Reading, like religion, can boast of this: If it gets you young

it’s got you good. But both, as you know, have been singed by flashier

pursuits: religion by celebrity, books by screens. “Book culture” indeed sounds

more and more like a contradiction these days, a contradiction that kisses

paradox, since there have never been so many books; in 2013, Forbes

reported that between 600,000 and 1,000,000 books are published each year in

the U.S. alone. The eyes, however, are elsewhere. Our current crop of high

school students has never been without an illuminated gadget in their hands.

Love of literature might be helped if we could choose our parents, or if our

parents had better choices with our teachers.

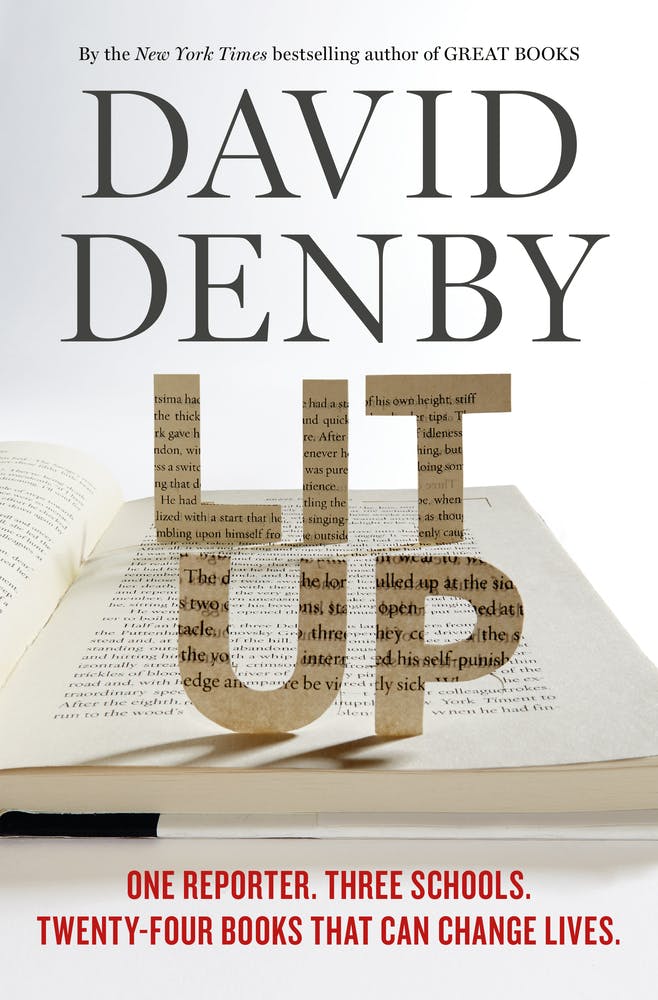

Those of us fortunate to have been snagged early by reading know that teachers are a basal part of maintaining that fortune. High school might be the last chance to turn a low-level reader of pop into a lifelong reader of art: A sophomore in high school is in search of a selfhood; a sophomore in college is in search of a career. In Lit Up, David Denby delivers his bulletin from the messy trenches of high school English classes. He’s been hereabouts before: In 1996 he published Great Books: My Adventures With Homer, Rousseau, Woolf, and Other Indestructible Writers of the Western World, his chronicle of returning to Columbia to gauge how first-year students were faring with the same classics he’d studied there 30 years earlier. Only so-so, it turned out. A vitalizing defense of the canon, with volleys of literary passion directed by a keen critical eye, Great Books appeared when we needed it most, during the nonsensical crescendo of the academic left’s confusion of literature for politics. Since the 1980s, the apostles of Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man, Michel Foucault and their ilk had been busy costuming literature in the Mardi Gras beads and boas of theory. Denby’s return serve was to stress the “body and flavor” involved in the act of reading, its “stresses and pleasures” and “occasional euphoria.”

To point out that the world was an immeasurably different place in 1996 is to emphasize the obvious, but for Denby the fight remains the same: “To argue that reading is good seems as silly as arguing that sex, nature, and music are good. Who could disagree?” Hordes, apparently. Americans disagree every beeping, buzzing, dinging moment of our lives. Gore Vidal said it back in 1965, long before the online coup d’état of our culture: “Americans have never liked reading.” That hurts. Denby’s questions are urgent then: “How do you establish reading pleasure in busy, screen-loving teenagers—and in particular, pleasure in reading serious work? Is it still possible to raise teenagers who can’t live without reading something good?” He doesn’t spend any ink defining “serious” or “good” because he knows there’s no argument there: Time has been mercilessly exact in elevating the serious and good while discarding the frivolous and bad, the merely fashionable. Literature, I’m not sorry to say, isn’t a democracy. Literature is a tyranny—a tyranny of the talented. Here’s the thesis driving Lit Up (please type it out and hand it to your teen):

The liberal arts in general, and especially reading seriously, offer an opening to a wider life, the powers of active citizenship (including the willingness to vote); reading strengthens perception, judgment, and character; it creates understanding of other people and oneself, maybe kindliness and wit, and certainly the ability to endure solitude, both in the common sense of empty-room loneliness and the cosmic sense of empty-universe loneliness. Reading fiction carries you further into imagination and invention than you would be capable of on your own, takes you into other people’s lives, and often, by reflection, deeper into your own.

