Here’s a little experiment my partner and I have been running for the last five years: We go to a restaurant with table service. He orders, say, the squash risotto, being a vegetarian. I, a murderous omnivore, order the pork chop. Then we sit back to see how often we end up switching plates when our server returns.

We haven’t kept official records, but I’d say I’m handed the squash roughly 85 percent of the time (excepting extremely fine dining, where I’m fairly sure you’re taken out back and force-fed McNuggets should you make such an error). I don’t blame the hard-working people bringing me my food. They’re busy juggling multiple tables, and, in the majority of cases, their instinct probably would have been right; in my years working in the food service industry, I’m certain I made the same gamble. If you have to guess, you assume the hunk of protein is for the dude.

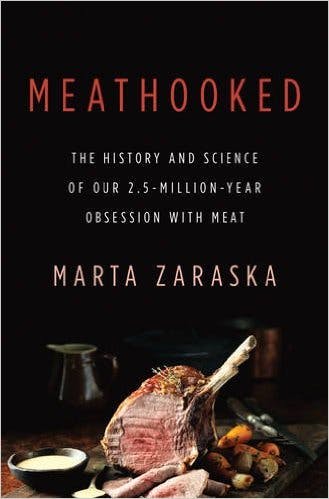

Why does the consumption of animal flesh strike us as somehow inherently masculine? As journalist Marta Zaraska explains in Meathooked: The History and Science of Our 2.5-Million-Year Obsession With Meat, it’s complicated. For one thing, the advertising industry gives full credence to this idea. To give just one of Zaraska’s examples: A pre-economic crash Hummer commercial showed a man, having just been shamed at the grocery store for buying tofu and carrots, heading off to buy the massive vehicle. The tagline then appears: “Restore the balance.” In case that was too subtle for you, the original line was, “Restore your manhood.”

These ads spring in part from traditions and symbols that stretch back millennia. Big pieces of grilled meat—which cannot be made from the tough, cheaper parts of an animal—have long been associated with abundance, unlike the stringy, chewy bits that were available for the poor and were braised for hours until tender by women. As Zaraska writes, “Thus grilling became associated with wealth and with celebrations, and that is also why grilling is for guys and stooping over a pot of stew is for women—the first one is prestigious, the second one is not.”

And there’s the fact that my partner is over a foot taller than I am; due to some unfortunate nineteenth-century bunk science, conventional wisdom holds that a person of such stature would need vast amounts of protein to have achieved that height. In other words, at play in that snap decision is an international meat industry worth billions, a lifetime of advertising, millennia of tradition, deep-rooted cultural symbolism, and decades of misunderstood science. And that goes into not just this decision, but millions of others as people around the world choose, over and over again, to eat meat.

There have been many books that tackle meat consumption released over the last decade. One of the most famous examples is Michael Pollan’s perennially referenced Omnivore’s Dilemma, which focused on moderation and consideration for the animal’s welfare. And from the wracked-with-guilt aisle, there’s Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals. (Sample quote: “Not responding is a response—we are equally responsible for what we don’t do. In the case of animal slaughter, to throw your hands in the air is to wrap your fingers around a knife handle.”) Where these books focus on whether we should eat meat, Zaraska is interested in why we still have the desire to eat meat, especially when we are flooded with so much information on how deleterious meat is on our health, our environment, and on the animals themselves. Why is meat so important for so many of us that we compromise our own well-being to eat it?

This is no small question. According to Zaraska, Americans eat 275 pounds of meat per person each year; 24 million U.S. farm animals are slaughtered every day. Between 2013 and 2014, India’s beef shipments rose 31 percent, making it the second-largest beef exporter in the world. By 2030, China will consume 22,050,000 pounds more pork. Across much of the world, even in societies that were traditionally vegetarian, meat consumption climbs steadily.

Some would argue this is due to the fact that humans were biologically designed to eat flesh. Yes, we have canine teeth but, as Zaraska notes, we lack the teeth and specialized muscles true carnivores use to chew through a dead caribou without use of tools. Humans are, instead, the consummate opportunists: When given the chance to eat meat, by scavenging or, later, through the invention of tools, we took it. It was ingenuity, not destiny, that led us to meat.

This switch to regular meat consumption around 2.5 million years ago has had a profound impact on humans. Over time, this caloric bonanza shortened our digestive tract and expanded our mental capacities, not only by giving us larger brains, but also by pushing people into complex societies in order to allow them to hunt effectively. Freed from spending entire days churning through grass for the barest nutritional payoff, we learned to cooperate, compete, and share.

However, while it may have given us an evolutionary boost at one point, to conclude from this history that we should pursue the meat-heavy diet advocated by Paleo adherents is foolhardy, Zaraska argues. “Rather than dumping peanut butter and potatoes down the drain, we should take another lesson from our Paleo (and earlier) ancestors: instead of looking for a perfect and ‘natural’ diet from the past, start looking for one that would be best for right here and right now,” she writes. The meat we eat is different meat, fattier thanks to domestication. The world we inhabit is a different world, the lives we lead are different lives. Can’t we get over the flesh-eating already?

