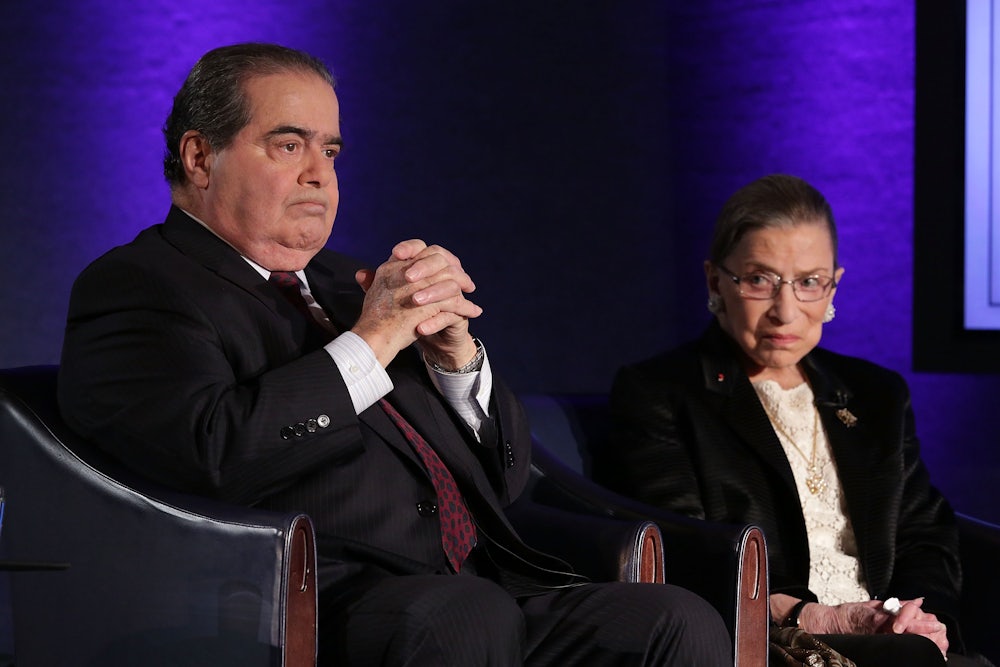

Justice Antonin Scalia left an indelible mark on American law. His prodigious intellect, distinctive style and sharp wit will be sorely missed by his family, friends and colleagues.

His passing also creates a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to shift the balance of power on the Supreme Court toward greater protection for the environment and greater access to the courts by those most affected by pollution and resource degradation.

A look at Scalia’s legacy reveals why his absence in the coming months could be a pivotal factor on environmental issues.

With few exceptions, such as his opinion in Whitman v. American Trucking upholding the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to set health-based air quality standards without regard to cost and his opinion in City of Chicago v. EDF rejecting industry arguments that coal ash isn’t a hazardous waste, Justice Scalia’s environmental legacy is decidedly negative.

Interpreting ‘standing’ and ‘harm’

He consistently voted in favor of property rights over protection of endangered species, wetlands and other natural resources. He dissented in the court’s landmark ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA that the Clean Air Act authorizes the agency to regulate the carbon pollution causing global warming and ocean acidification.

He wrote the majority opinion in a case limiting EPA’s authority to require pre-construction permits for new power plants that only emit greenhouse gases. He wrote the opinion overturning the mercury rule on a technicality—namely, that EPA should have considered cost as a threshold matter before even embarking on the rule-making instead of at the stage when the regulations were actually being applied to specific facilities.

He argued that the Clean Water Act should be narrowly construed to apply only to “relatively permanent bodies of water” rather than, as the lower courts had consistently ruled for over 30 years, to the entire tributary systems of the nation’s major waterways.

And he is the author of several decisions severely limiting the ability of environmental plaintiffs to challenge unlawful government actions. This includes Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, which the late Justice Blackmun in his dissent characterized as a “slash and burn expedition through the law of environmental standing.”

To establish standing, a plaintiff must show how it is injured by the action being challenged. Scalia applied a more liberal test of injury for industry plaintiffs than for environmental plaintiffs. Standing was presumed whenever industry alleged that a government action might cause undue economic harm but not when an environmental organization alleged that the same action would cause undue environmental harm.

