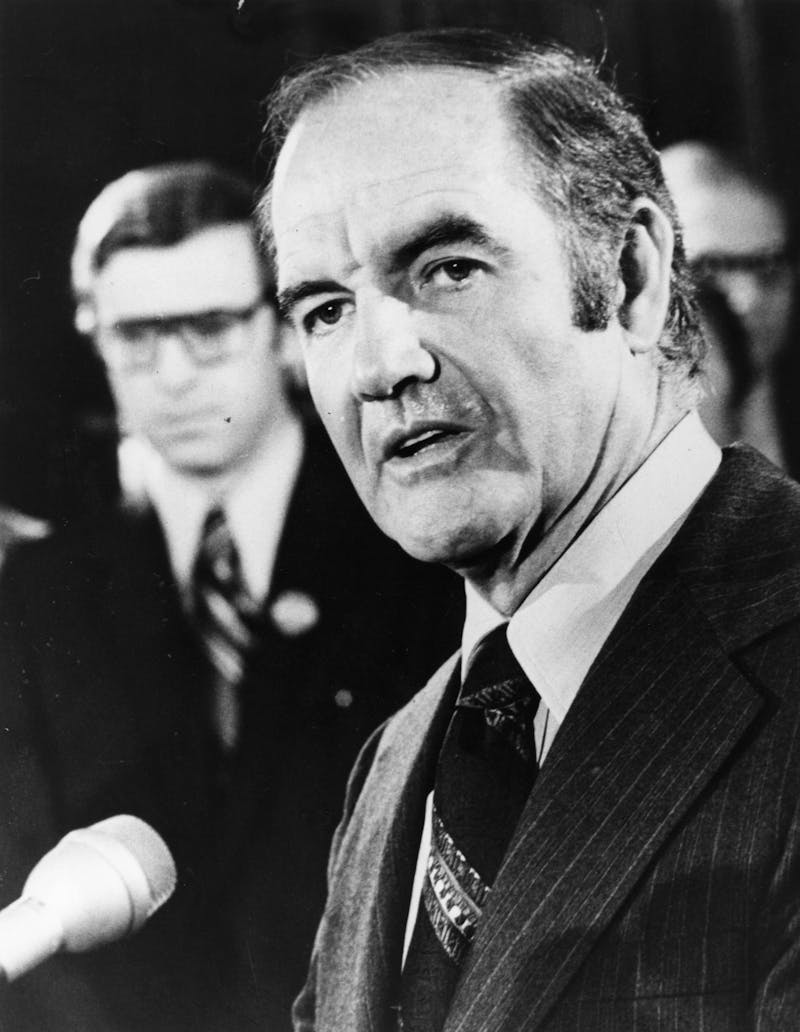

A specter is haunting the Democratic Party—“McGovernism.” In 1972, President Richard Nixon shellacked his Democratic opponent, George McGovern, by a 23-point margin in the popular vote. Following McGovern’s defeat, Democrats began running towards the center and haven’t looked back, even though that center seems to have moved further and further to the right with each passing election.

For the past 40 years, whenever a Democratic presidential hopeful has given off the slightest whiff of leftish anti-establishmentarianism, party leaders and mainstream pundits have invoked McGovern’s name. In 2004, Howard Dean was the new McGovern. In 2008, Barack Obama became the new McGovern. This year, it’s Bernie Sanders’s turn.

But the Democrats’ fear of McGovernism is misplaced. McGovern didn’t lose because he was too far to the left. He lost because he was facing a popular incumbent presiding over a booming economy. Moreover, the Democrats’ belief that they need to steer clear of McGovernism, assuming it was ever correct, now looks increasingly misguided. With each passing decade, the types of voters drawn to McGovern’s 1972 campaign have become a larger and larger share of the American electorate, while the issues championed by McGovern have become more and more salient.

Instead of looking at Bernie Sanders and seeing George McGovern, Democrats should reconsider McGovern himself: He should have become the party’s Barry Goldwater. Lyndon Johnson’s 22-point rout of Goldwater in 1964 was, in many ways, a mirror image of McGovern’s defeat at the hands of Nixon eight years later. Indeed, in heaping skepticism on Sanders’s candidacy, New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait and MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow compared the Vermont senator to both infamous losers.

