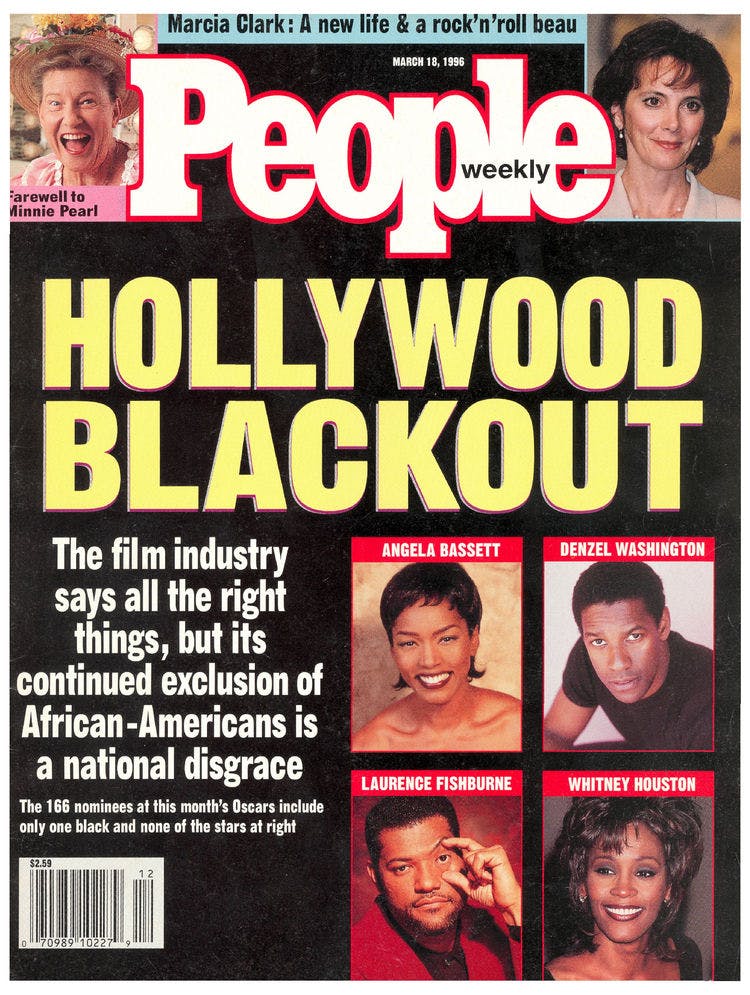

Instead of a glamorous photo of Oscar nominee Mira Sorvino or Kate Winslet, or a puff piece promoting the year’s frontrunners—Braveheart, Apollo 13, Sense and Sensibility—the March 18, 1996 cover of People magazine appeared on newsstands with a damning headline: “HOLLYWOOD BLACKOUT.” The 68th Academy Awards, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg and produced by Quincy Jones, were two weeks away, and the magazine used its audience of nearly 4 million subscribers to announce a shocking discovery: Of the 166 Oscar nominees that year, only one was black.

The count included sound mixers and makeup artists, cinematographers and costume designers; the only African-American nominee in any category was director Dianne Houston, up for Tuesday Morning Ride, a live-action short film. What made the 1996 Oscars noteworthy had little to do with the overwhelming whiteness of its nominees—that was hardly rare. (In the five years that followed, the numbers ranged from zero to four.) Despite the anomalous years of 2002, when Halle Berry and Denzel Washington both won acting awards, and 2014, when 12 Years a Slave won for Best Picture, the Oscars have always been #SoWhite. The 2016 nominations, the second consecutive year with no actors of color nominated and with controversial snubs of Straight Out of Compton and Creed, aren’t an aberration.

But the awards season of 1996 was one of the few times that

whiteness made national headlines. There

were calls for a boycott, questions about whether a black Oscars host and

producer should step down, and disavowals of racism by white Academy members. Jesse

Jackson’s Rainbow-PUSH Coalition announced an Oscars protest,

telling reporters: “It doesn’t stand to reason that if you are forced to

the back of the bus, you will go to the bus company’s annual picnic and act

like you’re happy.”

Landon Jones, then-editor of People magazine, was in attendance at the 1995 Academy Awards when he noticed something strange. “First of all, the audience was entirely white,” he told me. “Then I realized that the seat-fillers were entirely white.” The seat-filler positions—beautifully-dressed extras who swoop in when audience members leave their seats so that TV viewers don’t notice empty chairs—often went to the friends and family of Academy members. None were black. Neither were any of the people who went onstage to accept an award that night. “I came back to People and said, ‘We need to do a story about this,’” Jones continued. The following February, after the nominations were announced, a team of People reporters called every nominee to ask a single question: Are you black?

“We know Meryl Streep is white,” Jones said, but in a pre-IMDB age the only way to find out the race of lower-profile nominees was to work the phones. “The reporters hated it when I said they had to ask all these nominees if they were black,” Jones said. The results of that survey were accompanied by a 3000-word cover story alleging that “exclusion of minorities has become a way of life in Hollywood,” describing the effects of institutional racism within the movie industry, from the Academy to studio boardrooms and union rosters.

People found that in 1996, only 2.3 percent of the Director’s Guild and 2.6 percent of the Writer’s Guild membership were African-American. The numbers in the union of set decorators was even smaller. “What’s wrong is considerably more significant than whether Whitney Houston…gets another conversation piece for the powder room,” People’s Pam Lambert wrote. “Hollywood’s creations are the mirror in which Americans see themselves—and the current racially skewed reflection is dangerously distorted.”

