Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton not only have competing political programs but also, more crucially, rival visions of how to bring about political change. Clinton would no doubt eschew the invidious label of the establishment candidate, but as her own ads and rhetoric show she’s running as the experienced politician who can defend and consolidate the achievements of the Obama years. Sanders, by contrast, presents himself as the candidate not just of change but of a “political revolution.”

While the exact nature of the “revolution” Sanders promises is nebulous, in terms of electoral politics he is making a very clear argument. Relying on traditional constituencies will only doom the Democrats to a perpetual stalemate. To break that logjam, Sanders argues, the Democrats should move to the left on economics, which would bring in a wave of new voters, particularly among the young and low-income. Sanders also believes that such a move to the left would bring back into the Democratic fold demographic groups that have felt alienated by the party, particularly working-class whites, rural voters, and older voters.

“[Y]ou can’t concede the white working-class community, which is hurting,” Sanders told Andrew Prokop of Vox in 2014. “You can’t concede the senior community.” The fact that Sanders is willing to go after such voters makes him an attractive figure. But the danger of his campaign is that these neglected or abandoned voters won’t show up for Democrats on Election Day.

As it turns out, the Iowa caucus will be an excellent testing ground for Sanders’s revolution, because the crucial difference between Sanders and Clinton is his ability to draw in new voters. The polling has been all over the place in Iowa, but according to the respected Des Moines Register poll, the race is very tight, with Clinton enjoying a razor-thin edge over Sanders, 45 percent to 42 percent.

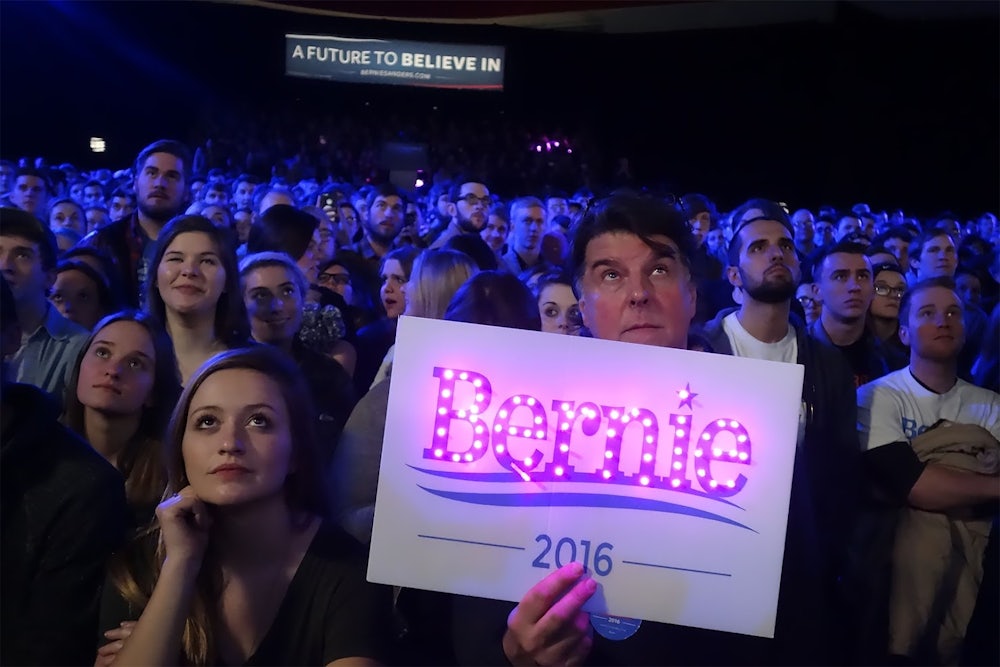

Both the promise and peril of Sanders’s campaign are tied up in the fact that he needs new voters to caucus. “What I sense is that there are a lot of people who participate in the caucus process on Monday night who were previously were not involved in politics—that’s working class people, that’s young people, who now want to direct the future of this country,” Sanders told CNN Sunday morning. “I think, if the turnout is high ... we’ve got a real shot to win this.”

Although Sanders and Clinton are polling very closely, Sanders is winning decisively among the young and the working class. Citing a Quinnipiac poll, The Washington Post notes that “among likely caucus goers under age 45, Sanders held a commanding lead, 78 percent to 21 percent.”

Writing in Jacobin last week, Matt Karp noted a similar demographic skew in favor of Sanders among low-income voters:

In Iowa, a September Quinnipiac poll showed Sanders with a 19-point lead over voters making less than $30,000, while Clinton led voters making over $100,000 by 14 points. This week another Quinnipiac survey gave Sanders a four-point lead overall, while showing income divisions sharpening even further:

Perhaps the most suggestive shard of Iowa data came in a recent Monmouth poll, which shows Clinton far ahead among voters who drive a sedan or SUV, and Sanders holding a solid lead among wagon and truck drivers. (Martin O’Malley, beautifully, did his best among coupe/convertible and motorcycle drivers.)

The risk Sanders faces is that these voters are, by definition, the ones with the least connection to the political system and the ones least likely to show up on Election Day. As Nate Cohn notes in The New York Times, Sanders’s reliance on infrequent voters could be his weak point. “The Des Moines Register/Bloomberg poll found

Mrs. Clinton ahead by nine points among those who said they would ‘definitely’ vote, with Mr. Sanders ahead by ten among those who said

they would ‘probably’ caucus,” Cohn observes.

Iowa is almost a perfect laboratory for testing Sanders’s theory of political revolution. The state is overwhelmingly white and has a large student and rural population. If Sanders can win in Iowa based on a coalition of students and working-class (often rural) whites, then his revolution will have legs. And Hillary Clinton will be forced to come up with a better argument for why she should be the Democratic nominee.