“Stefan Zweig,” Volker Weidermann’s Ostend begins, “is sitting in a loggia on the fourth floor of a

white house that faces onto the broad boulevard of Ostend.” The year is 1936,

and the setting is a familiar one. The book’s opening pages are an

evocation-by-numbers of the epoch loved, lost, and longed for by his

protagonists: Austro-Hungarian elegists and expatriates Stefan Zweig and Joseph

Roth. In self-imposed exile before the start of World War II, seeking refuge in the

kind of geographically liminal resort town that only seems to exist in Zweig

and Roth stories (this one is in northern Belgium, but could be anywhere in Old

Europe), the writer-rivals drink, take lovers, and reminisce about the empire

that was, while steeling themselves against the Reich that is to come.

Here, on Ostend’s “extravagantly wide boulevard” with its “great casino…ice creams, parasols, lethargy, with wooden booths,” each

decorative modifier reminds us that the world of Weidermann’s text is the world

of the beautiful, the useless and the vanished, the world that Zweig, in his

“last innocence…believed to be eternal.” We hardly need to know much about the

specifics of Ostend to recognize it and Weidermann keeps the atmosphere

dreamily vague. In this telling, Ostend is like Wes Anderson’s Zubrowska in The Grand Budapest Hotel—his movie was, after

all, an homage to Zweigian nostalgia—nothing but a collection of idylls and

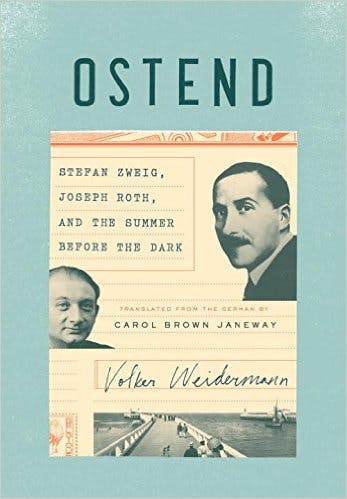

images taken from the post-Hapsburg playbook. Weidermann’s language (the book

was written in German and is translated by Carol Brown Janeway) is at once

haunting and ornamental: an antique music-box of melancholic atmosphere.

But Ostend, in its strongest moments, is less a recap of Central European midcentury nostalgia than a reflection on what that nostalgia really means. Weidermann traces the complexities of the relationship between Zweig—the urbane, successful, “Western Jew” from Vienna—and his quasi-protegé Roth, the misanthropic “Eastern Jew” from unheralded provinces, who sought refuge in the capital. Weidermann offers us insight into what, exactly, was so powerful about the myth of that vanished empire and the myths we all tell ourselves about who we are.

Drawing on the two men’s letters, along with quotes from their friends and lovers, Weidermann creates a world that blends fiction and biography. What paradise are these two men—different in every way, and yet united by their shared alienation—hoping to regain? It is the figure of Roth—brilliant, furious, and inevitably thwarted—that emerges as the more compelling of the two. The vanished Austro-Hungarian Empire that the cosmopolitan Zweig takes for granted, rural transplant Roth clings to with dogged necessity:

old Austria and its monarchy, its empire, that took him, the fatherless Jew who grew up so far from the great glittering capital, and raised him up, and opened the world to him. A state that was a universe, that encompassed many different peoples without distinguishing between them, and in which one could travel freely without a passport or papers of any kind.

The extravagant loggias, the magnificent boulevards, the parasols are, for Roth, not just aesthetic or even nostalgic signifiers; they’re symbols of liberation. The world of yesterday—to use the title of Zweig’s elegiac autobiography—is the world that even Roth feels he can enter. Zweig is less clearly drawn, as is his relationship with the old Vienna. We know he is as nostalgic for it as Roth is—but why?

