When I was eight years old, my mother

and I helped my aunt move from Franconia, New Hampshire to Omaha, Nebraska, a

journey made west by covered SUV. I had rarely traveled outside my home state

of Idaho, and I watched these new landscapes pass by along car-packed

interstates across Connecticut and New York, through the rolling Amish vales of

Pennsylvania, and into the Midwest’s flat, steady farmscapes. I’d recently read

all of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books, and her

own experience of the American terrain came to mind: “You never know what will

happen next, nor where you’ll be tomorrow, when you are traveling in a covered

wagon.”

This lifelong wanderlust of the Ingalls family defined Wilder’s childhood and formed the basis of the eight Little House novels published between 1932 and 1943, entertaining readers first through the Depression and then into the beginnings of war. The Little House books tell the story of Laura Ingalls, a hardheaded tomboyish character, from toddler to adulthood, beginning, in Little House in the Big Woods, just after her birth in 1867, in a cabin on the Wisconsin-Minnesota border. The books continue west into Kansas’s Indian Territory, where the Ingalls family is lured by government promises of open land, and then back east, where they stop for a time to live in a sod dugout near Walnut Grove, Minnesota, before making a final homesteading journey to De Smet, a small town in the Dakota Territory, the site of Laura’s adolescence and, in 1885, her marriage to Almanzo Wilder, the son of a farmer.

Throughout Wilder’s portrayal, the fictional Ingalls family draws on an abiding reservoir of grit, ingenuity, and American-bred individualism to face down and tame an uncertain world. Wilder’s saga of hard-fought youth in the wilds of frontier America became instantly popular and remains so: Little House in the Big Woods has sold more than 60 million copies, and in 2012 the books were canonized by the Library of America. It can be difficult now, from the remove of adulthood, to determine just what was so appealing about these books at age nine, yet what strikes me still is how much they feel like a manual for attaining a certain kind of life—one you can make with your hands, the hard way.

Wilder wrote the Little House novels late in life, after settling down in Mansfield, Missouri, and writing a column for a regional paper for more than a decade. In 1930, when she was 62, her draft of a 160-page memoir intended for adults, which she titled Pioneer Girl, was roundly rejected by publishers, but it ultimately served as the urtext for the Little House series. In 2014, the South Dakota Historical Society Press published an expansive 472-page hardcover edition of Pioneer Girl, exhaustively annotated by Wilder biographer Pamela Smith Hill. The book became a runaway bestseller and is currently on its eighth printing after selling more than 140,000 copies.

Despite its grandiloquent presentation, Pioneer Girl is really a little book. It covers the same 16-year span depicted in the eight Little House novels, and an awareness of what is left out gives it the air of a preliminary sketch. The annotations fill in missing details about Wilder’s life and, occasionally, delve into rabbit holes of historicity that can make the text a bit overwhelming. (One note provides background on the health benefits of watermelons.) Its publication now and in such expanded form mostly serves to suggest a desire—however lovingly executed—to squeeze out the very last drops of Wilder’s literary legacy.

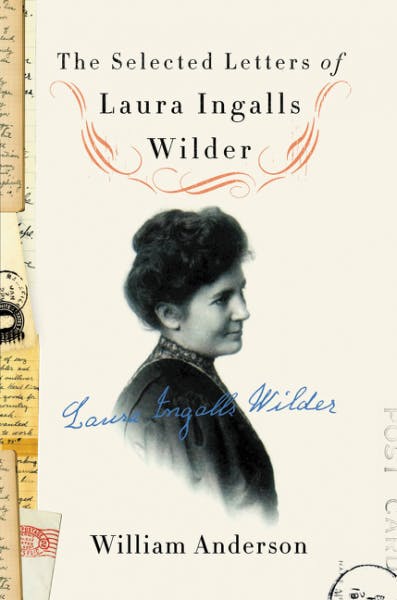

At this point, few drops are left. In addition to Pioneer Girl and the Little House novels, the list of books published by or about Laura Ingalls Wilder includes a diary, a collection of her letters to Almanzo, a collection of her early newspaper pieces and essays, countless biographies, a spun-off series of novels about her daughter’s childhood, and at least two Little House–inspired cookbooks. HarperCollins, whose progenitor, Harper & Brothers, originally published the Little House books, now adds to the pile with The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder—collected and contextualized by William Anderson, another Wilder biographer. This collection, Anderson avers in his introduction, is the last unpublished trove of Wilder’s writing. “There no longer remains a well of her words left to print.” Through all this available matter—and we are now told we have it all—there are many Lauras to know. But who exactly was Laura Ingalls Wilder?

