In the last weeks of the summer of 1882, as she was preparing to leave Baden-Baden for London (then Paris, then Florence), Constance Fenimore Woolson wrote Henry James that “there never was a woman so ill-fitted to do without a home as I am.” She was, according to her biographer Lyndall Gordon, “‘nervous’ and homesick, hauling her memorabilia and the spoils of travel from place to place.” Her items included:

her tear vase

her collection of ferns

a picture of yellow Jessamine (her favorite flower)

a weighing machine

a stiletto from Mentone

etchings of Bellosguardo and a red transparent screen used there

a 1760 edition of the poems of Vittoria Colonna

seven old prints bought by [her great-uncle James Fenimore] Cooper in Italy which a cousin had given her together with the original contract between Cooper and his publisher, G.P. Putnam Sons

an engraving of Cooper

a copper warming-pan from Otsego Hall given to her by one of Cooper’s daughters, Mrs. Phinney

and a photograph of her cherished niece, Clare, which she hung in every room she occupied

This image of Woolson, turtle-like, carrying a heavy home on her back is both appropriate and misleading. “Fenimore,” as James familiarly called her, could be acutely nostalgic in some moods and, in others, as adventuresome as her namesake. Although she spent most of her working life in Europe, no places are evoked so consistently across her fiction as the Great Lakes region and the American South. Her characters are stubborn individualists and intrepid explorers, always venturing into uncharted territory or navigating natural wildernesses.

She had horror of daintiness. In her prose, she aspired to a style muscular enough to impress itself on a reader, flexible enough to turn on a dime from domestic scenes to shipwrecks or chase sequences, and sturdy enough to bear transplanting to different settings and situations. For James, fiction was a house; for Woolson, it was closer to a well-stocked tent, bulging slightly with keepsakes and mementos but ready to be picked up at a minute’s notice.

In recent decades, Woolson has been the object of a lively tug-of-war among scholars and critics, although this has not been the kind of attention, it’s safe to assume, that she would have hoped for. The contradictions of her life and the circumstances of her violent death—in 1894, she jumped from the three-story window of her Venice apartment—have been studied primarily for what they suggest about James: whether he belittled or respected her abilities; whether he refused her subtle advances; whether he privately acknowledged her severe depression; whether his lack of attention hastened her death. In her influential triple biography of James, Woolson, and Minny Temple, Gordon accused the male novelist of masking his own complicity in Woolson’s suicide by widely spreading misleading accounts of her “perversity” and dementia. (“She was not, she was never, wholly sane,” James wrote one of their close mutual friends, the composer Francis Boott, after Woolson’s death: “I mean her liability to suffering was the doom of mental disease.”)

