Dressed in white, twirling a parasol, or seated primly on a sofa, in the boudoir sequences of her “Formation” video Beyoncé reaches a century back into New Orleans history. The friends arrayed around her flutter their fans; one of them sips a cup of tea. Their lacy dresses and the damask wallpaper behind them, the thick curtains and framed pictures all evoke the heyday of Storyville, the first legally organized vice district in the country. We know what it looked like because of a set of portraits that a photographer named E. J. Bellocq took there in the 1910s, an era when reform-minded citizens were obsessing about sex work and state and federal police were beginning to crack down on it harshly.

The appreciations of “Formation” that

have poured in since the weekend have celebrated the video, and the Super Bowl

performance that followed, as political triumphs. Feminists have also hailed

Beyoncé for frankly embracing her sexuality. The Storyville sequences add

another layer to the history she is claiming as her own. They point to the story

of an elusive photographer, the haunting images he made, and the women who pose

in them—women who tried to gain economic independence through sex work and

often faced condescension and violence from the law.

Official paperwork simply called Storyville “The District,” but it came to be known by the name of the City Councilman who created it. After commissioning studies of Dutch and German red light zones, in 1897 Sidney Story passed a city ordinance setting up an area where prostitution and drug use would be permitted and monitored. It covered thirty-eight blocks in what is now Tremé. Women engaged in “vice” were required to reside within.

Located right next to the rail station, Storyville boomed. By 1900, it was the city’s largest revenue source; it soon became a thriving center of jazz, too. And it produced some legendary female entrepreneurs. Lulu White, one of the most famous madams in the district, ran a four-story “Octoroon Parlor” known as Mahogany Hall, where she employed 40 women at a time and regularly entertained the most powerful men in Louisiana. When the Army shut Storyville down, rumor had it that she lost $150,000 in real estate investments in the area, around $2.8 million today—a remarkable sum for a mixed race woman who had arrived with nothing to her name a decade earlier.

But during this period, middle class white Americans were seriously concerned about the sex trade. Most images that social workers and reformers produced of sex workers during the Storyville Era made them out to be depraved or pitiful, or both. In 1910, for instance, a German-American pastor based in Chicago named Frederick Martin Lehmann published a 418-page tome called White Slave Hell. Pages of glossy illustrations documented how ordinary women could fall into prostitution by accepting dinner dates. A series of photographs staged with actors show a male and female stranger meeting on the street, then canoodling tipsily in a restaurant. Next he pulls her—still laughing—by the elbow, into a door that has a sign on it, reading “Furnished Rooms.” “LED TO SHAME,” the caption laments.

Later, we see the young woman sobered up and sitting glumly behind what look like prison bars; then she languishes in a hospital. In the final panel, she has vanished, presumably dead. A crowd of nurses stare at the camera blankly above a couplet that sums up: “Vice brings her victims from the Red Light in,/ With bodies sick and soul all stained by sin.”

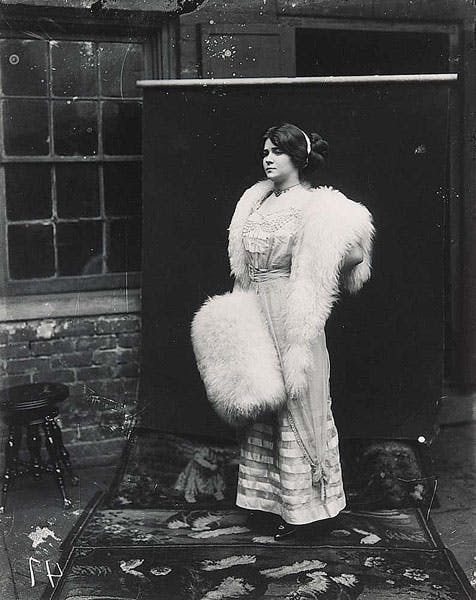

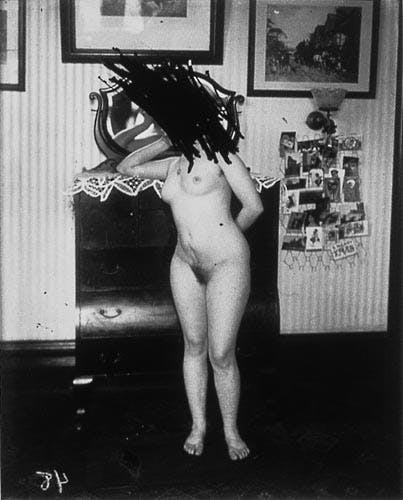

When E. J. Bellocq took his camera to Storyville, he saw something different. We know only a few things about Bellocq himself. Born into a wealthy white Creole family in 1873, he turned a youthful passion for photography into a career. He made a living documenting landmarks, steamships, and other machinery for a handful of local companies. But on his own time, he continued to take pictures of city life—visiting New Orleans brothels and opium dens.

When Bellocq died in 1949, his brother, a Jesuit priest, found 89 glass plates from the red light district in his desk—many of them cracked, scratched or corroded. None had been developed. In the late 1950s, the young photographer Lee Friedlander traveled to New Orleans to take his own photographs, and happened to learn about them. Over the next decade, Friedlander acquired them and made contact prints from Bellocq’s plates himself. Friedlander was so struck by the resulting images that he convinced the Museum of Modern Art to mount an exhibition.

In an essay she wrote to accompany a

book of prints from that show, which Random House republished in 1996, Susan

Sontag called them “unforgettable.” She muses that although the subjects were

prostitutes, the portraits were far from pornographic. “I

am a woman and, unlike many men who look at these pictures, find nothing

romantic about prostitution,” Sontag writes:

That part of the subject I do take pleasure in is the beauty and forthright presence of many of the women, photographed in homely circumstances that affirm both sensuality and domestic case, and the tangibleness of their vanished world. How touching, good natured, and respectful these pictures are.

It is not hard to see how Bellocq’s portraits might have appealed to Beyoncé and her team, too. “Formation” aims to transfigure familiar images from a long history of black American suffering into a celebration of Black Power and black possibility. These photographs express a wide range of lived experience and emotion. The women Bellocq captured may be poor, and their conditions may be sordid. But they do not look abject. Perhaps because we know so little about the intentions of the man who shot them, the women come alive as subjects, not victims. They assume playful poses in colorful stockings and frilly slips; they drink whiskey and play cards together; they fondle pets.

One woman, who appears in several portraits, looks away, proud in her upright posture. Another, in a dressing gown, slouches back, luxuriously pensive or bored. In this portrait, which the historian of prostitution Ruth Rosen borrowed for the cover of her classic study The Lost Sisterhood, another woman eyes her shot of whisky playfully. She does not seem especially eager to attract a customer. She is amusing herself. The strongest Storyville portraits flirt with the expectations of a voyeur. But ultimately, the reason for their staying power is that they capture their subjects’ dignity.

The women in these photographs appear to be white or mostly white. It is hard to know. Racist laws forbade black men from patronizing the Storyville brothels. But the government-issued “blue books” that advertised the “stock” and “services” on offer there demonstrate that a wide range of black, white, and mixed-race women all worked together on the premises. By choosing Storyville as one of the settings for “Formation,” the video evokes a long history of fascination with and exploitation of black female sexuality. The video seizes the classic site associated with the abuse of women—the brothel—a place that was used as a pretext to police and patronize them, and reclaims it as a source of power.