On a recent overcast morning, eight floors above the Hudson River in a large-windowed reception room at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, an audience gathered for the preview of a new exhibition listened patiently as various members of the institutional brass ticked off a predictable list of acknowledgments—curatorial colleagues, installers, support staff, financial backers. When it came time for curator Jay Sanders to speak, he added to his remarks a shout-out to a less familiar figure, the museum’s general counsel, and the “great legal team he brought in to help us navigate this new territory.” The territory to which Sanders was referring was Astro Noise, a new exhibition by Laura Poitras. The show was a risk, as pretty much everyone associated with it acknowledged, not just for Poitras—who while well-known as a filmmaker and journalist had scant experience showing artworks in a gallery setting, let alone a museum—but also for the Whitney itself, which was about to debut an exhibition built around classified surveillance images and security documents.

Poitras is the director of last year’s Academy Award–winning documentary Citizenfour, which followed Edward Snowden, the courageous—or traitorous, depending on your politics—former National Security Agency subcontractor who, in 2013, fled to Hong Kong with a trove of classified documents detailing a startling range of clandestine American surveillance programs. Poitras herself has been the recipient of the unwanted attentions of government officials; by her count, she has been detained and interrogated at the U.S. border more than 40 times since 2006 when, after working in Baghdad on My Country, My Country, her film about Iraqis living under the American occupation, she was placed on a terrorist watch list. These two films, along with The Oath—a 2010 documentary about the divergent fates of Abu Jandal and Salim Hamdan, two members of Al Qaeda who were intimates of Osama bin Laden—form what Poitras has called her 9/11 trilogy. Together they have made her one of the most visible artist-activists in the world.

In early 2013, Poitras had just begun receiving the mysterious emails that would alter the direction of her life. She had by then a significant track record as a documentarian—she’d won a MacArthur “genius grant” the prior year—but when she started to consider a way to present her correspondence with this stranger, her first thought was not to make a film, but a work of visual art. She reached out to Sanders—the curator who had included her in the 2012 Whitney Biennial—for advice on an installation project, a form she felt was better suited to the material. Of course, Poitras changed her mind, and Citizenfour was a tour de force of precisely the type of work she had initially thought ill-suited to tell the story she wanted to tell. But the fact that it very nearly became an exhibition suggests that Astro Noise shouldn’t be thought of as an outlier within her practice, but rather as an instance of a particular mode of presentation that had only been waiting for an opportunity to express itself.

Poitras enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute in the late 1980s, where she studied with leading avant-garde filmmakers Ernie Gehr and George Kuchar and encountered the work of other pioneering experimentalists like Stan Brakhage, Peggy Ahwesh, and Abigail Child. Poitras decided not to pursue a further education in art, instead moving to New York to study political theory, and Astro Noise, with its mix of journalistic bluntness and highly conceptualized presentational display, might best be understood as the convergence of these two formative experiences. It shows clear evidence of both her early immersion in a particular strain of discourse about what film could potentially be—outside of the frontal, narrative, single-screen-based conventions that shape the usual sense of the form—and her deeply felt relationship to questions of social justice, one that has played itself out in the sophisticated brand of advocacy journalism she’s pursued over the past decade.

