David Kaczynski’s story would make a very good contemporary realist novel. It has all the important elements: complex family dynamics, suicide, mental illness, famous political violence, and a terrible choice. Kaczynski shares his last name and his parents with Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, who mailed bombs to universities and airlines between 1978 and 1995, killing three people and wounding 23. David was the one who turned Ted in to the FBI, and then fought to keep him out of the death chamber. Twenty years later David has written a book about the experience, but the plot is the only thing Every Last Tie shares with fiction.

If a novelist wrote this story, David would be the well-adjusted, loving brother, unable to comprehend what has happened to Ted, who—secluded in a Montana cabin—was trying to terrorize American society by mailing explosives to seemingly arbitrary targets. David’s choice to turn Ted in would be painful, yes, but practical, serving as a critique of zealotry and myopic ideological devotion. It would be easy to frame David’s central conflict as a choice between family commitment and obedience to the law, like Antigone if she went the other way.

Except David, too, is non-conforming. He’s a committed ideologue, though to Buddhism and not his brother’s insurrectionary primitivism—in 2012 David was appointed the executive director of Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, a monastery in Woodstock, New York. He has a tendency to wander in the desert alone for extended amounts of time, and he concedes that his obsession with his wife Linda could have been considered pathological had she not eventually reciprocated and married him. In most families, David would have been the black sheep. But that’s not the way it turned out.

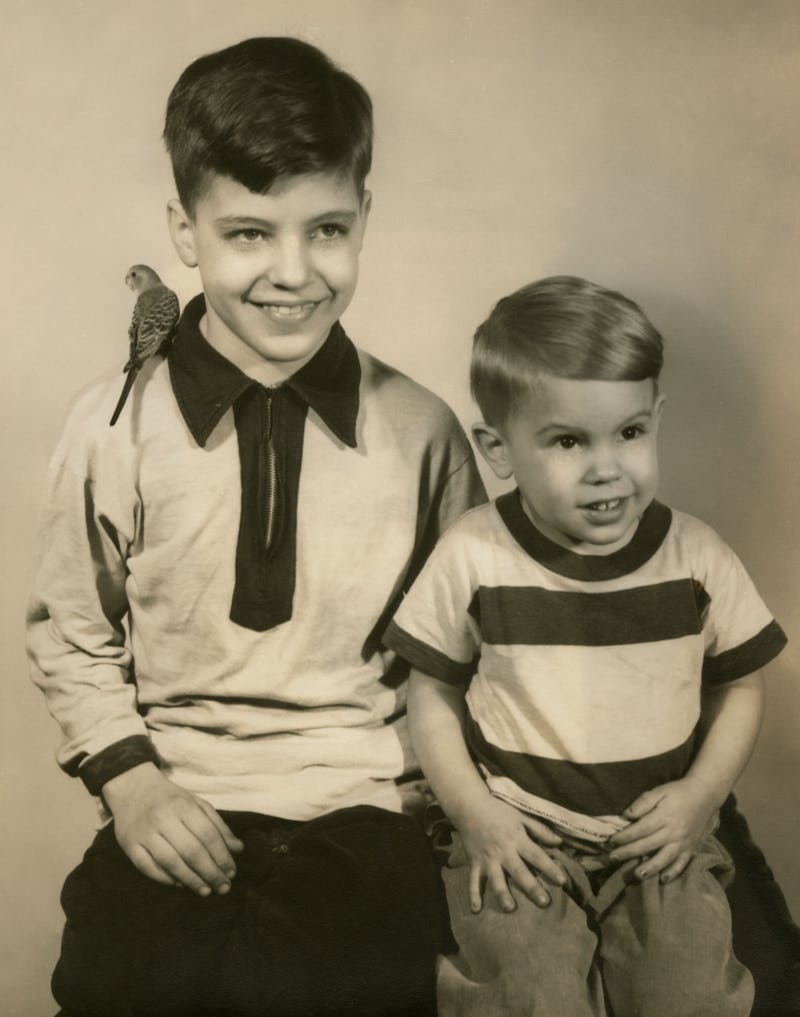

At just over 100 pages, Every Last Tie is a detailed story of family dynamics, a sort of participant ethnography of mid-century, white, suburban American domesticity. The Kaczynski brothers were born in the 1940s in Evergreen Park, Illinois. David describes his father Theodore Sr. as a “blue-collar intellectual” who made sausages for 30 years and took pride in being a local gadfly of the FDR-liberal variety. Their mother Wanda was a first-generation Polish-American who grew up in material and emotional hardship and worked to make sure her sons experienced neither. Together they encouraged their sons’ self-direction and in one generation went from blue-collar to Harvard and Columbia. It’s eerie how close the Kaczynskis were to the picture of the ideal mid-century American family.