But such simple comparisons miss a key difference between McGovern’s loss and Goldwater’s loss. The GOP’s response to Goldwater’s landslide defeat couldn’t have been more different from the Democrats’ reaction to McGovern’s. Whereas the Democrats shifted away from McGovernism towards tepid centrism, Republicans ultimately embraced Goldwater’s radical conservatism, paving the way for Ronald Reagan’s eight Goldwater-esque years in the White House. Most importantly, the parties’ divergent responses to sweeping defeat at the ballot box explain a great deal about the state of American politics today, especially the Democrats’ inability to effectively counter either the expanding extremism of the GOP or the increasing economic inequality and persistent racism that Republicans’ Goldwater-tinged radicalism has facilitated.

From the beginning of his career in the U.S. Senate, Barry Goldwater tapped into a rich vein of movement conservatism dissatisfied with the moderate Republicanism of Dwight Eisenhower, which Goldwater denounced as little more than a “dime store New Deal.” Supported by big donations from rabidly conservative businessmen like

Roger Milliken and Fred Koch, and smaller sums culled via pioneering use of direct mail from John Birch Society sympathizers and upper middle class professionals in fast-growing Sunbelt suburbs, Goldwater finally captured the GOP nomination in 1964, after having privately cooperated with a “Draft Goldwater” challenge to Nixon, Eisenhower’s vice president, for the nomination in 1960. When Goldwater bellowed “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” during his ’64 RNC acceptance speech, he was speaking for the conservative Republicans who had longed for years to take over the party.

With the help of William Baroody, the president of the American Enterprise Institute, and libertarian University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, Goldwater put together a platform that within a few decades would become the template for every GOP presidential campaign that followed. Goldwater promised a bellicose foreign policy that would confront Communism, opposition to civil rights legislation grounded in “states’ rights,” antagonism towards organized labor, rejection of the welfare safety net, and antipathy towards the “moral decay” allegedly wrought by liberalism. In a sharp break from Eisenhower’s “green eyeshades” balanced-budget Republicanism, Goldwater also promised budget-busting tax cuts aimed at upper-income individuals and businesses, which Friedman suggested might not only pay for themselves with higher growth, but might also, according to proto-“starve the beast” logic, “put steady and effective pressure on Congress to hold down spending.”

Goldwater’s colossal defeat did little to dampen conservative Republicans’ belief that, with their help, Goldwater’s ideas eventually would defeat the twin evils of liberalism and moderate Republicanism. The Goldwater campaign was “the Woodstock of American conservatism.” It invigorated young conservatives, including Karl Rove, Pat Buchanan, Michael Deaver, Jesse Helms, and Richard Viguerie.

No Goldwaterite mattered more than Ronald Reagan, though. By 1964, Reagan had abandoned his youthful support for Franklin Roosevelt and the Democrats and was campaigning for Goldwater full-time. Reagan delivered what came to be known among conservatives simply as “The Speech” to group after group of loyal Republicans and, crucially, a national television audience just before election day. In what remains a legendary broadcast among conservatives, Reagan attacked the Democrats on high taxes and timidity in Vietnam, lambasted the liberal “intellectual elite” and welfare cheats, and praised Goldwater as a man who, unlike the crypto-socialist Democrats, would not “trade our freedom for the soup kitchen of the welfare state.”

With Reagan as their leader and the assistance of foot solders like Viguerie, who would use the list of Goldwater donors to deploy the power of direct mail on behalf of conservative causes and candidates for decades to come, conservatives regrouped from the 1964 loss and set about remaking the Republican Party in Goldwater’s image. Buoyed by his Goldwater speech and the backing of deep-pocketed conservatives, Reagan won the California governorship in 1966 and made a last-minute attempt as the conservative wing’s favorite son to prevent Nixon from winning the Republican Party’s 1968 presidential nomination. But when Nixon left the White House in disgrace, he took Republican moderates with him, giving Reagan and the conservative insurgents the upper hand. After nearly knocking off incumbent President Gerald Ford, Nixon’s former vice president, in the 1976 GOP primary, Reagan and the conservative Republicans who backed him completed the restoration of Goldwater conservatism in 1980 when Reagan secured the Republican Party’s presidential nomination.