Whither the Clean Power Plan?

Though President Obama has said he intends to nominate a successor “in due course,” Senate Republicans have vowed to stall the confirmation process in the hope that they will win the White House and have the opportunity to nominate someone more to their liking.

Suddenly the Supreme Court has become a huge prize in the 2016 elections, and, given the stakes involved, it is likely that the vacancy will remain well into 2017, and the court will be forced to make a number of difficult decisions with an evenly divided bench.

A split court has important implications in a number of key environmental cases.

Top of the list is the president’s Clean Power Plan (CPP), a rule that requires states to develop plans to lower carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. Only days before Scalia’s death, the court in a 5-4 party line vote blocked the rule’s implementation pending a decision by the D.C. Circuit, which has scheduled oral argument for June 2. The stay order provides that it will remain in effect until the Supreme Court either denies review (unlikely) or issues a final decision.

Most observers believe the government, arguing that the Clean Power Plan is legal, drew a favorable panel on the D.C. Circuit court, which includes Judge Sri Srinivasan, who is rumored to be on Obama’s short list of nominees.

Assuming Srinivasan remains on the panel, and further assuming the panel issues a decision this year upholding the CPP (not a forgone conclusion), there is a good chance the vacancy on the Supreme Court will not be filled by the time the case arrives there in 2017. This increases the odds of a 4-4 split, which would result in the DC Circuit decision being upheld, and the CPP dodging a bullet.

Clean Waters Act at court

Another case that may be affected by Scalia’s departure but with far less at stake is Hawkes v. Corps of Engineers.

The question presented is whether landowners can go to court immediately when the regulators make what is called a “jurisdictional determination” under the Clean Water Act finding—for example, that there are wetlands on the property that may require a permit to fill.

There is a clear conflict in the circuits on this question. The Eighth Circuit in Hawkes held that jurisdictional determinations were reviewable in court, whereas the Fifth Circuit in Belle Co v. Corps of Engineers ruled that they are not.

Interestingly enough, the disagreement rests on how to read Justice Scalia’s opinion in Sackett v. EPA. In that case, a compliance order under the Clean Water Act required restoration of an allegedly illegally filled wetland and exposed the recipient to potential penalties of $75,000 per day. Scalia ruled that the compliance order in this case is “final agency action” for which there is no adequate remedy in a court other than judicial review under the Administrative Procedure Act.

Another case being closely watched is the challenge to EPA’s Clean Water Rule that seeks to “clarify” the jurisdictional scope of the Clean Water Act and whether it covers tributaries that feed into waters protected by the act.

The need for clarification stems in large part from the Supreme Court’s decision in Rapanos v. United States, where the court split 4-1-4 and Justice Scalia authored a plurality opinion that would significantly reduce the scope of the act.

Justice Kennedy wrote a concurring opinion rejecting Scalia’s approach and establishing the so-called “significance nexus” test—requiring the government to prove that a wetland, alone or in combination with other wetlands in the watershed, plays an important role in protecting the quality of the water downstream and therefore is subject to the Clean Water Act. Because Kennedy’s significant test has been adopted by nine circuit courts as the controlling opinion from Rapanos, EPA used it as the basis for the Clean Water Rule.

The Sixth Circuit has stayed the rule pending its decision on whether it has exclusive authority to decide its legality. If the Sixth Circuit asserts jurisdiction, a final decision could be issued this year and the court would then be faced with another petition for review, knowing that it could result in yet another divided decision.

Finally there is a case involving the cleanup of Chesapeake Bay which is heavily polluted by agricultural runoff and other sources. The Third Circuit upheld EPA’s landmark cleanup plan in a case brought by the American Farm Bureau and joined by over two dozen states.

The issue presented is whether EPA exceeded it authority by developing a complex “pollution budget” and allocating responsibility for reducing the inputs of nitrogen and phosphorous throughout the eight states that comprise the basin. The conference on whether to grant review will be considered at the next conference which is scheduled for February 26. This will be the first test to see whether the post-Scalia court has the appetite to take up a case where there could be a 4-4 split.

With these and other environmental issues on the docket, the absence of Scalia will have a huge impact—as will the question of his eventual successor.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.