First, it’s important to ruin Finding Nemo for you. For if you wanted to tell the tale of a single father helping a young son grow into adulthood after the tragic death of his mother and siblings, clownfish are without a doubt the wrong animals to use. Marlin, for one, wouldn’t have been Coral’s only husband; as the dominant female clownfish of the anemone, she would have had several husbands (she also would have been significantly larger than Marlin or any of her other men, while we’re splitting scales). But, assuming that all of the other dads were killed along with Coral and the other kids, then Marlin, being the largest remaining male clownfish, would have done what any good father would have done: he would’ve changed his sex, becoming the dominant female. Clownfish, after all, are protandrous hermaphrodites, starting out male and later becoming female as the need arises. That would leave Nemo, formerly Marlin’s son, as the remaining male in the anemone, and once he was finally found, he’d be ready to assume the role of the new mate, becoming his former dad’s new husband.

If all this sounds off-putting, you might ask yourself why you expect clownfish to reaffirm your notions of father-son relationships in the first place. We look to the animal kingdom for assurance that how we love, how we fuck, and how we reproduce are somehow all normal—whatever “normal” might mean. In Amber Dee Parker and Hannah Segura’s 2013 conservative children’s book, God Made Dad and Mom, a young boy named Michael is confronted with the fact that a friend has two dads; after learning that God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve, Michael is taken by his father to the zoo, where, according to the publisher’s description, “he learns that animal families consist of a male, a female, and their offspring.”

The belief that in the animal kingdom, of all places, we’ll find affirmation of human hetero-normativity, suggests a strange anxiety, and one bound to lead to disappointment. It’s clear, after all, that young Michael didn’t hit the Central Park Zoo, home to the male chinstrap penguins Roy and Silo, who successfully fostered a penguin chick named Tango (the inspiration for the oft-banned And Tango Makes Three), but before you go celebrating penguins as a model of healthy tolerance and love, remember that naturalist George Murray Levick witnessed Antarctic penguins engaging in necrophilia while on Scott’s 1910 polar voyage. Levick was so shocked he recorded his findings in Ancient Greek so as not to disturb Victorian sensibilities, which meant they went unnoticed for over a century—a reminder of how far we’ll sometimes go to deny a natural world that doesn’t fit our expectations.

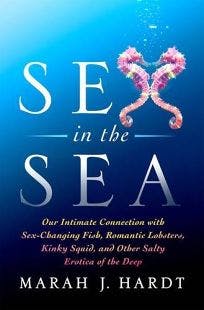

The story of clownfish incest and hermaphroditism is just one of many great stories of unexpected sex in Marah J. Hardt’s Sex in the Sea: Our Intimate Connection with Sex-Changing Fish, Romantic Lobsters, Kinky Squid, and Other Salty Erotica of the Deep. As its name promises, Hardt charts a course through the stranger and more exotic forms of mating and reproduction. From rays finding each other through magnetic charges, to whales with labyrinthine labia (whose purpose is still not fully understood by scientists), Hardt trawls the sea for all manner of odd reproductive habits, including the deep-sea worm, the Osedax, the males of which are tiny, microscopic animals that live entirely inside the females. From shark virgin births to massive horseshoe crab orgies, the ocean offers a full range of counterexamples to Nemo and Marlin, to say nothing of Adam and Eve.

Despite Hardt’s subtitle, though, much of the book reveals that are connection to the denizens of the deep is far from intimate; it is, in fact, quite tenuous, in the sense that their work is completely alien to us. In part this is because reproducing in the sea requires overcoming incredible logistical problems. How do you find a mate over miles and miles of murky water? Many species have to resort to group sex for the simple reason that it allows for the best chance of any kind of reproduction: species like the Nassau grouper that gather together from far-flung reaches for the purpose of a quick exchange of fluids before dispersing once again. Some females, including lobsters, use urine, relying on the water around them to disperse their pheromones and signal their presence to nearby males.

