At Texas State University, I teach an honors course called “Demonology, Possession, and Exorcism.” It’s not a gut course. My students produce research papers on topics that range from the role of sleep paralysis in reports of demonic attacks to contemporary murder cases in which defendants have claimed supernatural forces compelled them to commit crimes.

In fact, talk of demons isn’t unusual in Texas. The first day of class, when we watched a clip of an alleged exorcism at an Austin Starbucks, many of my students said that they’d seen similar scenes in the towns where they’d grown up.

A few students even admitted their parents were nervous that they’d signed up for the class. Maybe these parents worried their kids would become possessed, or that studying possession in the classroom might make demons seem less plausible. (Perhaps it was a mix of both.)

Either way, these parents aren’t a superstitious minority: a poll conducted in 2012 found that 57 percent of Americans believe in demonic possession. Nonetheless, demons (invisible, malevolent spirits) and exorcism (the techniques used to cast these spirits out of people, objects or places) are often thought of as relics of the past, beliefs and practices that are incompatible with modernity. It’s an assumption based in a sociological theory that dates back to the 19th century called the secularization narrative. Scholars such as Max Weber predicted that over time, science would inevitably supersede belief in “mysterious forces.”

But while the influence of institutionalized churches has waned, few sociologists today would claim that science is eliminating belief in the supernatural. In fact, in the 40 years since the blockbuster film The Exorcist premiered, belief in the demonic remains as popular as ever, with many churches scrambling to adapt.

Exorcism’s golden age

So why has exorcism made a comeback? It may be that belief in the demonic is cyclical.

Historian of religion David Frankfurter notes that conspiracy theories involving evil entities like demons and witches tend to flare up when local religious communities are confronted with outside forces such as globalization and modernity.

Attributing misfortune and social change to hidden evil forces, Frankfurter suggests, is a natural human reaction; the demonic provides a context that can make sense of unfamiliar or complex problems.

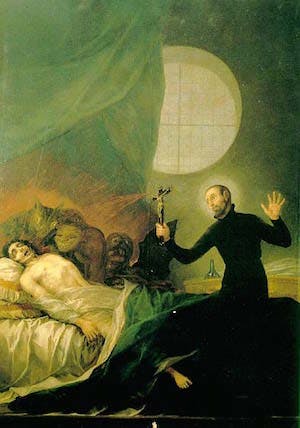

While Europeans practiced exorcism during the Middle Ages, the “golden age” of demonic paranoia took place in the early modern period. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands were killed in witch hunts and there were spectacular cases of possession, including entire convents of nuns.

The Protestant Reformation was a key contributor to these events. The resulting wars of religion devastated Europe’s population, creating a sense of apocalyptic anxiety. At the same time, exorcism became a way for the Catholic Church, and even some Protestant denominations, to demonstrate that their clergy wielded supernatural power over demons – something that their rivals lacked. In some cases, possessed people would even testify that rival churches were aligned with Satan.

But by the 19th century, medical experts such as Jean-Martin Charcot and his student Sigmund Freud had popularized the idea that the symptoms of demonic possession were actually caused by hysteria and neurosis. Exorcists came to be seen as unsophisticated people who lacked the education to understand mental illness – a view that made exorcism a liability for churches instead of an asset. This was especially true for American Catholics, who had long been disparaged by the Protestant majority as superstitious immigrants.

The Exorcist effect

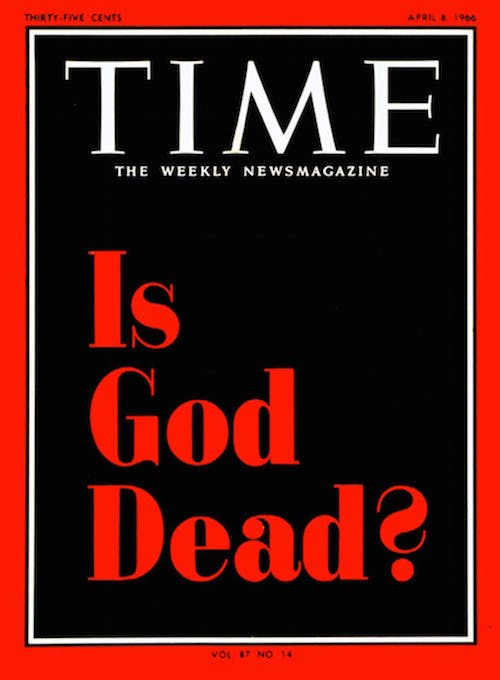

By the time William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist was published in 1971, the secularization narrative had gone mainstream. In 1966, Time magazine had run its famous cover asking “Is God Dead?” In 1970, Gallup found that 75 percent of Americans claimed religion was losing influence – the highest percentage in the history of the poll, which was first conducted in 1957.