Weidermann

hints that Zweig is less nostalgic for something

than he is a nostalgist by temperament: in love with vanished things precisely

because they have vanished. After all, Weidermann notes, early Zweig was a

historian: a chronicler not of the fin de

siècle Vienna he later becomes virtually synonymous with, but of the

foibles of eighteenth- and seventeenth-century monarchs in his various early

biographies. “If it was the world of Mary Queen of Scots, Marie Antoinette, or

Joseph Fouché,” Weidermann writes, “he knew every historical and political

detail…None of it had anything to do with the world he actually lived in.” It

is only in distance that Zweig finds grace.

And war creates the greatest distance of all. It is the first World War, of which Zweig is at the outset only hazily conscious, that cleaves the Vienna-that-was from the Vienna-that-is; so too is it the moment that creates that Vienna: freezes it, like one of Zweig’s tableaux of Marie Antoinette, as art. Artistic unity comes only through recollection from the other side of chaos. As Zweig puts it in one of the letters Weidermann quotes:

Everything was smashed in the course of those days. Eternally, irreparably. And yet it was an extraordinary moment. ‘As never before, thousands upon hundreds of thousands felt what it would have been far better they had felt in peacetime, that they were as one.’

Yet, all too often, Ostend feels like the story of those “hundreds of thousands”—a study in collective Zweigian nostalgia—rather than the story of Zweig and Roth: two individual human beings. Weidermann’s odd decision to blend biography with novelistic episodes works on an atmospheric level, but it’s less convincing on a narrative level. Characters and episodes are painted with such impressionistic strokes; virtually devoid of dialogue, Ostend prefers to have its characters speak through real-life letters, reflecting on the incidents Weidermann has just imagined. It’s a curious kind of double-treatment, and one which only heightens the sense of nostalgia, of imagined tellings and retellings, that permeates Ostend.

But it also keeps us at a distance. Weidermann writes, for example, that Roth and Zweig’s friendship “was an aerial battle being fought in dire straits by the two writers. Aerial chess between friends. Who would give way? Could Zweig save his friend? Did he even want to? The man who wanted to free himself of all shackles was now attached to this particular shackle and couldn’t get free.” Roth’s alcoholism, and his increasing bitterness towards Zweig, lead him ultimately to loneliness.

As a biographer, Weidermann speaks with authority: his assertion comes supported by the letters and quotes interwoven with the text. But as a storyteller, he gives us little to go on. Even Ostend’s scenes of writers meeting and drinking at Ostend’s Café Flore contain virtually no dialogue, no chance for us to see either Zweig or Roth as fully present within the text. They exist less as characters than as the vague subjects of remembered anecdotes.

Weidermann is at his best both as a biographer and a storyteller when he allows himself moments of concreteness that blast through Ostend’s dreamlike atmosphere. The detail that, for example, a young Joseph Roth liked to “reinforce his statement with an emphatic ‘that’s a fact’” does more to render his rougher edges than pages of meditations on his relationship with Zweig. Or for instance, when Zweig attempts a white lie—he claims he cannot visit Roth because there are no appropriate flights—and Roth responds by suggesting travel arrangements, these moments encapsulate their relationship better than conjecture, however lyrical, ever could. Moments of tiny truth like these only heighten the sense that the nebulous world of Ostend, divorced from place, from time, and from human nature itself, is a fiction within a fiction.

It’s no surprise that the most emotionally powerful moments in Ostend come not from Weidermann’s narrative of Zweig and Roth but his analysis of their respective works. Towards the end of their respective lives, after their tense, alcohol-soaked parting in Ostend, Roth writes the novel Confession of a Murderer about a bastard son, aching for his father’s love, searching for temporary acceptance through hedonism; Zweig writes Beware of Pity, of how a soldier’s guilt leads him into a toxic relationship of mutual dependence. Zweig and Roth, unreconciled before the latter’s early death from drink, attain closure only in their words.

Ostend is

engaging as a meditation on the act of creation, one that explores how we make

refuges out of our own pasts. In a 1941 letter to a friend, Zweig marvels at

how he feels little connection to the once-Austro-Hungarian town of Brody—Roth’s

hometown—newly invaded by the Germans. “We lack any connection…Brody does not

signify to me what Insterburg does…there is only one supreme connection:

language is our only home.”