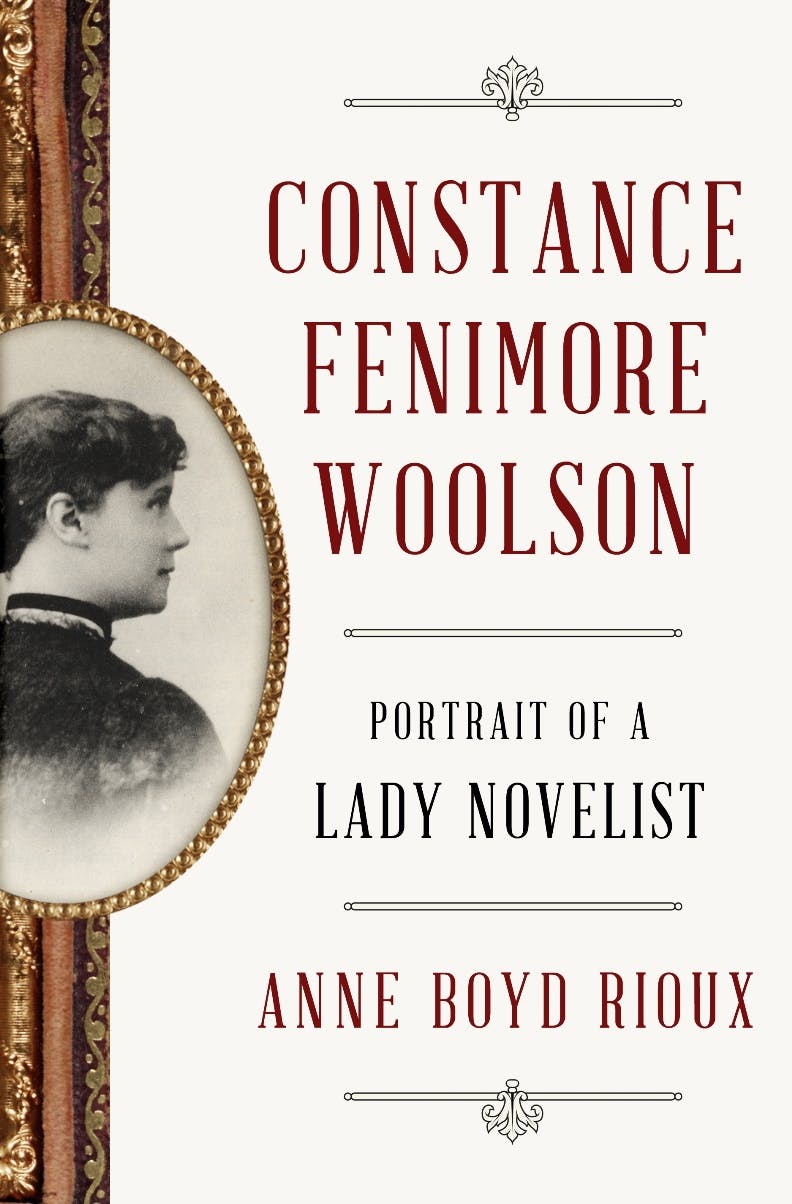

Woolson’s wholly secondary status in current American literary studies would have seemed strange to her contemporaries. As Rioux points out in Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist, her new biography of Woolson, Woolson was herself widely studied and critically celebrated in nineteenth century America. Rioux sees Woolson as the novelist Isabel Archer might have become had she inherited “the ambition of her creator, with the desire not simply to make her life a work of art but to make art from her life.” Yet even Woolson’s champions tend to emphasize her ambition, rather than celebrating the works themselves. What are Woolson’s books actually like? Did she write as she traveled, with inspiring boldness but heavy, dragging steps? Or did her fiction—five novels and dozens of stories produced over a period of 25 years—measure up to her own high standards?

By 1869, when she submitted the first portfolio of her stories and travel essays for publication in Harper’s, Woolson had lived through a series of disasters. In the month immediately after her birth in 1940, three of her siblings died of scarlet fever. The next years brought a sister—Emma Alida, who died barely after her first birthday—and a brother, Charlie, who would commit suicide in 1883 after a long series of mental breakdowns. In 1852, her 18-year-old sister Emma came down with symptoms of consumption and died a few months later; Georgiana, the first-born of the Woolson siblings, succumbed to the same disease the following year.

Shortly after the Civil War reached Cleveland, Constance grew close to a stately Union solider named Zephaniah Spalding. They agreed on a secret engagement, and although she much later wrote that “it was only the glamor of the war that brought us together,” Woolson was understandably shaken when, rather than return to Cleveland at the end of his service, Zeph lingered in the South, then moved to Hawaii and eventually married a sugar heiress nine years her junior. By most accounts, her strongest early attachment was to her father Jarvis Charles Woolson, from whom she inherited a love of traveling (their excursions around the Great Lakes inspired many of her early stories and sketches), a predisposition to clinical depression, and a degenerative hearing condition that left her largely deaf by 30. It was Jarvis’s death in 1869, Rioux convincingly argues, that led Woolson to publish her work for the first time.