Reagan’s 1980 campaign was pure Goldwater. He promised sweeping tax cuts and a “return to spiritual and moral values.” He pledged to take on Communists abroad and welfare “cheaters” at home. Most controversially, Reagan echoed Goldwater’s racist dog whistle by pledging to restore “states’ rights.” By following small-government conservatism, Reagan told the nation, America would be restored to “a shining city on a hill.” Reagan’s supporters cast their candidate as the heir to Goldwater’s throne. “Barry Goldwater was the philosopher,” John Sears, Reagan’s campaign manager, explained. “Ronald Reagan is the articulator.” For good reason, conservatives saw Reagan’s victory over Jimmy Carter in the general election as the complete vindication of Goldwater conservatism. By winning, Reagan placed views once seen as fringe conservatism squarely at the center of the GOP and demonstrated that all it takes is one fortuitous election to fundamentally shift the American political landscape.

Today, every Republican candidate prays at the altar of Reagan, not only by making his name a mantra, but also by making top-heavy tax cuts, muscular militarism, and denunciations of welfare a must for any GOP presidential contender. In reality, they’re genuflecting at the shrine of Goldwater. Such has been the GOP’s shift to the right that even the elements of Goldwaterism that Reagan downplayed for political expediency, especially the privatization of Social Security and Medicare, have found their way into GOP orthodoxy. For good reason, many liberals and conservatives now see Goldwater as perhaps “the most consequential loser in American politics.”

The same could not be said of George McGovern.

On a frigid January day in 1971 in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, McGovern entered KELO-TV’s studios to declare his candidacy for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. To call McGovern a dark horse candidate for the 1972 nomination would be an understatement. In August, Vegas oddsmaker Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder gave McGovern scant 200-to-1 odds of securing the Democratic nomination. Heading into the election year, McGovern’s poll numbers sat in the single digits.

But McGovern and his advisers had a plan to secure the South Dakotan the nomination and remake the Democratic Party in the process. Building off the same insight put forward by Nixon’s political wunderkind, Kevin Phillips, the McGovern campaign recognized that the South’s shift to the Republican column that began with Goldwater was here to stay. The McGovern team devised a two-pronged strategy to counter the South’s defection. First, McGovern would align himself with recent social movements to a degree that no previous Democrat had contemplated. This meant courting members of movements dismissed by many Democrats as mere “identity politics,” including African Americans, students, women, and gays and lesbians. This strategy would not only solidify African Americans’ shift to the Democratic Party, but also would add to the Democratic coalition a bevy of educated white-collar voters for whom issues like the Vietnam War or women’s rights were paramount.

The second prong of McGovern’s strategy was to woo poor and working-class whites in the North away from conservative Democrat George Wallace with a populist pocketbook pitch that foregrounded issues of economic inequality and the political power of the wealthy. Following decades of decline, income inequality began rising after 1968. At the same time, inflation was squeezing Americans’ pocketbooks, and the U.S. tax system was becoming less progressive, thanks to rising rates for low- and middle-income Americans and both falling rates and expanding loopholes for the rich. Seven in ten Americans in the 1970s agreed that “the tax laws are written to help the rich, not the average man” and “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” McGovern’s message echoed the public’s anger. “It is the establishment center,” he said, “that has erected an unjust tax burden on the backs of American workers, while 40 percent of the corporations paid no federal income tax at all last year.” McGovern promised to close tax loopholes for the rich and use federal revenue to provide low- and middle-income Americans with relief from rapidly rising property taxes. Most radically, McGovern united welfare reform and tax reform by proposing a “Demogrant” of $1,000 per year for every adult, regardless of income, as an alternative to Nixon’s complicated means-tested welfare overhaul plan.

The combination of McGovern’s outsider status and policy platform ensured that McGovern received support from few interest group leaders and outright opposition from most of the “Wall Street kingmakers” who had previously backed both Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. In response, the McGovern campaign tapped direct mail wizard Morris Dees to enable mass fundraising from small donors. The result was more than 40,000 contributions by February 1972 averaging less than $30. The McGovern campaign complemented Dees’s direct-mail machine with a sophisticated door-to-door get-out-the-vote effort in key primary states.

To the surprise of nearly everyone outside of the McGovern campaign itself, the strategy worked. In confidential memos, the Nixon reelection campaign called the George Wallace and McGovern efforts “the only two smart campaigns.” McGovern, in particular, worried Nixon’s advisers because his “class appeal” was “pinning the adjective ‘rich’ to Republicans.” McGovern had been “badly underestimated” and was “potentially very dangerous to the President,” the Nixon analysis concluded.