And here’s the clincher: “If literature matters less to young people than it once did, we are all in trouble.” There’s really no “if” about it, and so yes, we are all in trouble. The question is: How pernicious, how permanent is that trouble? Lit Up is no alarmist screed but a steadfast appeal by a writer who understands that without a devotion to literature, we’re a hamstrung bunch.

Denby sets up watch in tenth-grade classes at three high schools: the Beacon School in Manhattan, a middle-class dream where, according to its web page, students receive “a rigorous well-rounded liberal arts education based on the principle of shared exploration and problem solving”; Mamaroneck High School in Mamaroneck, New York, a Rockwellian suburb in Westchester County, where in 2013 the average property tax was $13,842, the highest in any county in the nation; and James Hillhouse High School in New Haven, Connecticut, where predominantly black students try to learn literature while being brutalized by their socioeconomic realities. Of Denby’s 15 chapters, two are given to Mamaroneck and only one to Hillhouse. It’s Beacon’s book, in other words.

What’s so special about Beacon? His name is Sean Leon, “a dynamo” teacher by way of Ireland and Louisiana, late thirties, highly caffeinated, it seems. He has unwaveringly good taste in writers: Hawthorne and Dostoyevsky, Beckett and Sartre, Faulkner and Plath, Huxley, Orwell, Vonnegut. Often it’s hard to tell if he’s hamming it up for the journalist in the room or if he’s constitutionally given to pronouncements such as: “When I come in, I will never not be here. I will bring it every day. … I’ll stay in this damn building until seven if I have to. I will never fail you.” Leon, says Denby, “had intense spiritual and moral preoccupations,” was “out to save lives,” was “building and saving souls.” So here we have the high-school English teacher as guru and shrink, prelate and christos. How Denby manages to get through this book without once mentioning the film Dead Poets Society is something to ponder, rather like being nabbed by silent cops in Prague without mentioning Kafka.

For his purposes, Denby couldn’t have designed Sean Leon any better. Both subscribe to an essentially Arnoldian ethos. In his 1880 essay “The Study of Poetry,” Matthew Arnold saddled poetry, and by implication all of literature, with some hefty responsibilities:

We should conceive of poetry worthily, and more highly than it has been the custom to conceive of it. We should conceive of it as capable of higher uses, and called to higher destinies, than those which in general men have assigned to it hitherto. More and more mankind will discover that we have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us. Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry.

“The best poetry,” Arnold contends, “will be found to have a power of forming, sustaining, and delighting us, as nothing else can.” There are moments in Arnold’s essay, as there are throughout most of his late-period work, when you almost suspect that his brassy idealism, his vision of literary utopia, must be something of a sham. But no, he means it; the supple gaiety of his style is never not sincere. In the memorable last lines of his essay, Arnold speaks of the “currency and supremacy” that are “insured” to poetry, “not indeed by the world’s deliberate and conscious choice, but by something far deeper—by the instinct of self-preservation in humanity.” That humanity-wide instinct of self-preservation has been a bit rusty these last 100 years, I have to say.

Enamored of Arnold though I am, let me suggest that we pause before assigning literature as a social corrective. Literature is communion, pleasure, and intimations of wisdom, but it doesn’t actually do anything. It can’t delete despair, mend damage, cure dread. It’s pivotal to have the proper words to attach to life’s headlining events, and it’s nice to know you’re not alone, but literature, contra Arnold and Sean Leon, doesn’t save societies or souls. Literature, to summon Wilde’s typically jaunty assertion, is perfectly useless. Or here’s Chekhov’s counsel: “Only what is useless is pleasurable.” Literature’s efficacy remains contingent upon its lack of utility. The minute literature is for something, yoked to an ideology or cause, hijacked for moralizing or indoctrination, is the minute it renounces all claims to autonomy, relevance, and aesthetic potency. That is what Poe meant by “the heresy of the didactic.”