David’s book is, in a way, the least helpful parenting guide of all time. Wanda and Theodore were by David’s account exceedingly good parents: good role models, present, engaged, affectionate, supportive. How could they have raised the Unabomber? On one level it points to what my own mother calls the “cherchez la mom” fallacy—children are not direct products of their parenting. If Ted’s young adult life had gone differently after he left home for Harvard at 16, it’s totally possible that Wanda Kaczynski might have spent her last years touring the morning shows dispensing expert advice on how to raise brilliant boys instead of coping with having birthed an infamous serial killer.

Throughout his recollections David evinces enormous compassion for his parents, both as Ted’s first victims and as people held—even after death—partially responsible for his brother’s actions. Ted blamed them first and foremost, accusing his parents of sacrificing his happiness for their vanity. David sees more psychosis than validity in Ted’s indictments, and he is himself evidence that his parents were at least as likely to raise a Buddhist leader as a terrorist. But that doesn’t mean the dynamics of his upwardly mobile suburban family are benign. He couldn’t possibly blame his parents for wanting their genius son to attend Harvard, but in retrospect it’s hard to imagine he wouldn’t have been better off at Oberlin, where he had also been accepted. They wanted what was best for Teddy, but they were trying to determine that in a world that was not interested in being careful with their son. David doesn’t try to assign blame so much as he’s trying to sketch a history of harm.

Take for instance, gender. As the Unabomber, Ted ranted about feminists, part of what David frames as a lifelong problem with women. “Feminists are desperately anxious to prove that women are as strong and as capable as men,” Ted wrote in his manifesto. “Clearly they are nagged by a fear that women may NOT be as strong and as capable as men.” Though he was far from a conservative, his complaints about “PC culture” became a touchstone for subsequent right-wing terrorists like Anders Breivik.

The Kaczynskis were probably better than average for their time and place when it came to educating their sons on how to treat women, but the nuclear family structure still inculcates a certain disregard for women’s ability to think. David remembers his mother telling him the story of Antigone, which she had recently finished reading, and his thinking that her reaction and the story were dumb. He convinced himself the characters could have avoided their situation with a little foresight. “I tried to be dismissive,” David writes, “Mom was a female given to emotional excess.” It took David a long time to understand his own feelings about his mom; what exactly that has to do with the particular valence of his brother’s aggression he leaves to the reader, but it seems to impact his telling of the story.

David is careful to stress that his wife Linda solved a case that no one else could figure out. Linda never met Ted, and even though he was an isolated shut-in there were many people who knew him better than she did. But Linda is able to see the extraordinary harm Ted has caused his family, and is able to make the leap from emotional cruelty to the physical attacks. And once she has the suspicion, Linda is able to convince David the right thing to do for everyone is to investigate it thoroughly and inform the authorities. In a back-of-the book summary of the narrative, David makes her role seem supporting, like the concerned wife in the AMC show who says out loud what her husband already knows. But David does his best to adjust our perspective and get us to understand the thinking required to suspect your estranged brother-in-law is the FBI’s most wanted, and the emotional intelligence necessary to purposefully act on those suspicions without destroying the people you love. Linda is more than a character; she gets her story, too.

Compassion isn’t a very popular critical methodology, but that’s unfortunate. David takes empathy extremely seriously, not just as a means to the end of forgiveness, but as a way of understanding the past. He goes through past moments, instants that stick out for what they meant about his relationships with his parents and his brother and their relationships with each other, how everyone must have felt. There’s no doubt that Ted’s violence adds weight and significance to certain of David’s memories, but their relatively normal childhood is the material he has at hand. If any of us found our families similarly ripped apart from within, where would we find meaning? David finds the violence in his home by looking for the hurt.

One of the heaviest moments in Every Last Tie has nothing ostensible to do with Ted. David tells the story of burying his parents’ ashes a couple years ago and feeling a deep need to apologize to both of them. To his mother, he apologized for failing as a boy and young man to recognize her intelligence because she was a woman. To his father, he apologized for a small incident when he was a young man. David came into his parents’ backyard and saw a goofy pinwheel nailed to the fence, and made some crack about it. His dad said it had just been a flight of fancy, and took it down. At his father’s graveside, that’s what David regrets, “stifling his light-hearted impulse.”

Later, David’s father kills himself, having been diagnosed with terminal cancer, five years before Ted was revealed and caught. There’s masculine pride to suicide in the face of a drawn-out death, and David understands his dad was attempting something like mercy for his surviving loved ones. But he also watched his mother search in vain for a note, a goodbye, some final sign of care besides a corpse and a gun. David notes of adolescent Ted that he “seemed to have more respect for rules than for the relationships they are designed to protect.” It’s a common affliction, and it’s the same misattribution of care that David was guilty of when he mocked his dad’s pinwheel.

It takes a fundamental belief in compassion for this small act of inconsideration to merit mention alongside Ted’s actions, but there’s a value to seeing the qualitative commonality in disparate acts of cruelty. This value is analytical—Every Last Tie is extraordinarily insightful—but also instructive. By analyzing his own capacity for causing pain, David brings his brother close enough to learn something from him.