The issue sold poorly on newsstands—institutional racism can be less glamorous than the latest celebrity divorce—but it received widespread media coverage. When Jones went on CNN’s Reliable Sources to promote the story, the panelists were amazed that People had produced such a substantive piece of journalism. One guest described is as “the sort of thing we might have expected from the New Republic or New Yorker.” Another asked why those magazines hadn’t done a story like this themselves. Howard Kurtz, the host, had a theory: “One of the reasons you don’t see this in magazines like The Atlantic or the New Republic is that some of those magazines have almost no black staffers themselves. They might be reluctant to make an issue of this.”

The Academy’s leadership quickly went on the defensive. “Show

me the wonderful performances that have been overlooked,” responded Bruce Davis, the

Academy’s executive director. That was easy—easier than it is today. As public discussion of racism has

moved mainstream over the past 20 years, overly-cautious studios have retreated further from offering

films that represent black life. 1995 featured Denzel

Washington and Don Cheadle in Devil in a Blue Dress (Cheadle had

already won Best Supporting Actor from the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association), Laurence Fishburne in Othello, Morgan Freeman in Seven, and Angela Bassett in Waiting to Exhale, which had a score composed by Babyface.

As Jesse Jackson met with studio executives and called press conferences, the industry fired back. “The Academy is probably the most liberal organization in the country this side of the NAACP,” Davis told the Los Angeles Times. Peter Bart, editorial director of Variety, published a snarky letter, informing Jackson that “protests and picketing are passé” and that “Johnnie Cochran and his client, O.J. Simpson, have sharply reduced the number of good souls around who will go out on a limb to extend a helping hand.”

The presence of Quincy Jones and Whoopi Goldberg at that year’s ceremony gave people an easy way to argue that Hollywood didn’t have a race problem—and even if it did, this was the wrong time to speak out. Jones had asked Oprah Winfrey to greet celebrities on the red carpet, and she told reporters she was “furious” at Jackson, promising this would be “the most multi-ethnic Oscars show anybody’s ever seen.” Recounting the incident to Playboy a year later, Goldberg said she was ready to “rip [Jackson] a new behind.”

He basically put me and Quincy in the position of choosing to do this thing we wanted to do and felt was a very positive thing to do, or to stand up alongside him. He put us in the position of looking like we were kissing somebody’s ass.

For his part, Quincy Jones was careful to publicly emphasize that he agreed with Jackson’s cause, if not his target. The two spoke before the ceremony and Jackson agreed not to picket outside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the ceremony was being held. Instead, Jackson asked church leaders to encourage their congregations to protest outside local affiliates of ABC, which would be airing the ceremony. “We are going to open up the consciousness of America,” Jackson announced, and he suggested Oscar attendees wear rainbow-colored ribbons as a statement of solidarity.

The morning after the Academy Awards, the protest was deemed a “non-event,” a “box-office flop,” and an “epic tactical goof.” Around 75 protesters had joined Jackson outside L.A.’s ABC affiliate, 300 gathered in Chicago, and a dozen people showed up in Washington. The only person at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion that night wearing a rainbow ribbon was Quincy Jones; none of the other black presenters, including Denzel Washington, Sidney Poitier, and Will Smith, had worn one. (“Hey, Jesse’s gonna have to give a brotha some warning next time he wants to throw a boycott. I had my tux ready,” Smith joked to a reporter the following year.)

Jackson’s protest was mocked on Saturday Night Live, and during the ceremony itself the cause was reduced to a punchline. “I just saw Ross Perot outside yelling and screaming,” Nathan Lane said onstage while presenting an award. “He wants to know why more nutty billionaires weren’t nominated.”

And then there was Whoopi Goldberg’s opening monologue, where she ripped into Jackson with a barely-veiled hostility:

Look, I want to say something to all the people who sent me ribbons to wear, you don’t ask a black woman to buy an expensive dress and cover it with ribbons. … Enough with the ribbons, done. Jesse Jackson asked me to wear a ribbon, I got it. I had something I wanted to say to Jesse right here, but he’s not watching so why bother?

A year later, the Los Angeles Times looked back at Jackson’s protest to see what progress had been made. Jackson,

who had developed a reputation as the “Energizer bunny” of activism, had

returned his focus to other issues, such as the 1996 presidential campaign. Minority activists

within the industry were disappointed that further meetings hadn’t

materialized. Despite the 1997 nominations of Cuba Gooding Jr. and Marianne Jean-Baptiste, the Los Angeles Times drew

a depressing conclusion about the lack of diversity within the industry: “What

a non-difference a little more than a year makes.”

After two decades, the story is much the same. The most recent study of the Academy’s membership found that 94 percent of voting members were white and only 2 percent were black. (Studio executives are 94 percent white.) Minorities continue to be disproportionately under-represented onscreen, behind the scenes, and in the director’s chair, and the only prominent African-American nominees at this year’s Academy Awards will be the Weeknd and his two collaborators, nominated for Best Song, from Fifty Shades of Grey.

But the swift response to #OscarsSoWhite by the Academy—which last week announced immediate reforms to its membership rules, pledging to remove voting rights from retired members while actively recruiting minority applicants—would have been unimaginable 20 years ago. Variety—the industry magazine that in 1996 confidently reassured readers that “Hollywood hires on merit” and “the Academy is hardly a bastion of racist sentiment”—published a cover story this week declaring “Shame On Us.” No one has suggested that the involvement in this year’s ceremony of a black host (Chris Rock) and a black producer (Reginald Hudlin) is an adequate rebuttal to charges of racism.

Some of this may be lip service, and no one should declare victory any time soon, but with social media, single activists like Jesse Jackson are no longer needed to swoop in to generate media coverage—a Twitter hashtag can generate the same momentum. The most important difference between the “Hollywood Blackout” of 1996 and today may be what happens next.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Steve McQueen won an Academy Award for Best Director in 2014. The Oscar that year went to Alfonso Cuaron.