Not easily, writes Zaraska. Like any addiction, this one has more than one hook in the human psyche. To describe the meat industry as “big” is the height of understatement: In 2011, U.S. meat sales were worth $186 billion. As Zaraska points out, that’s more than the GDP of Hungary. Big businesses produce strong lobbying groups, which keep billions in subsidies flowing and tamp down efforts to change, for example, the U.S. Dietary Guidelines. And then we get to the advertising. During the five years following the rollout of the pork industry’s ubiquitous “The Other White Meat” campaign in 1987, pork sales rose 20 percent. In 2011, McDonald’s, a leading global beef buyer, spent $1.37 billion on advertising. Whatever else you might be doing, you’re probably also lovin’ it.

But meat consumption cannot be chalked up entirely to corporate sloganeering; it’s not as though Big Capon was foisting their product on the seventeenth century ruling classes. For one, meat tastes good. The Maillard reaction, in which amino acids and sugars recombine to give meat that delightful seared brown color, as well as the joys of fat and umami, are no joke, and there are many reasons why we and our distant ancestors have found delight in roasted meat. (Zaraska explains the finer points of this deliciousness in some detail, delving into the world of umami—the “meaty” or “full” flavor sensation that can come from foods such as meat, mushrooms, or some cheese—which chefs harness into combinations sometimes called “u-bombs.”) But it’s her examination of the role of culture and tradition that resonates most deeply; from the tastes we absorb as fetuses to subtle clues from our parents, we are attuned to society’s preferences, and for centuries, lots of meat has meant wealth and power.

This, when combined with the incredible power of habit, can create an attitude toward meat that almost defies interrogation; as Zaraska’s own mother tells her, “I like meat, I eat meat.” Or to use a recent example, consider the World Health Organization’s announcement that processed meats can cause cancer. I heard countless people arguing that the report was overblown, that no one really eats that much bacon, that statistically, the chances are slim. Imagine if the WHO declared that eating broccoli could statistically increase your chance of developing cancer at all. Would you think, “What’s life without a little risk?” I imagine many, many Americans would instead be grateful that our long national cruciferous nightmare had ended.

For this reason, there’s little chance we’ll be living in a meatless world anytime soon. Many people can’t even reach the low bar of not throwing meat away. Most people want to fight climate change, live longer, stand against animal cruelty, and decrease antibiotics and other pollutants in the food system. But few actually take this simple concrete step that would help them accomplish all those things; according to Zaraska, just 3 to 5 percent of Americans are vegetarian. In the Western world, vegetarians are so few as to be what one expert describes as “a blip on the demographic radar.”

I am not one of their ranks; although I don’t eat meat often, I don’t eat it never, despite many efforts to stop. I tried to take comfort in Zaraska’s pragmatic argument that strict vegetarianism isn’t always necessary. As she writes, “Which saves more lives—one person stopping eating meat altogether or millions cutting out just one meat-based meal a month?” However, that is just one in a long line of justifications I’ve used over the years to allow myself one more Thanksgiving turkey, one final barbeque. People have, after all, been honing strategies for avoiding dealing plainly with the facts of our carnivorous behavior for centuries.

“At the end of the day, despite the many complex reasons rooted in evolution, history, and culture, the most basic reason would be: because we can,” Zaraska admits. We are still opportunists, and the opportunities for consuming flesh have multiplied. The statement carries with it a certain existential fatalism: We are what we are, and what we are is animals who would eat ourselves to death. However, the book does not end on quite such a pessimistic note. While, for the litany of reasons just discussed, humanity is not headed toward a meat-free future anytime soon, the realities of climate change and a growing global population will eventually make the choice for us. The earth simply does not have the resources to support current rates of meat eating in the future. We will have to accept lab-grown meat, or plant-based meat substitutes, or just embrace the subtle pleasures of a bowl of beans and rice.

In order to get there before the end of days, we must take the hardest step of all: admitting we have a problem and changing our thinking about the issue. Whatever biological imperative pushed our ancestors to eat meat, we can walk away from it. We can break our habits and change our values; we are free to use those big brains meat may have granted us to make decisions our ancestors might not understand but our progeny will certainly appreciate.

Zaraska hopes that by embracing meat substitutes as desirable, not just necessary, we can begin to break the stranglehold meat has on humanity, although she admits this will be a long and rocky adjustment. I’m not entirely hopeless, however: Just a few blocks from where I live, a burger joint opened last summer. When I walk by in the evenings, there is almost always a line trailing down the block. It was reviewed by the New York Times and no less an authority on men’s contemporary culture than GQ named it the best burger of the year. And the restaurant is entirely vegetarian. The burgers are crafted of nuts and quinoa and other plant-based foods, and yet they are surrounded by a halo of hype. People love tradition and habit, but there’s something else they love as well: the opportunity to try something new.