These early disasters help account

for the writing Woolson soon started to produce, which so often was bitter,

morbid, and severe. It also clarifies the impulses and ambitions behind the

first two books of fiction Woolson published under her own name, Castle Nowhere: Lake Country Sketches

(1875) and Rodman the Keeper: Southern

Sketches (1880). She began to accommodate more eccentric characters and

search out settings wilder, less civilized, or farther-flung. The central

figures in the stories collected in Castle

Nowhere include a doomsday prophet who lives among the crisscrossing channels

of a Lake Eerie marsh (“St. Clair Flats”), a coal miner who moonlights as a

painter in a secluded German village off the Tuscarawas River (“Solomon”), and

a community of hunters and trappers on a Lake Superior island (“The Lady of

Little Fishing”). In an 1875 letter, she insisted that her aversion to the

customary forms of women’s fiction—what she called “‘pretty,’ ‘sweet’

writing”—had led her to dare “a style that was ugly and bitter, provided it was

also strong.”

In the fall of 1873, Woolson relocated to St. Augustine, Florida, where she lived for six years between frequent reconnaissance trips across the Reconstruction-era South. The fiction she produced during that period, later collected in Rodman the Keeper, shows the limits of her sympathies. She could manage detailed, nonjudgmental portraits of penniless former plantation masters, but she came up against an imaginative wall when she wrote about the lives of black freedmen in Florida. The unnamed “little black” who visits the dignified title character in “Rodman the Keeper”—portrayed “whistling and shuffling along, gay as a lark… loitering by the way in the hot blaze”—is a typical caricature of the black servants and sharecroppers who populate many of her stories and novels. Undisciplined, lazy, and delighted at a gift of the smallest tossed coin, none of these characters have the depth of consciousness Woolson gives their former masters. The thinness with which Woolson imagined these characters is one of the most graceless ways her novels have aged.

Woolson met James in Florence midway through 1880, less than a year after her move to Europe. It was she who sought him out, a fact James was quick to note. “I see no one else of importance here,” he wrote his sister Alice about his time in Florence. “I have to call, for instance, on Constance Fenimore Woolson, who has been pursuing me throughout Europe with a letter of introduction from (of all people in the world!) Henrietta Pell-Clark.”

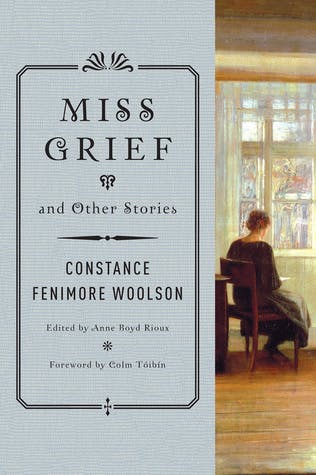

It’s not hard to imagine that James’s aloofness pulled Woolson into, as Rioux has it, a “crisis of confidence.” Between 1880 and 1882, she published a cluster of stories—“Miss Grief,” “The Street of the Hyacinth,” and “At the Chateau of Corinne”—in which young female writers and artists appeal to chilly older men to evaluate their work. These were worried stories, fantasies of judgment and rejection. They could only have been written by an author afraid of suffering the same verdicts their heroines receive. And yet, for the first half of the 1880s, Woolson’s work was anything but scorned or dismissed. In five years, she completed a bestselling novel about the travels of a young schoolteacher (Anne), a well-received long novella centered on an aging couple in a mountain town (For the Major) and an ambitious, sprawling fictional study of a spurned wife about which American critics were quarrelling eagerly (East Angels).