But the McGovern campaign began falling apart almost immediately after McGovern secured the nomination. At the Democratic National Convention, McGovern didn’t give his acceptance speech until nearly three in the morning. Making matters worse, McGovern and his advisers selected Senator Thomas Eagleton, an anti-abortion Catholic, as his running mate in a sop to the party’s more socially conservative wing. Though Eagleton had assured McGovern that there were no skeletons in his closet, it soon leaked that Eagleton had undergone electroshock therapy, and, after initially pledging his support for Eagleton, McGovern removed him from the ticket, a turn of events that made McGovern look both incompetent and cruel.

Perhaps the deepest damage to McGovern’s campaign came not from its own ineptitude, but from the candidate’s fellow Democrats. Early in the primaries, an adviser for Hubert Humphrey, one of McGovern’s main opponents for the nomination, promised, “We are going to show that McGovern is a radical, just like Goldwater was in 1964.” Keeping that promise, Humphrey claimed during a televised debate prior to the California primary that McGovern’s Demogrant plan would hike taxes on a middle class family making $12,000 by more than $400. The number wasn’t remotely true. According to both private calculations by Nixon’s Office of Management and Budget and independent academic estimates, the bottom 70-to-80 percent of families would pay less under McGovern’s plan than under existing law or Nixon’s proposals. But Humphrey’s claim not only stuck, it practically wrote the script for an anti-Demogrant commercial that Nixon would run in the fall.

As McGovern barreled toward the nomination, leading Democrats’ attacks became more desperate. Anti-McGovern Democrats staged an “Anybody But McGovern” movement at the convention. When that failed, some pledged that they would not campaign for him and might even support Nixon. A Democrat even handed Republicans their best attack line: “The people don’t know McGovern is for amnesty, abortion, and legalization of pot,” an unnamed Democratic senator told the press. Hugh Scott, the GOP’s Senate minority leader, transformed the quote into “the three A’s: Acid, Amnesty, and Abortion” and a golden political slur was born. (Ironically, the unnamed Democratic senator who had originated the line was none other than Eagleton, though McGovern didn’t know it at the time.)

By the time November rolled around, McGovern’s loss to Nixon was a fait accompli.

Democratic leaders’ response to McGovern’s defeat was swift and unequivocal. From the ashes of McGovern’s loss rose a group of disaffected Democratic campaign staffers and elected officials, soon dubbed the “neoliberals,” who promised to put the Democratic Party back on the winning track, which invariably lay to the right. The neoliberals and their biggest stars, such as Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis and California Governor Jerry Brown, called for a full-scale repudiation of not only McGovernism, but also the “New Deal ethic” that had animated Democratic politics since FDR. On foreign policy, they claimed that Democrats needed to reestablish their toughness and willingness to use the military to confront enemies abroad. On social issues like busing and gay rights, the neolibs urged Democrats to strike a more conservative tone, even if it meant shunting aside the very groups that McGovern had worked so hard to court. On economic issues, McGovern’s greatest sin in the eyes of the neolibs was precisely what had most worried the Nixon White House—his populism. The neolibs argued that economic growth, not income inequality, needed to be Democrats’ primary concern. The entrepreneurial class, they claimed, needed to replace the working class as the Democrats’ idée fixe—a shift that not coincidentally would make the party a more welcome home for the donations of big business and rich individuals.

Some Democrats balked at the neoliberal program. Speaking for the Congressional Black Caucus, Detroit-area Congressman John Conyers called the nascent neoliberal philosophy an “utter fraud.” Mexican-American labor activist Henry Santiestevan noted the cruel irony of some Democrats’ suggesting that the party abandon the New Deal “when many of us haven’t even reached the New Deal.” And liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith quipped that “Democrats have bought a slightly modified version of the Hoover trickle-down doctrine.”

But paleo-liberals were fighting a losing battle. Through the lens of neoliberalism, each Democratic presidential loss only served to prove the neolibs’ thesis that the party needed to move even further to the right.

In 1976, Jimmy Carter, who had led the “Anybody But McGovern” forces at the 1972 convention, mounted a centrist campaign that saw him take the White House despite running well behind Democratic congressional candidates across the country. Once in office, Carter shifted to the right. Despite campaigning on McGovernesque promises to close tax loopholes for the rich, Carter signed into law a huge capital gains cut that gave 90 percent of its benefits to the top 10 percent of taxpayers. To this, Carter added a bevy of additional initiatives—including deregulation, fiscal austerity, and monetary restraint—that amounted to “slouching toward the supply-side,” as historian Bruce Schulman put it.