Evolution has also conferred unexpected advantages on many of the ocean’s denizens, which they exploit on the regular. A good number of female ocean creatures, including sharks, octopuses, and crabs can store sperm for long durations after the initial copulation, an adaptation which has several advantages: the female can dump his sperm in the chance that a better male comes along, can re-impregnate herself again and again from the same male without having to mate again, or simply save it up, waiting for an opportune moment to begin pregnancy (one brownbanded bamboo shark in an aquarium gave birth to a healthy pup some forty-five months after initially copulating).

And then there are the hermaphrodites. For many fish, the males are most virile when they’re young, whereas the females get more fertile as they age—physically larger fish can hold more eggs and produce more offspring. So for many species, including the clownfish, the fish have it both ways: they start off as male, impregnating females left and right; then, as they mature and grow, they switch sex, becoming larger, mature, adult females who can hold more eggs. Known by ichthyologists as BOFFFFs (Big, Old, Fat, Fecund Female Fish), these matriarchs incorporate a number of reproductive advantages not available to those of us stuck with one sex our whole lives.

Hardt’s writing is often spectacular at describing the rituals and courtships of underwater reproduction. Writing of lobster sex, she describes how a female lobster will attract a mate using the scent of its urine and thereafter move into his den. There they’ll spend several days engaged in light foreplay, which she uses to assess if he’s a good match—if he has complete control over his den, for example, and won’t be muscled out by a stronger male. The male will wait until his mate molts, since it provides the most advantageous point to deposit sperm—but it’s also when the female is most vulnerable, lacking even the ability to stand on her own until her new shell hardens. And so the male, immediately after she molts, “stands guard over her soft body, resting on closed claws and may even lightly stroke her with his antennae. At the appointed time, the male circles behind her, attempting a doggy-style mount. But then, in what may be the most tender act of lovemaking in the invertebrate kingdom, he lifts her gently off the seafloor and cradles her in his small walking legs.”

It’s descriptions like these—luxurious and strange—that help drive Hardt’s book. Taken as a whole, though, Sex in the Sea more often gets mired in trivia. Each chapter opens with bullet points of quirky facts and tidbits, adding to a sometimes jocular tone ripe with puns and other silliness (“Groupers like sex on the edge,” “Penis-fencing is serious business—just ask a knocked-up flatworm”). Tonally, it starts to weary after awhile, but perhaps it isn’t in itself always a bad thing, since the work of a book like this is to overload any perception that there’s a right way to do it, and pummeling the reader with facts and minutiae helps accomplish this economically.

Hardt also reminds us how our understanding of sea creatures and their reproductive lives directly affects our own food supply. In both cod and haddock, for example, males and females congregate at different depths, the males swimming in a cluster below the females. Fishing at specific depths, then, either by line or net, will often decimate half of a population, leading to gender imbalances which throw off future reproduction cycles. Other species, including the copepod, that rely on minute temperature gradations for mating rituals and survival, are facing imminent complications from rising sea temperatures. Her point is well taken—after all, who doesn’t want these fish to survive, if only so we can continue to eat them? But it also feels like reaching, since the real point here is to ask not what fish can do for us, but how they have sex. As if we can’t think of these fish, or be interested in their lives, without constantly thinking about what’s in it for us.

The human interest angle runs through the whole book: no matter how varied the sex acts become, there’s an incessant need in Sex in the Sea to find a human analogy for every act. There are microscopic “singles bars” in the sea, male whale songs are likened to the music of Barry White, cuttlefish are described as “cross-dressers,” urine is a “love potion” employed in “golden showers.” This works okay as an introduction into the world of sea sex, but I found myself wanting the book to venture further and further into unrecognizable terrain. Ultimately, when one peers deep into the depths, one sees not humanity’s kinks and recreational activities, but a world that we can barely understand, let alone relate to—a world sovereign and strange, one worth saving not simply because it provides us food. The point should not be to find humanity reflected in every aspect of nature, but rather to reveal how alien our own behavior is to the vast range of life that we share the Earth with. Anything less is just lies for children.