black men and women and young children will continue to be shot on sight for holding pellet guns, or for any vague movement that might be later classified as “reaching for a waistband.”

There is still a fight to be fought, still letters to be

written and petitions to be signed, still legislators to support, still

elections to turn out for, but it’s clear that in the coming years nothing will

change, and toddlers

will still kill more Americans than terrorists do. Out of respect for the

victims, we must be sure to do nothing. It’s okay to be sad, but it’s

disrespectful to politicize the tragedy. Let us mourn and move on. These things

happen everyday.

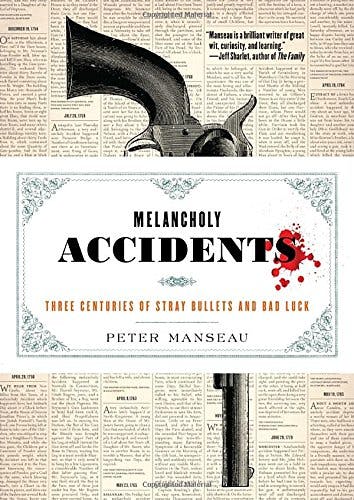

Peter Manseau’s latest book Melancholy Accidents: Three Centuries of Stray Bullets and Bad Luck, enters into this conversation to remind us not only how little has changed, but also how long we’ve been sad about guns. The book is a collection of news reports, from 1739 to 1916, all of which detail firearm accidents, most of which are fatal. The title comes from the most common description of these events, as in this piece from The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, dated September 12, 1790:

A melancholy accident happened a few days ago. A gentleman, being seized in the night with a delirium, imagined he was beset by robbers and assassins, and making a great noise, a servant and his own son got out of bed and entered the room, upon which he discharged a fowling piece at them, and wounded his son, who lies without hope of recovery.

Or the story that ran in the Suffolk Gazette on November 17, 1810:

Melancholy accident. We are informed that Mr. Elias White, of Westhampton was accidentally shot on Thursday last by Mr. Jonathan Reeve, as they were hunting in the woods. They were in pursuit of a deer, and the unfortunate man was mistaken in the thicket for the animal. He has left a numerous and destitute family.

It is a depressing litany, to be sure, though often unexpectedly poignant. “At Demopolis, Ala.,” runs a story from 1849:

A few days ago, several little boys, under 9 years of age, got possession of a gun which was supposed not to be loaded, and, providing themselves with a box of caps, amused themselves with snapping the gun. After exploding nearly forty caps, one of the boys pointed the gun at another, told him he believed he would shoot him, and pulled the trigger, when the gun unexpectedly went off and killed the little fellow on the spot.

And, depending on your predisposition, it is also occasionally humorous: “Henry Haynes, of Peoria, who accidentally shot his mother-in-law, has made three attempts to commit suicide,” The Times Picayune reported on October 8, 1874. “Some folks may sneer at him, but when one sits down and calmly reasons the thing, he must admit that it is hard to lose a mother-in-law just as the preserve season is at its height.”

With no article over two pages, and all bearing a distinct simplicity of prose, economy of facts, and terseness of affect, Melancholy Accidents traces its lineage to Wisconsin Death Trip, Michael Lesy’s 1973 groundbreaking collection of singularly bleak photographs and news reports from Black River Falls, Wisconsin in the late nineteenth century; Novels in Three Lines, the posthumous collection of Felix Feneon’s unsigned fait divers columns from the early twentieth century, each reducing a news story to a three-line report; or Teju Cole’s recent Small Fates Twitter project, wherein he similarly translated the news of the day from Lagos, Nigeria into 140-character tweets. Again and again the unsung and often unnamed prose stylists of wire reports and local newspapers churn out stories that are repetitive in their sameness, while nonetheless evoking the contours of a family, a history, a unique life whose loss can only be approximated here. Taken as a whole, they are what Manseau, in his introduction, calls a “forgotten mode of American storytelling”: the economical story of an accidental death, a brief memento mori to be read alongside the news of the day.

Throughout these reports, what’s repeatedly stressed is the loss of a productive citizen: victims are described as “a valuable young man,” “a promising boy,” “a very promising son,” “a fine girl in the bloom of youth.” Writers always stress, further, that there is no malice here: When brother shoots brother, accounts stress their close bond, to dispel any hint or suggestion of foul play. “The grief of the brother who had fired the fatal shot knew no bounds,” reads a report from Chicago of an eleven-year-old killed by his 13-year-old sibling. “He wept and moaned and declared that he wanted to kill himself too. When the police arrived he begged to be taken to the station, and told Lieutenant Noelle that he should lock him up in the cell. The boy was permitted to go home, as the shooting was accidental.” But even more important is the recognition that the gun is always blameless, as is (almost always) the wielder. Accidents happen.

The stories in Manseau’s book are anti-morality tales: There is no mention here of the guilt, either by hubris or folly, of the shooters; there is no hint that the victims were in any way deserving of their fates. Nor is there mention of God anywhere in these items: He does not appear to punish the wicked or the guilty, nor are these accidents proof of His omnipotent (if mysterious) wisdom and divine plan. These are not occasions to ponder how a benevolent God allows evil and tragedy to exist in the world.

Instead there is only randomness, and our submission to it. Manseau has previously explored the theological underpinnings of America, in books like his most recent One Nation, Under Gods: A New American History. But here he has found an America completely devoid of the divine, where the only force that reigns is a cruel and apathetic fate.

The term of art in Manseau’s book is the “melancholy” of its title: These reports, taken together, are not just a history of firearm accidents but also an archive of melancholy itself. For in the absence of a morality play with guilty parties, or an affirmation of a divine plan that may someday be known to us, what is left? Melancholy, here, is perhaps the best and most appropriate response to the overwhelming indifference of nature, a world that arbitrarily takes young boys and girls, along with mothers and mothers-in-law, all without pity.

Which is not to say that pessimism and futility are the only responses to our firearm epidemic. After all, Australia responded to the horrific mass shooting at Port Arthur in 1996 by banning sales of nearly all firearms, government buybacks of outstanding weapons, and tightened restrictions on gun ownership, leading to a significant decrease in death by firearms. That’s the kind of progressive, Whiggish understanding of history that we usually associate with the great, forward-leaning United States of America: a problem is identified, its causes are analyzed, and a remedy is enacted.

But our approach to gun violence is both more cynical and impotent. Our long-standing obsession with guns and the harm they do reveals how fatalistic our nation is, how empty its rhetoric about progress is. This is the deal that guns rights advocates have made with the Devil: in exchange for unfettered access, they have abandoned a moral universe in favor of nihilism. What Manseau’s Melancholy Accidents reveals above all is that while we may call ourselves a nation under God, the god we worship first and foremost is Fate.