Literature, though, feels useful, and it is, but for you alone. The plea to read is really a plea to selfishness, to your own prudence, since you can’t improve anyone else with your bookishness. (That should be a simple chore, should it not, getting teens to be selfish?) About Leon and his students, Denby writes: “Literature is his obsession, and he wants it to be their obsession.” But obsession, idiosyncratic and bulletproofed against reason, remains stubbornly nontransferable. (Saul Bellow: “Other people’s obsessions don’t turn me on.”) For Leon’s vigor to work, students have to show up already in possession of the impulse for literary love, the urge to an ardent interiority, the requisite ache to comprehend their own confusion, or else no amount of cajoling, however passionate, will succeed. You can’t be coaxed into loving literature any more than you can be coaxed into loving your date from last night, and so literature is for those who are already inclined to need it. It’s a gift from the self to the self—reading done right is a form of romance with the self. In his essay “Eng. Lit. As She Is Taught,” the critic Clifton Fadiman, who taught high school English in the Bronx in the mid-1920s, writes this about literature: “In a very real sense you can’t ‘learn’ it. The teacher who does not cheerfully admit this at once is handicapping both himself and the student.” Fadiman means: Make no promises. Impart your passion, yes. Nudge the nudgeable. But don’t offer anybody redemption with literature.

The supposition, underlying or overt, of any effective high school English teacher is that literature can help kids. Class becomes a rehearsal out loud for what happens inside, suggestions in public for sureness in private. But let’s forget about “identifying with” or “relating to” a book. See yourself too keenly in de Sade or Poe and you’ll soon be seeing yourself in therapy. And with what, I wonder, could you possibly “identify” in The Iliad or The Aeneid? “Educate,” from the Latin educere: “to lead forth.” Literature leads us forth from ourselves, from our own preciously guarded identities. It cares nothing for the validation of identity, only for the upending of it. Great books are not echo chambers for our own personalities. We go to them precisely because in their most sublime moments they bestow on us an alien condition, both lesser and greater than human. We go to them for their aesthetic armature, the stab of their humanity, and the beauty, always the unkillable beauty, of sentences that croon of our rescue from the pat and patently false.

As Denby renders it, each experience at Beacon has the identical structure: At the beginning of a given book students are baffled, a teacher then dazzles them with a grave frisson—“the room was buzzing with excitement”—and then the kids not only abruptly comprehend the book but their lives are abruptly enlarged by it, too. Denby’s exclamations outpace his evidence: “Hawthorne’s defining strength cleared away their adolescent vagueness”; “Mr. Leon woke students up from sloth, and he woke me up from sloth, too”; Leon injected Dostoyevsky’s essence “into their souls”; in a different classroom, “the conversation caught fire” and then “the class was alive” and then “they were close to happiness.” I don’t mean that necessary awakenings didn’t occur in those classrooms, only that Denby’s depiction of them is much too easy, and, it should be said, a bit too bathetic. The chapters end mostly in twitches of maudlin sophistry, with tolls of uplift unearned on the page: By golly they’re getting it, they really are! And some of them surely are, but, as Fadiman remarks in a different essay, “all true education is a delayed-action bomb, assembled in the classroom for explosion at a later date.” If the literary trek from indifference to deliverance were as immediate and efficient as Denby makes it seem, we might no longer have a reading crisis in this country.

Denby’s prose only fitfully breaks from the bad pull of journalese or the Oprahesque jargon of empowerment and self-improvement. I could use up my entire word count here just typing his automatic responses, and I stopped circling them halfway in. His critical skills, too, have atrophied in the 20 years since Great Books. Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot, he thinks, is “a statement of the human condition,” except that the play doesn’t come close to the real condition of most humans. One memoir has “fascinating pages.” About a Vonnegut story: “The students were fascinated.” Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man? “They found him fascinating.” Denby’s cascade of cliché, like all cliché, is telling, and what it tells of is this: his mechanical relation to the task he undertakes. Lit Up has little of the industrious depth and earnest intensity of its predecessor.

At one point, during his class-as-therapy shtick, Leon asks his Beacon students: “Do you feel consumed by anger and hatred?” If they weren’t angry before that leading query they were no doubt angry after it. It’s demonstrative of her dignity that the tenth-grade teacher at Hillhouse, Jessica Zelenski—a single mother with Augean challenges all day long—doesn’t put that question to her students, kids in the crime-ripped warrens of New Haven who should be seething from the multiform injustices of that environment. You get the feeling that Denby wasn’t quite up for the tremendous demands of Hillhouse. Beacon was convenient, after all—Denby lives in Manhattan—and, let’s be honest, Beacon was safer, in more ways than one.

Continuously cheated in their lives, the kids of Hillhouse are cheated anew in Lit Up. Denby’s isolated chapter offers only a glance into their ordeal, and that’s a shame both for them and the book, because the underdog’s story is almost always worthier and more compelling than the champ’s. His brief time at Hillhouse underlines the limits of literature: Those students most in need of great books are by and large too strafed by their environments to invest the necessary force of mind. Sean Leon’s students aren’t lucky because he is an effective teacher—Sean Leon is an effective teacher because his students are lucky. Let’s leave the honorable last word for Hillhouse’s Zelenski: “Maybe they’ll enjoy life more, if I can get them reading. I would like to nurture in them the idea that there are other worlds. You don’t have to experience things the way you do now.”