Last week, Donald Trump was once again disgusted. Commenting on Hillary Clinton’s awkward bathroom break during the last Democratic debate, he said, “I know where she went, it’s disgusting, I don’t want to talk about it. No, it’s too disgusting. Don’t say it, it’s disgusting, let’s not talk.”

It’s not the first time that Trump has been perturbed by a bodily function. As Frank Bruni noted in his New York Times column, Trump has been publicly disgusted by Marco Rubio’s sweat and by the idea of pumping breast milk. Then there was his notorious comment about Fox News host Megyn Kelly, in which he conveyed an almost visceral revulsion: “You could see there was blood coming out of her eyes, blood coming out of her wherever.”

The Trump campaign has stunned bemused pundits by growing in strength with every controversy and outrageous policy proposal, like banning foreign Muslims from entering the United States. It has finally forced them to admit that his success comes not despite these things, but because of them.

What if disgust is a distinct part of that?

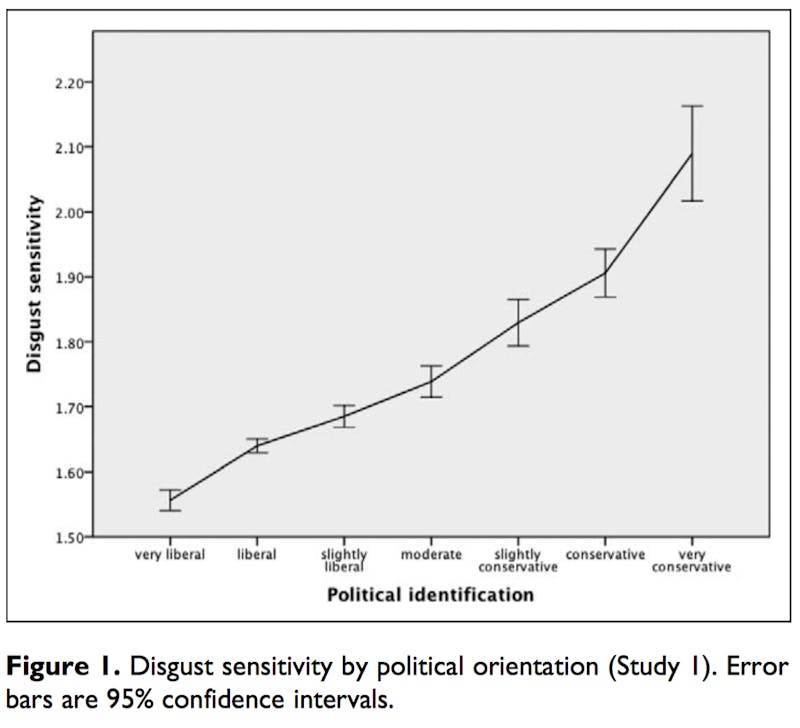

In 2012, a team of academics from Europe and the U.S.—Yoel Inbar, David Pizarro, Ravi Iyer, and Jonathan Haidt—published a paper titled “Disgust Sensitivity, Political Conservatism, and Voting,” looking at the role disgust plays in political orientation. The researchers posited three different types of disgust: interpersonal disgust (i.e., the feeling produced by drinking from the same cup as someone else); core disgust (the response to maggots, vomit, dirty toilets, etc.); and animal-reminder disgust (how we react to corpses, blood, anything that evokes our animal nature).

Disgust, they write, “serves to discourage us from ingesting noxious or dangerous substances,” but also plays a role in moral and social judgments. Those who feel more disgusted by unpleasant images, smells, or tastes judge more harshly that which violates their subjective moral code.

The team had respondents position themselves on a political scale from conservative to liberal. The respondents then stated how strongly they agreed or disagreed with statements like “I never let any part of my body touch the toilet seat in a public washroom,” and rated other hypotheticals according to the level of disgust they generated. Even when controlling for age, education, geography, and religious belief, individuals with higher “disgust sensitivity” were found to be more likely to tolerate wealth inequality, view homosexuality negatively, and place more belief in authoritarian leaders and systems.

Most strikingly, interpersonal disgust was an important predictor of anti-immigrant attitudes.

Trump, of course, is a well-known, admitted germaphobe. “One of the curses of American society is the simple act of shaking hands,” he wrote in The Art of the Deal. “I happen to be a clean hands freak. I feel much better after I thoroughly wash my hands, which I do as much as possible.”