The Carter administration’s priorities devastated the Democratic coalition. While Reagan and his allies were busy integrating the Goldwaterite grassroots right into the GOP establishment during the 1970s, Carter and likeminded Democrats kept at arm’s length a vibrant ’70s grassroots left that included a revived labor movement, growing women’s and gay and lesbian right’s groups, and a bevy of new multi-issue organizations, such as ACORN, Common Cause, and Public Citizen. Nonetheless, when Reagan defeated Carter, neolibs blamed Carter’s alleged liberalism.

Whatever the Reagan Revolution’s deleterious effects on Democrats’ fortunes at the ballot box, the party’s time in the presidential wilderness provided neoliberals with the perfect opportunity to stage a bloodless coup in the Democratic Party. In the mid-1980s, Alvin From, a staffer for a series of moderate Democrats, recruited Al Gore and other neolibs to form the Democratic Leadership Council. The nascent DLC argued that the defeat of Carter’s former vice president, Walter Mondale, in 1984 further demonstrated the failure of McGovernism, despite the fact that Mondale’s platform of deficit-slashing “New Realism” actually marked the party’s continued shift to the right.

Emboldened by Reagan’s reelection, the DLC quickly attracted dozens of almost exclusively white male elected Democrats to its ranks, as well as buckets of seed money from some of the largest corporations in the country, including Morgan Stanley, Dow Chemical, Citigroup, and Koch Industries. Preferring the term “New Democrats” to “neoliberals,” the DLC’s adherents kept the neolibs’ pro-business orientation and appended an even more reactionary stance on social and cultural issues. The New Democrats, as the DLC’s Chair Chuck Robb said, were no longer afraid to speak “uncomfortable truths” about black poverty, “[I]t’s time to shift the primary focus from racism—the traditional enemy without—to self-defeating patterns of behavior—the new enemy within.”

The DLC’s combination of fealty to big business and criticism of the poor earned denunciations from activists and intellectuals like Ralph Nader, Arthur Schlesinger, and Jesse Jackson, who dubbed the DLC “Democrats for the Leisure Class.” Even McGovern himself felt the need to weigh in on the party’s drift to the right. Writing in The Washington Post, McGovern noted that most Americans had seen their incomes stagnate since the 1970s, while the rich had seen their incomes soar. “As matters now stand, the government deck is stacked in favor of the well-connected against ordinary Americans—on taxes, on government largess, and on the impact of the federal budget,” McGovern wrote. When Democrats tout the virtues of economic growth “their words ring hollow to most Americans,” McGovern continued. “Growth continues to be concentrated at the top—not among those in the middle or below.” The logical conclusion, according to McGovern, was that “the Democratic Party has lost the confidence of the American people, not because it is too liberal, but because it has neither kept faith with the historic values of liberalism nor defended those values to the public.”

But the DLC had the institutional and financial firepower to slough off these criticisms and bend the political narrative to its liking. In the hands of the DLC, even the loss of neoliberal poster boy Dukakis to George H.W. Bush in the 1988 presidential contest somehow further demonstrated the bankruptcy of big-government liberalism.

Ultimately, Bill Clinton became the only Democratic presidential candidate to live up to the New Democrats’ ever-shifting standards. How did Clinton do it? He won. The 1992 campaign run by Clinton and fellow DLCer Al Gore contained an odd mélange of neoliberal pieties and populist economics. At the same time that Clinton-Gore campaign commercials claimed they rejected “the old tax-and-spend politics,” Clinton and Gore were running on a platform promising tens of billions of dollars in new infrastructure and education spending, national health insurance, and a tax overhaul that not only called for redistributing the burden from the poor and middle-class to the rich but was sold in Clinton-Gore campaign materials using an echo of McGovern’s anti-inequality rhetoric.

However, the economic populism promised by Clinton in the 1992 campaign withered in office as DLC members assumed key policy roles in the Clinton White House. Following an unsuccessful effort to institute his privatized form of national health insurance, Clinton lurched further the the right, hiring DLC-pproved strategists Mark Penn and Dick Morris, who helped Clinton “triangulate” his subsequent policies between the poles of an increasingly radical Republican Party and an increasingly conservative Democratic Party. The result, to no one’s surprise, was a series of legislative accomplishments that looked as if they had been ripped from the GOP’s legislative wish list, including the North American Free Trade Agreement, “the end of welfare as we know it,” the Defense of Marriage Act, financial deregulation, and yet another top-heavy capital gains tax cut.