By the time “Mrs. A. J. Wilder,” as she called herself, sat down to handwrite her memoirs at her home in the Ozark mountains, she was far from the world she conjured on the page. “Once upon a time years and years ago,” she began modestly, “Pa stopped the horses and the wagon they were hauling away out on the prairie in Indian Territory.”

Between Wilder’s birth in a “little gray house made of logs” near the Big Woods of Wisconsin, in 1867, and her foray into literature in the 1930s, the frontier had moved on, in that “direction which always brought the happiest changes,” as she wrote in Pioneer Girl. Though Wilder achieved her first newspaper byline in 1894, when the De Smet News and Leader published a letter she’d written about her and Almanzo’s trek to Missouri, she had been beaten to a real literary career by her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, who had become a successful journalist and fiction writer after moving to San Francisco. (Among other assignments, she was Herbert Hoover’s biographer.) Settling in Missouri after three decades of near constant movement, Wilder supplemented the family’s farm income in the 1910s and 1920s by writing for the St. Louis Star Farmer and the Missouri Ruralist, and by serving as secretary-treasurer of the Mansfield Farm Loan Association. As she began Pioneer Girl in 1929 or 1930, Wilder hoped to gain “prestige rather than money” from these stories of her family, which were too good, she thought, to be “altogether lost.”

For a time it seemed that they would be. After Wilder finished the manuscript in 1930, Rose became her mother’s editor and de facto agent. In spite of a persuasive sales pitch, New York literary contacts turned down Pioneer Girl, rejecting both the original version and a draft much shortened by Rose. (The rejection may have been panic-inducing in addition to disappointing for Rose. It is possible, Smith Hill suggests in the introduction to Pioneer Girl, that Wilder was encouraged by her daughter to write her pioneer tales for financial reasons: Rose had spent a then-exorbitant $12,000 building her parents a cozy home in 1928, and after the crash found her bank accounts suddenly depleted.) In a last-ditch attempt, they repackaged the memoir for a third time as what was then referred to as a “juvenile” and sold it to Virginia Kirkus, namesake of Kirkus Reviews, as Little House in the Big Woods.

Even overlooking the shortcomings of the source material, it’s not immediately obvious why the Little House books should have been so wildly successful. While full of adventure, they present fairly simple portraits of human character—Pa is full of heart, Ma of patience, Mary is incessantly good, only Laura struggles with how to be in the world of people—and the books often eschew interior development for simple descriptive action. Set against the wide-eyed, earnest, mischievous, and fictional persona presented in the Little House novels—the Laura that appears in Pioneer Girl is savvy; a child voiced by a woman who has been made aware of adult concerns. Much was lost in the process of abridging to protect younger readers from the harsher reality of Wilder’s lived experience. (In an anecdote left out of the Little House books, a preteen Laura, hired as an overnight nursemaid, awakens to find a whiskey-drunk man looming over her bed, unsuccessfully ordering her to “lie down and be still!”) But there is a great deal missing from here, too, and Pioneer Girl is in many ways more simplistic—its shambling story vastly less troubled by narrative detail and descriptive scene-setting, its writing clearly that of an amateur.

This new collection of Wilder’s letters initially does little to fill in the missing facets of her personality. In early exchanges between the 1890s and 1920, there are simple greetings, letters as short as telegrams, even a few receipts. Often, Anderson’s prefatory material is more illuminating and interesting, and also lengthier, than the letter it introduces. But as the years go by, a few episodes round out some edges. When Wilder travels, her letters reveal a woman enamored with landscape and the essence of the West, hinting at her future career. “The foundation color of the buildings is soft gray,” she wrote to Almanzo from San Francisco in 1915, “and as it rises it is changed to the soft yellows picked out in places by blue and red and green and the eye is carried up and up by the architecture, spires and things, to the beautiful blue sky above.” Later in life, as the Little House series grew in popularity, her letters are devoted to readers—children, parents, schoolteachers, librarians, even a congressman—who flood Wilder with fan mail. The Laura in this period is given to mildly political disquisitions on how things used to be. “The children today have so much that they have lost the power to truly enjoy anything,” Wilder wrote from her ten-room house in 1944. “They are poor little rich children.”

In these correspondences, Wilder dug into the narrative she’d absorbed of her family’s success through determination and entrepreneurial drive. As she repeatedly answered the same questions about the fates of her characters, frequently referring to herself as “Laura,” she consistently upheld her books’ fictions as “truth.” In 1943 she assured a fan that the stories were “literally true, names, dates, places, every anecdote and much of the conversation are historically and accurately true,” but we know this to be false. In letters to Rose from early 1938, as the mother-daughter team conferred about the editing of By the Shores of Silver Lake and the preparation of its sequel, The Long Winter, Wilder discusses the fabrication of the novels’ recurring neighbor character, Mr. Edwards, and explains the creation of her nemesis Nellie Oleson as a composite, modeled after a few different girls from her childhood. But to fans she maintained the fiction: “I heard some years later that she married and went with her husband to Washington state,” Wilder wrote about “Nellie” to a fan in 1943. “There the husband was arrested and sent to the penitentiary for embezzlement, and … Nellie died a few years later.”