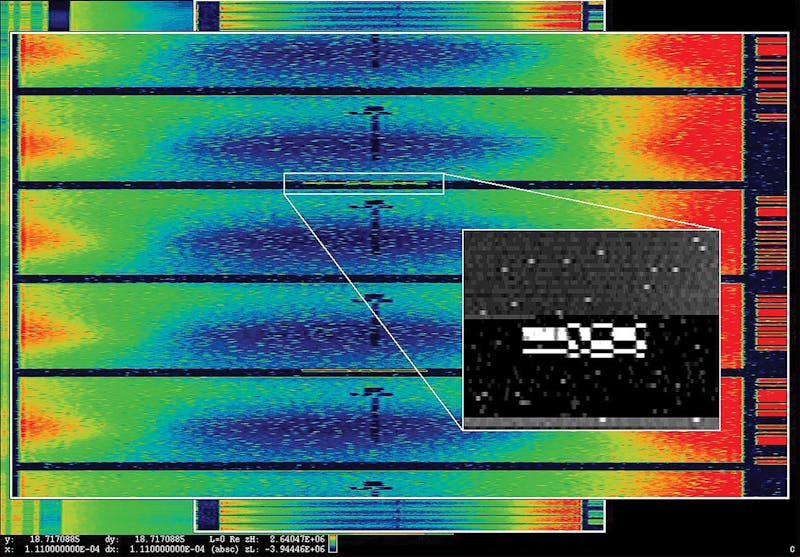

The hybridity central to the character of Astro Noise—its commingling of fact and fiction, data and drama—is evident before one even enters the exhibition proper. In the hallway outside the first darkened gallery, visitors encounter an array of six large and colorful images. Though they have the look of late-period Gerhard Richter paintings, their vibrant abstractions are rich with information, and the story of how they came to be carries with it a fitting whiff of journalistic intrigue. Just days before the opening of the new show, Henrik Moltke—a Danish filmmaker and journalist who has over the years worked with Poitras on reporting stories such as the clandestine relationship between the NSA and AT&T and who was part of the Astro Noise exhibition team—had published an article with his colleague Cora Currier in The Intercept, the online magazine Poitras founded with Glenn Greenwald and Jeremy Scahill in 2014, about a joint American-British program code-named “Anarchist” that tracked and gathered data on the activities of Israeli drones and military aircraft. Picked up by news organizations around the world, the story, which was based on information provided by Snowden, included a series of images—blurry photos of aircraft and what appear to be target sites—and referred to others that, the article noted, “would be on view as part of Intercept co-founder Laura Poitras’ solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.” Like the story itself, these classified images had apparently been held back until just before the opening. Now presented as sumptuous ink-jet prints mounted on large aluminum panels, six of the kaleidoscopic Anarchist images—transformed from evidence into artwork—were positioned as teasers for Poitras’s show.

Like the transmutation of the Anarchist images for the purposes of publicizing the exhibition, the other transformations willed, sometimes uneasily, by Astro Noise—of journalist and filmmaker into installation artist, of dryly bureaucratic source material into de facto artworks, of visitors from passive consumers of information into participants in an activated experiential space—reveal a documentarian-cum-artist with a conceptual foot on either side of the fence. In excerpts from her diary, which she has reproduced in Astro Noise: A Survival Guide for Living Under Total Surveillance, the substantial book created to accompany the show, Poitras explicitly acknowledges her frustrations with the documentary approach, calling My Country, My Country “naïve,” and ruefully commenting, “As if appealing to people’s consciences could change anything.” And yet this sense of disillusionment hasn’t totally dissuaded her from continuing to rely on certain conventionally cinematic approaches—Astro Noise has a clear narrative arc, moving from a scene-setting beginning to an explanatory middle to a surprise ending—or from deploying archival artifacts and techniques for their ability to evoke the power of the “real.” Perhaps its greatest divergence is in its temperament, its seeming skepticism toward attempts to conjure the sort of “conscience change” usually courted by documentary practice. In contrast to the clarity, directness, and finely detailed observations that are the hallmarks of her films, Astro Noise trades in fragmentation, abstraction, and disorientation.

The show is divided into several discrete sections and starts. After the introductory encounter with the Anarchist images is O’Say Can You See, a pair of videos projected on two sides of a large screen suspended in the middle of the initial room, effectively cutting it in half. Arriving viewers first see a series of slow-motion images of people staring out toward them—the footage is actually of crowds that gathered in lower Manhattan in the days following the attacks on the World Trade Center to stare at the space where the towers once stood. The video is accompanied by a low-volume recording—altered and deformed by Poitras in the manner of another September 11–related audio project, William Basinski’s brilliant Disintegration Loops—of the performance of the national anthem at Game Four of the 2001 World Series, which took place roughly seven weeks after the attacks and three weeks after the U.S. began bombing the Taliban in Afghanistan. Playing on the other side of the screen is a grainy military video of an interrogation of two Afghan prisoners, Said Boujaadia and Salim Hamdan, both of whom were eventually sent to Guantánamo. (Hamdan is the same man Poitras focused on in The Oath.)

Poitras has shown the Ground Zero footage a handful of times before as a single-channel video. Essentially a documentary project given an aesthetic fillip, it does have an uncanny allure, and if its newly conceived juxtaposition here with the interrogation footage has something of the shape of a one-liner, overall the piece’s spatial logic, which prevents the viewer from being able to see the two videos at once, does effectively physicalize the political incapacity to see more than one side of a situation. Meanwhile, Poitras’s larger point—that both the somber rubberneckers and the military officials, whose dialogue with the prisoners is constantly shadowed by confusion and misunderstanding, are engaged in the same activity, namely looking for answers to questions that they can’t quite articulate—makes an apt entry point into the rest of the show.

If O’Say Can You See functions like a précis for Astro Noise, the next two environments along the show’s determined pathway form its narrative core. Bed Down Location features a carpeted platform on which visitors can lie back and gaze up at a ceiling showing projections of the night sky taken from locations in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia—all places where the U.S. government uses unmanned drone aircraft to conduct so-called targeted killings of persons it deems to be threats. (A “bed down location” is military jargon for the place where such individuals sleep.) It’s an affecting scenario—there’s a helplessness to being on your back amid strangers in a dark, public place, and a palpable empathy provoked by staring into the quiet, deadly expanse of stars—although Poitras’s decision to include in the sequence daytime footage shot over a Nevada Air Force base in which the drones, eerily invisible in the foreign skies, are now all too visible, might be counted as an instance in which her documentarian instincts to make something incontestably clear works against a more effective form of emotional disquiet.