But just as the New Democrats’ neoliberal ideology was becoming firmly entrenched as the Democratic Party’s dominant philosophy, it began to falter electorally. Al Gore followed in Clinton’s footsteps in 2000, but this time the neoliberal playbook failed. It failed again in 2004 when Democratic primary voters nominated New Democrat John Kerry. In 2008, the DLC and most New Democrats favored Hillary Clinton, but the group also indicated it would support Obama. Yet when Obama defeated John McCain in the general election, more than a few commentators noted both that Obama’s coalition looked a lot like McGovern’s and that the GOP’s attempts to turn Obama into a McGovernesque, weak-on-defense socialist failed. Moreover, during Obama’s first term, the Democratic Party broke a cardinal DLC rule by shifting to the left on social issues such as gay marriage, albeit only in response to the diligent work of grassroots activists to move public opinion to the left first.

Yet, the neoliberal critique of McGovernism refused to die. Neolibs associated with the DLC and its spiritual successor, the Wall Street-backed Third Way, have spent the last four years hammering away at Democrats’ flirtation with economic populism. By 2012, the neolibs had soured on Obama, predicting erroneously that Obama’s Bain Capital-slandering, tax-the-rich populist campaign against Mitt Romney would fail. The subsequent rise of the inequality-bashing, tax-hiking, Social Security-praising, “catastrophically anti-business” Bernie Sanders/Elizabeth Warren wing of the party has left neolibs positively apoplectic. If Sanders won the 2016 nomination, former White House Chief of Staff and JP Morgan Chase executive Bill Daley declared at a Third Way event, “You would be back to 1972.… [I]t is a recipe for disaster.”

In reality, neoliberalism was based on an electoral myth.

Any Democratic nominee was doomed in 1972. Modern election forecasting models based on variables like the state of the economy and the incumbent’s approval ratings make clear, in retrospect, that Nixon was destined to win in a landslide. Taking any guesswork out of the result, Nixon stoked the economy with expansive fiscal and monetary policy, and when polls showed that the public preferred McGovern on issues like inflation and taxes, Nixon shifted to the left. He took the unprecedented step of instituting wage-price controls to clamp down on inflation and promised to sock it to the rich and slash tax rates on the working class if reelected. “The essence of this is redistribution,” Nixon’s top domestic adviser, John Ehrlichman, told an astonished press. On foreign affairs, Nixon could justifiably claim that he was not only winding down the war in Vietnam, but also cooling off the Cold War, thanks to his famous trip to China. The Democrats could have resurrected FDR and Nixon would have trounced him in 1972.

The neoliberals’ decades-long mantra that McGovern’s radicalism was to blame for Nixon’s victory, then, is squarely at odds with the reality of the 1972 election. More significantly, this mistaken analysis has obscured the ways in which McGovern’s campaign strategies and policies anticipated the political environment of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

It’s hard to view the demographic trends of both the Democratic Party’s electoral coalition and the country as a whole as anything other than “George McGovern’s Revenge.” The U.S. is well on its way to becoming majority nonwhite, while the support of people of color, women, and gays and lesbians—the political alliance mocked by conservative Democrats at the ’72 convention—have become crucial to the victory of any Democratic candidate. Likewise, it’s clear in retrospect that the seemingly quixotic appeal of McGovernism to white-collar workers was part of a longer trend in both the composition of the American workforce and the Democratic coalition. Whereas many at the time assumed that social liberalism was the only factor attracting white-collar workers to McGovern, the continued “proletarianization” of many service-sector workers makes clear in retrospect that McGovern’s economic populism was key, too.

From the vantage point of 2016, McGovern’s message on economic inequality and the political power of the rich seems prophetic. In the decades following McGovern’s loss, economic inequality continued to increase, economic uncertainty for most Americans grew, and real incomes and wages for moderate-income households and workers rose sluggishly, at best. Economic growth, which neolibs are still urging Democrats to emphasize above income distribution, has accrued almost wholly at the top, while the federal tax-and-transfer system actually did less at the turn of the twenty-first century to counteract inequality than it did in the late 1970s. Not coincidentally, recent research has demonstrated that the preferences of the rich almost wholly determine the direction of American economic policymaking.