By December 1886, when they stayed for three weeks in nearly adjacent villas on Florence’s Bellosguardo hill, James and Woolson had become close mutual friends. Two months later, however, he delivered precisely the kind of judgment she’d dreaded receiving earlier that decade. Having been commissioned by Harper’s for a sequel to his article about William Dean Howells (Woolson’s former editor at the Atlantic), he wrote a survey of his friend’s fiction called “Miss Woolson.” Possibly worried about preserving their intimacy, James buried his doubts about her books behind layers of politeness and tact. His essay was full of respectful descriptive passages that nonetheless withhold full, enthusiastic assent, including the one Rioux praises for coming “close to the heart of her work”: “She is interested in general in secret histories, in the ‘inner life’ of the weak, the superfluous, the disappointed, the bereaved, the unmarried. She believes in personal renunciation, in its frequency as well as its beauty.”

Elsewhere, the essay’s coating of respect thinned. As James described it, Woolson’s belief in renunciation was linked to her “conservative feeling”—her unstated conviction that women had “been by their very nature already too much exposed.” Woolson had never said such a thing explicitly, but James remarked that “it would never occur to her to lend her voice to a plea for further exposure—for a revolution which should place her sex in the thick of the struggle for power.” The implication was that Woolson was always timidly receding as a fiction writer, restricting the moves available to her by narrowing her female characters’ range of possible choices.

Rioux writes that it “suggests [James’] great respect” for Woolson that the piece dwelt “on her work” rather than the details of her biography. But the features James actually attributed to Woolson’s books, as Gordon argued, often suggest a limited and self-declaredly minor writer, gifted chiefly at traditionally slight, womanly virtues like “evoking a local tone.” When Rioux decides that “Woolson must have been pleased with the essay,” she’s pointedly objecting to Gordon’s insistence that the article was “a calculated betrayal”—a hit piece “insidiously concealed in afterthoughts” and gentle qualifications. Gordon might have been over-harsh on James (was he really being “insidious,” or just struggling not to wound an acquaintance whose works he didn’t deeply care for?), but Rioux finds more admiration for Woolson in the essay than James likely intended to convey. For Rioux, “the real betrayal” came when James published a harsher revised version of the essay in his 1888 book Partial Portraits, where he came out and said that he found Woolson’s fiction “characteristic of the feminine, as opposed to the masculine hand.” But his essentially critical view of Woolson’s writing can be felt nearly as strongly, if more subtly, in the original.

In at least one respect, Gordon and Rioux agree on what James wrote. Woolson’s fictions often do center on characters whose shared strength is for stubborn, private self-refusal, who suffer in silence, or whose impulse is to endure injustice rather than protest it: Margaret in East Angels, who denies herself the company of the man she loves out of obligation to her philandering, indifferent husband; Eve in the later novel Jupiter Lights, who repeatedly rejects a madly devoted suitor to keep him from knowing that she’s done his family an injury; Gertrude, the spinster in “In Sloane Street,” who nurses an unspoken love for her male friend yet lets his shallow wife control him.

Woolson played with fixing these stubborn, resigned characters at the center of her fictions and surrounding them with livelier, more adaptable figures capable of challenging their motives and resolve. Her sympathies, however, lay with characters whose self-abnegating wills couldn’t be bent. She led a chaste life (Rioux relates that she confessed being unable to “judge the much-revered statues” she saw in Italy “because she was so unacquainted with the human form”), and she often fretted over how to give her characters a powerful presence on the page despite their own chastity. In some cases she attempted to solve this problem by intensifying the tone of her narration, as if to compensate for her characters’ reduced charisma on the page. The effect could be sermon-like, as in a late scene from East Angels:

Only that Unseen Presence who knows all our secrets, our pitiful, aching secrets—only this Counselor heard Margaret that night… The torturing longing love, the misery, the relapses into sullen rebellion, and then the slow, slow return towards self-control again, all these it beheld with pity the most tender. For it knew that this was the last struggle, it knew that this woman, though torn and crushed, would in the end come out on the side of right—that strange hard bitter right, which, were this world all, would be plainly wrong.