The problem of seeing, both literally and metaphorically, is also the central conceit of Disposition Matrix, an L-shaped corridor featuring 20 slots that each contain some artifact related to the U.S. government’s post–September 11 policies. (Again, the title of the work borrows from military terminology—it’s a phrase coined to describe the streamlined database established by American counterterrorism officials for tracking, capturing, or killing enemies of the state.) Placed at various heights, including some awkwardly low positions on the wall, the cutouts are about the size of a mail slot and can only be viewed fully by one person at a time. The space was designed to produce a certain kind of spectatorial anxiety. It puts visitors waiting for their turn in the position of being lurkers, trying to catch a glimpse of the contents of a slot over the shoulder of the person in “control” of the view, yet it also makes viewers less likely to spend time with the objects. This is not a problem for most of the items on display—classified memorandums, documents diagramming various forms of surveillance, and the like can be taken in relatively quickly—but in the instance of the more involved artifacts, such as a filmed interview conducted with Murat Kurnaz, an innocent Turkish man extrajudicially detained for more than six years in both Afghanistan and Guantánamo, Poitras has followed her artistic rather than journalistic impulses, making the conscious decision to sacrifice content for the sake of form.

This is not the case with November 20, 2004, the show’s penultimate work and both its least mediated and most autobiographical. Less a fully formed project than an explanatory appendix, the piece consists of an eight-minute video the artist shot on the roof of a Baghdad home during fighting in the aftermath of a raid on a nearby mosque the previous day. Accompanied by a short explanatory voice-over, November 20, 2004 was the video that began Poitras’s journey down her own rabbit hole of surveillance and harassment—a journey explicated in 2015 when she successfully sued the government to obtain the files that were kept on her, some of which are shown in the redacted form in which she received them as large transparencies on the wall adjacent to the video screen. The message here is clear—Poitras is herself part of the larger story she is telling—and the show’s final twist invites us to similarly acknowledge our own involvement in the process, as a video display near the exit reveals that, unbeknownst to those still in the dark spaces of the galleries, software has been tracking visitors’ physical locations, shown in an infrared image of the recumbent bodies beneath the video skies of Bed Down Location, as well as their digital traces, seen via a rolling list of Wi-Fi signals produced by their cell phones and personal devices.

This final moment is meant to be a striking coup de théâtre, yet one wonders if the gesture comes as the surprise it was intended to be, given the riddled world Poitras has revealed through her work, one so utterly shot through with opaque all-seeing surveillance. Astro Noise is in some sense designed to redeem the status of the individual as a free and willful subject in the face of such systems, from the relatively benign to the deeply malign, that cast each of us as a walking, talking set of data points to be tracked, measured, and analyzed for various social, political, and economic ends. Poitras’s decision to come at these issues from the perspective of art-making, as opposed to journalism or documentary filmmaking, is clearly an attempt to return to her audience a microcosmic sense of agency—to socialize and embody her issues, to allow viewers to engage with rather than simply be told about them. And one gets the strong sense that the effort is not simply for the benefit of her viewers, but that the show is also an attempt on Poitras’s own part to claim a greater measure of control over her practice—to become more auteur than reporter, to shape rather than be ever shaped by the material with which she deals.

In his book The Practice of Everyday Life, the French intellectual Michel de Certeau differentiates between “strategies,” which he says are the province of strong and organized institutions, and “tactics,” which are deployed by the weak to evade the structures that seek to control them. He wrote that the central goal of his study was “not to make clearer how the violence of order is transmuted into a disciplinary technology, but rather to bring to light the clandestine forms taken by the dispersed, tactical, and makeshift creativity of groups of individuals already caught in the nets of ‘discipline.’” One can hardly blame Poitras for seeking new forms of language with which to sound her alarms, and there’s nothing to suggest Astro Noise should be taken as a permanent change of course for the artist—a new documentary, focusing on WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, is scheduled to come out later this year. If the show feels less than fully persuasive—either as presenter of ominous fact or conjurer of sinister fiction—it does highlight the dilemmas facing those citizens who wish to expresses their resistance to the excesses of the security-state status quo. Poitras has devoted her reporting and filmmaking to revealing the strategically cast disciplinary nets in which we all find ourselves caught; her art-making is clearly designed as a nascent attempt to develop alternative tactics that might cause real disturbances in their pervasive systems of control. Yet history suggests that such technologies do not relinquish their hold easily, and the question that remains unanswered by Astro Noise is whether Poitras’s move from the world of journalism and mass media to the context of the contemporary art museum signifies an advance or a retreat in the face of their relentless pressures, whether it constitutes a confident assertion that her work has the power to make a real difference in the world, or a tacit acknowledgment that it finally does not.

This article has been updated.