Wilder also routinely offered proclamations about the hardships of her upbringing that contrasted with what she saw as the coddling of contemporary youth, writing disparagingly in many of her letters of the “New Dealers” and their dilution of pioneer-hard values. These opinions were often at odds with the role of government in her family’s life: Wilder was secretary-treasurer of the Mansfield Farm Loan association, which made federal loans more accessible for rural farmers, and her father served the nascent prairie authority in various capacities, including as constable and a justice of the peace for De Smet in the 1880s. Wilder papered over these nuances—some of which, such as the federal aid her father requested in the wake of a grasshopper plague, Smith Hill suggests she may not even have been aware of—and continued to insist on the truth of the way of life she was raised in. Perhaps this is just the gentlest of the ravages of age. (Rose, for her part, became a writer of libertarian-edged books and anti-government tracts, which she penned from a late-in-life Connecticut hermitage.) Delivering bittersweet pronouncements about American life as it had been and no longer was, Wilder recognized that the world was passing her by. “I love to go for a drive as well as I ever did,” she wrote to Ursula Nordstrom, her editor, in 1943, but clarified: “We don’t drive horses now. We drive a Chrysler.”

If Wilder was nostalgic for her past, so was the rest of the country. Narratives of self-sufficiency may have been especially appealing to 1930s readers facing a shattered economy, and editors were hungry for stories of the pioneers. After Rose pitched Pioneer Girl, an editor at the Saturday Evening Post beseeched her for other first-person accounts of life in the West to “remind people of ... that spirit.” For the children of this era, perhaps it was comforting to delve into a narrative in which one man, Pa, always knew what to do, and a relative assurance of health, prosperity, and happiness came from merely following the rules he and, to a much-diminished degree, Ma dictated. It was a simple world, a clean slate, a set of forces to be conquered and husbanded.

Whatever the cause, toward the end of Wilder’s life, her correspondences began to hint at the unusual hold her books possessed over young readers. Wilder began receiving piles of letters from schoolchildren—which she answered assiduously, because, she wrote, “I cannot bear to disappoint children.” But as old age crept in, Wilder’s energy, even for young fans, began to fade. Almanzo, ten years her senior, died in 1949 at the age of 92, and only as a widow does Wilder display a truly divergent persona in Selected Letters. “It is very lonely without my husband,” she wrote to a friend from South Dakota, then, “I am very lonely,” and “It is so lonely without Mr. Wilder that at times I can hardly bear it.” Apart from the occasional response to a fan, the once resilient pioneer girl now seemed, more or less, to be waiting to die.

Wilder had begun her novels shortly after her older sister Mary died—her last real connection to those early cabin-bound years—amid economic chaos that threatened to return the country to more primitive times. Initially, she began writing the Little House novels to record a way of life she feared would be lost after her death, a life marked by facing seemingly insurmountable hardships in which the actions of individuals effect the transition to adulthood and the attainment of national prosperity. But she was gradually disillusioned by a country that no longer seemed to value the achievements of her generation in settling and physically building the expanse of the nation.

Perhaps most alluring about Wilder’s novels is that they provide what amounts to a blueprint for attaining the life they describe. The Little House books, particularly the two bearing that title, read as almost biblically detailed how-to guides for creating a prairie fortress against the forces of the world, whether natural, native, or governmental. Among the tasks outlined are point-by-point instructions on smoking meat, churning butter, fashioning bullets, making cheese, preparing a snow-water bath in a cabin in winter, harvesting maple syrup, weaving a straw hat, operating a wheat-thresher, fording a river, washing laundry, constructing a fireplace, digging a well, making a rocking chair, and building a log cabin.

The time of the pioneers is gone, as is Wilder, who died in 1957 at the age of 90. But in her novels—for all the readers who encounter them—she wanted her world to live on. And perhaps that is where the “real” Laura lies, not in the effusion of words by and about her, but in the actions they describe. Neither Wilder’s memoir nor her letters offer up the woman behind them. Instead, she left in her fictions a framework—one made of logs, nails, and the ingenuity for putting them together—for understanding who she was, a pragmatist’s portrait that has become both ephemeral and timeless. As Little House in the Big Woods ends, with the fictional Laura “snug and cozy” in her family’s Wisconsin cabin, the young narrator offers a koan that sums up her creator’s worldview. “This is now,” she thinks. “Now is now. It can never be a long time ago.”