It was passages like these, one can imagine, that gave James pause when he read Woolson. Coming across them, you start to understand why Woolson’s advocates stake their arguments on her personality and independence more often than on excerpts from her prose. Situated where it is in East Angels, the passage just quoted seems almost justified in its solemnity; excerpted, it sounds embarrassing (“with pity the most tender”).

Above all, passages like this suggest what a dangerous business it is to pit Woolson against James—a quarrel Harper’s started in 1887 and that Rioux misguidedly re-ignites in Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist. Her comparisons between Woolson and James are this otherwise scrupulous book’s weakest passages. They depend on patently unfair dichotomies: that Woolson believed “fiction should appeal foremost to the heart and soul… and only secondly to the head and the ear” (as if James thought otherwise); or that, “while James had brilliantly dissected his characters’ consciousness, Woolson was after their hearts as well, believing the drama of inner life incomplete without a close examination of characters’ emotional states” (as if James thought it would be).

However Woolson reacted to the February 1887 version of “Miss Woolson,” she kept up relations with James. They reunited at Bellosquardo that April, this time living in separate apartments under the same roof. There has been much speculation about this arrangement between two people so private—one hiding his sexuality; the other her tendency toward depression—but James and Woolson were hardly alone.

A constant stream of expatriate English guests poured in and out of Woolson and James’s villa—a five-minute walk away from Francis Boott’s. After the sudden death of Boott’s daughter Lizzie the following year, Woolson and the bereaved father began a long, unbroken correspondence. Over the next several years, Rioux shows, Boott and several other older men—the kindly scholar Willard Fiske, who surprised her with gifts of trinkets and maple sugar; the Harper’s editor Henry Mills Alden—joined James as Woolson’s confidantes, and her letters to them from this time give evidence of her worsening depression. A short trip to Cairo lightened what James would later call her “mental disease” but failed to cure it. “Did you ever,” Woolson asked Alden in a letter from 1890,

see a small insect, trying to climb a wall, and always, sooner or later falling to the floor—only to begin again? That is I. If the cruelties do not happen to me personally (though many of them have happened, and continue to do so), they happen to some one within my sight; and then down I go again mentally, overwhelmed by the view of so much dreadful, & helpless, & often innocent (or comparatively innocent) suffering. I can’t get over it.

This was not a kind of thinking James could comfortably confront. In the last years of Woolson’s life, their relationship came to resemble something other than a professional rivalry; it was a friendship between a depressed person and someone too withdrawn to give adequate comfort. Writing that Woolson’s Southern fictions give “on the whole … a picture of dreariness—of impressions that may have been gathered in the course of lonely afternoon walks at the end of hot days” was James’s way of confessing the deep reserves of failure, gloom, and pessimistic resignation he’d seen in them, and in their author.

How were such feelings to be handled? James’s own novels are intricate patterns of intentions hidden and disclosed, secrets withheld, desires transfigured, and weaknesses manipulated. Nothing about them suggests that their author would have understood the dreary, deadening sensation of “going down mentally,” and he admitted as much. “I don’t know why we live,” he wrote Grace Norton in 1883, “but I believe we can go on living for the reason that (always of course up to a certain point) life is the most valuable thing we know anything about, and it is therefore presumptively a great mistake to surrender it while there is any yet left in the cup.”

The difficulties James encountered with Woolson’s fiction present themselves just as strongly to anyone who reads her novels and stories today. They can be dreary objects. Their feisty, colorful characters seem somehow unformed—friendly diversions from the tougher-skinned, more reserved heroines who usually stay planted at the center of the action. Resignation, stubbornness, fixity: these are unreliable and inefficient energy sources for the dramatic movement of a book. That Woolson kept returning to these subjects and at the same time concealing them—dressing up her fictions with chase scenes, rescue missions, violent encounters, and sermonic interior monologues—makes reading her novels feel like prying into the consciousness of a private person set on not letting her own sufferings show. It’s an experience at once as unhappy and as haunting as the story of Woolson’s life.