Trump even described shaking hands as “barbaric” in an interview with Dateline in 1999, saying, “They have medical reports all the time. Shaking hands, you catch colds, you catch the flu, you catch it, you catch all sorts of things. Who knows what you don’t catch?”

Beyond the aversion to hand-shaking, Trump used to pre-test his dates for AIDS, and reportedly avoids pushing elevator buttons.

The connection between modern xenophobia, disgust sensitivity, and the strength of Trump’s campaign is fairly easy to make. As Inbar, Pizarro, Iyer, and Haidt point out, “Disgust evolved not just to protect individuals form oral contamination by potential foods, but also from the possibility of contamination by contact with unfamiliar individuals or groups.” And after all, Trump’s success has come not from presenting voters with detailed policy proposals, but from connecting with them on a gut level.

If liberals find themselves immune to such appeals, it may be because liberals and conservatives have different physiological reactions to disgusting images and situations. Last year, researchers at Virginia Tech observed liberal and conservative brains under fMRI machines, and found that, “Remarkably, brain responses to a single disgusting stimulus were sufficient to make accurate predictions about an individual subject’s political ideology.” Furthermore, they showed that our emotional responses are tightly intertwined with our belief systems.

In a TED Talk, Haidt proposed that liberals tend to heavily skew their moral matrix towards protecting people from harm and promoting fairness, while conservatives construct theirs from a five-pillar approach that includes authority, in-group loyalty, and purity—in other words, ideas of what is and is not disgusting. What Trump cleverly does is incite disgust-based reactions as a way to then speak to these other elements of his followers’ moral universe. His standard stump speech, borrowing from both billionaire former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and France’s Marine Le Pen, offers a clear window into this approach.

“It’s coming from more than Mexico,” he has said. “It’s coming from all over South and Latin America, and it’s coming probably—probably—from the Middle East. … The U.S. has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems.” The response to disgust is recoil, which in many ways is the opposite of curiosity. Disgust doesn’t generate a desire to better understand a complex issue, but rather a wish for a simple explanation and an impulse to shut out what is so disgusting. By presenting America’s problems as the spread of an infectious disease, Trump immediately generates the disgust response.

The disgust response feeds into an “in-group” response: What is disgusting is exterior, and the group must be protected from it, which in turn provides comfort and reinforces a shared sense of identity. “People are pouring across the southern border,” Trump says. “I will build a wall. It will be a great wall. People will not come in unless they come in legally. Drugs will not pour through that wall.” During the last Republican debate, he literally labeled the Iran nuclear deal as “horrible, disgusting, absolutely incompetent.”

David Pizarro, a professor of psychology at Cornell who studies disgust, says that while it is only one component of a political ideology, he was surprised at the robustness of the connection between holding conservative views and being easily disgusted. “Trump,” he adds, “is using a strategy that I would predict would be very effective” in connecting with certain voters in a deep way. Pizarro points out that disgust is an easier emotion to elicit than anger, happiness, or sadness, and that disgust is furthermore characterized by its exclusionary and associative characteristics.

When Trump invokes “rapists, drug dealers, killers,” or talks about Marco Rubio’s sweating, or says that Hillary Clinton got “schlonged,” it presents his supporters, caught in the intersection of disgust and fear, with people against whom they can recoil. Feminism, Islam, a majority-minority society, pressing 1 for English and 2 for Spanish, Barack Obama himself—there is something bad, something impure that has infiltrated America, and it must be expelled.

This leads to a desire for a strong, authoritarian leader to deal decisively with the problem—and that leader, for them, is Trump. Indeed, his sexist comments reinforce the unease some men feel with politically and economically powerful women, fueling their desire for a man to reassert control.

Interviewed by CNN on their response to his proposed ban on Muslim travel to the United States, Trump supporters seem eager to flaunt this disgust. “I don’t want them here, who knows what they are going to bring into this country,” one says. “Bombs, ISIS, I don’t know, they need to go.”

When reporters bring up the proposal to bomb the homes of terrorists, the reaction is even clearer. “Absolutely,” a woman says with a clear look of, well, disgust on her face. “People will continue to reproduce and they will raise their children in their beliefs.”

None of this is based in a reasoned

analysis of what effective policy means. It is the primal reaction of voters to

what frightens and disturbs them.

When it comes to Mexicans, Muslims, and women, Trump and his supporters might be literally disgusted. “So long as he does it right,” says Pizarro, “he is tagging that emotion to other people.” The risk for Trump is that emotions go both ways. By voicing so much disgust, he might very well find that, to other voters, he has become an object of disgust himself.