The Democrats’ post-’72 turn away from McGovernism towards neoliberalism ensured that the party was poorly positioned to counter these trends. On the contrary, the New Democrats’ agenda of “free trade” deals, supply-side tax cuts, and financial deregulation actually served to make inequality worse, while the New Democrats’ welfare “reforms” increased the number of Americans in deep poverty. Even when well-meaning, the neoliberals’ incrementalist agenda of targeted tax credits and regulatory “nudges” actually damaged the Democratic Party’s image as the party of average Americans and fostered the anti-government attitude that aids the GOP. Unlike the New Deal’s universal programs or McGovern’s proposals for single-payer healthcare and the Demogrant, the neoliberals’ small-bore tax credits render invisible government benefits for the middle-class, such as subsidies for home ownership and education, leading many middle-income taxpayers to mistakenly believe the state’s only purpose is to funnel money to the allegedly undeserving poor and the unquestionably undeserving rich. Moreover, each tax credit, nudge, and Obamacare-style public-private Rube Goldberg device only only adds to the complex “kludgeocracy” of American policy, which itself fosters cynicism about the effectiveness of the government.

In contrast, McGovern’s calls for loophole-closing tax reform, proposal to use federal aid to curb hikes in regressive state and local taxes, support for payroll tax-funded single-payer healthcare, and Demogrant plan all would have done much to combat inequality. Moreover, contrary to neolibs’ insistence that McGovern’s platform was little more than warmed-over big government liberalism, proposals like the Demogrant actually contained more than a little tinge of libertarianism, thanks to the simplicity of cutting every American a check, rather than forcing them to navigate a complex bureaucracy. In an odd twist of fate, the very tech-sector entrepreneurs that the anti-McGovern neoliberals were attempting to woo are now suddenly infatuated with the idea of a Demogrant-like guaranteed income as a solution to inequality and poverty in the “gig economy” era.

Considering the lowly status of the Democratic Party today and the problems facing the country after decades of New Democratic philosophy, maybe it’s time for Democrats to abandon neoliberalism and try a little McGovernism.

This year, Bernie Sanders is the closest thing the Democrats have to McGovern, though not because Sanders is a sure loser. Sanders’s attention to economic inequality and stinging denunciations of plutocrats not only echo McGovern’s rhetoric in 1972, they also speak to the concerns of average Americans, who are increasingly worried about inequality and income stagnation. The Vermont senator’s platform of progressive tax redistribution and single-payer healthcare is undeniably popular and shares much in common with McGovern’s own proposals. Likewise, Sanders’s political strategy of energizing young and working-class voters and soliciting large numbers of small donations is McGovernism at its best. However, whereas a key demonstration of McGovern’s viability was his late-primary success in convincing African Americans to abandon Hubert Humphrey, Sanders has not yet had success wooing black voters away from Hillary Clinton, a shortcoming that may ultimately decide the fate of his candidacy.

But whether it’s carried by Sanders this year or a candidate like Elizabeth Warren or Keith Ellison in a future election, both demographic trends and the political realities of rising inequality suggest that a McGovernesque message of economic populism and social liberalism represents the future of the Democratic Party.

Though Democratic leaders and pundits are fretting about the “electability” of a candidate with a message like Sanders’s, the same realities that faced McGovern in 1972 will face any Democrat in November. Most of the factors that will determine the fate of the Democratic candidate in the general election—particularly the state of the economy and Obama’s approval ratings—are out of the nominee’s control. Moreover, little ink has been spilled and few hands have been wrung over how the relationship between economic growth and the popular vote, once the key to an incumbent party’s reelection, might be breaking down thanks to the inequality that the New Democrats have done so little to combat. While Obama’s record on job creation and economic growth is impressive, it hasn’t translated into rising wages for most Americans.

Despite this, the echoes of neoliberalism’s past in the Democratic Party establishment’s denunciations of Sanders’s candidacy suggest that if the Democratic nominee loses this fall, the explanation offered by party leaders and mainstream pundits will be the same one that has been trotted out after every Democratic defeat since 1972. If Sanders wins the nomination and loses in the general, it will be because the public wouldn’t stand for Sanders’s populist radicalism, and if Hillary wins the nomination and loses in the general, it will be because Sanders damaged her centrist credentials in the primary by pulling her too far to the left.

In other words, it will be because of McGovernism.