Blatty’s protagonist, Damien Karras, is a Jesuit psychiatrist-priest who has lost his faith. At the end of novel, Karras lies dying from his battle with the demon Pazuzu. He cannot speak, but his eyes are “filled with elation”—presumably because he now has positive proof that demons and, by extension, God, actually exist. Through the character of Father Karras, Blatty captured a widespread feeling of longing for the supernatural in a disenchanted age.

While the Jesuit-run magazine America panned The Exorcist as “sordid and sensationalistic,” Blatty proved that Americans were not dismissive of the idea of exorcism. In 1971 and 1972, the novel spent 55 weeks on The New York Times bestseller lists. The film adaptation grossed over US$66 million in its first year. In 1990, as part of homily given in New York City’s St Patrick’s Cathedral, Cardinal John O’Connor even read from The Exorcist

in order “to dramatize the reality of demonic power.”

A demonic renaissance

Today a significant segment of the population reports belief in demons.

According to a 2007 Baylor Religion Survey, 48 percent of Americans agreed or strongly agreed in the possibility of demonic possession. And in a Pew Research Survey conducted that same year, 68 percent of Americans said they believe in the presence of angels and demons.

While the surveys can’t reveal what exactly people mean when they say they “believe in demons,” it’s clear that these people don’t constitute a superstitious minority. Rather, they’re a normal part of today’s religious landscape.

People have historically used evil spirits to explain any number of misfortunes, whether its a physical illness or routine bad luck. But today, demons are frequently used to interpret contemporary political issues, such as abortion and gay rights. Since the 1970s, Protestant deliverance ministries have offered to “cure” gay teenagers by casting out demons. This practice now has corollaries in Islam—and even in Chinese holistic healing methods. When the state of Illinois legalized gay marriage in 2013, Bishop Thomas Paprocki held a public exorcism in protest. Politically, the bishop’s ritual served to frame changing social mores as a manifestation of demonic evil.

Similarly, Catholic exorcists in Mexico held a magno exorcisto in May 2015 aimed at purging the entire nation of demons. The mass exorcism was partly motivated by the drug wars that have devastated the country since 2006. But it was also in response to the legalization of abortion in Mexico City in 2007.

During one Mexican exorcism, a demon (speaking through a possessed person) confessed that Mexico had once been a haven for demons. According to the four demons identified in the exorcism, hundreds of years ago, Aztecs had offered them human sacrifices; now, with the legalization of abortion, the sacrifices had resumed.

Divided over demons

In the Baylor Religion Survey, 53 percent of Catholics said they either agree or strongly agree in the possibility of demonic possession. Twenty-six percent disagreed or strongly disagreed, and the rest were undecided. Progressive Catholics still regard exorcism as an embarrassment, and there are also increasingly vocal atheists and skeptics eager to cite the practice of exorcism as an example of the absurdity of religion. But in countries like Italy and the Philippines, there is active demand for more Catholic exorcists.

Church authorities are keenly aware that if they do not provide the spiritual services these people need, Pentecostal deliverance ministries will. In the past, the Church had much more ability to tailor its message to its audience. But in an age of Twitter and cellphone cameras, an exorcism performed in one country will be witnessed by the entire world.

Pope Francis seems especially skillful at navigating the question of demons. While he has inspired progressive Catholics with his stances on climate change and social justice, he has also emphasized the reality of the devil. In 2014, the Congregation of Clergy formally recognized the International Association of Exorcists. This is a group of conservative priests that has existed outside the Curia since 1990, and has lobbied for recognizing and normalizing the practice of exorcism. Founding IAE member Gabriele Amorth has even attributed the group’s sudden success to Pope Francis.

Perhaps the greatest example of Francis’s demonological savvy occurred on May 13 2013, when he placed his hands on a young man in a wheelchair after celebrating mass in St Peter’s Square. (This young man was, in fact, the same Mexican parishioner believed to be possessed by four demons.) Video shows the boy heaving and slumping forward under Francis’s unusually long embrace.

To those who feel the Catholic Church ought to take exorcism seriously, this was a clear example of Francis performing a public exorcism. But to those who regard exorcism as a relic of the Dark Ages, Church authorities can plausibly claim that this was only a blessing, perhaps lasting just a little longer, due to the pontiff’s sincere compassion for the young man.

For a church with over a billion followers, it’s a tough—but necessary—balancing act.

![]() This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.