Not all that long ago, voters and pundits alike pondered why civil rights protesters with Black Lives Matter and other organizations were choosing to only interrupt campaign events starring Democratic presidential candidates, and not Republicans. They were asked, why challenge Bernie Sanders, Martin O’Malley, and Hillary Clinton when they’re on your side? But now that Donald Trump, the Republican frontrunner, has seen multiple interruptions of his rallies, we have two answers to those queries.

One, it’s plain that being vocal at a Democratic rally didn’t carry with it the same risks of physical assault and racial insult as one tends to encounter when confronting Trump. But protesting a Democratic candidate has also become less urgent than it was in the days before Sanders began saying Sandra Bland’s name, O’Malley was considering a comprehensive racial justice platform, and Clinton had ever mentioned structural racism (or her husband’s role in strengthening it). It’s become clear that the three candidates have all but calcified their sales pitch on racial justice, confident that what they saying now will be all they’ll need to say to win the support of black voters.

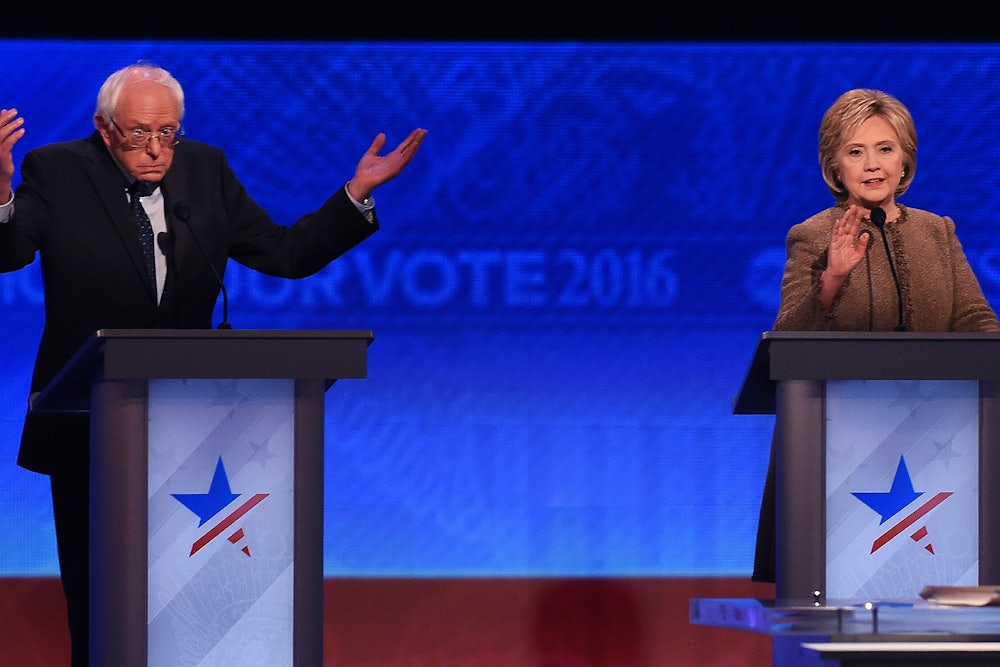

You can see this process happening over the course of the three Democratic primary debates, the most recent of which took place Saturday night in New Hampshire, the first since the city of Chicago released the Laquan McDonald execution video. I wanted to pick apart what each said about McDonald being shot 16 times by a cop, and to examine the candidates’ debate over their racial justice reform ideas. But McDonald’s name never came up Saturday night, and that debate has not occurred.

In the first Democratic debate, we heard the first of the stump speeches masked as dialogue. Some policies, such as following the recommendations of President Obama’s policing commission, get the backing of some or all of the candidates. Sanders’s language has centered largely on prison sentencing reform, spotlighting marijuana legalization and accountability for police violence. On Saturday, he added some community-policing boilerplate: “We need to make police departments look like the communities they serve in terms of diversity.” The also-ran, O’Malley, who was the first Democratic candidate to propose a plan for racial justice reform, has stuck largely to his credentials as the former governor of Maryland, hyping his record of crime and incarceration reduction—all while steadily ignoring the biggest blight on his civil rights ledger, the “zero tolerance” policing he employed as a crime reduction tactic while mayor of Baltimore.

Clinton’s rhetoric, while still a miniature speech in the form of an answer, has at least offered more variety during the three debates. She used the first debate to offer bullet points of a racial justice platform she wouldn’t begin detailing for another two weeks. The second debate offered a chance for her to offer a strong comment on the student protests at the University of Missouri and Yale. On Saturday night, though, she reverted to what sounded like prepared remarks. “We have systemic racism and injustice and inequities in our country,” she said, “and in particular, in our justice system that must be addressed and must be ended.”

If Clinton had said those very words on the stump in June, without having been pushed to do so by black liberation activists, it would likely have inspired if not a swell of black support, then a rise in black engagement with her ideas. Today, it won’t even make a headline.

Ironically, this is a testament to the success of the Black Lives Matter movement and associated organizations; they have so ingrained racial justice as a presidential platform issue that the issue has joined other presidential topics as fodder for the pundit class, platforms are distilled into easily digestible soundbites. And the more they’re repeated, the more we assimilate them into our understanding of the candidate. Once outside the assumed priorities of the Democratic presidential hopefuls, structural racism is now just political boilerplate for the left.

Our retail politics prize simple declaration over meticulous detail, but to be fair, one can hardly blame the candidates for having a script ready for race questions. In each of the three debates, race has come up just once. Either it’s been one query, or one quick series of them—and generally, those questions have been terrible.

CNN’s moderators for the first Democratic debate didn’t even bother to ask the question themselves, instead soliciting an asinine question from a viewer—“Do black lives matter, or do all lives matter?”—that could only prompt one answer, plus talking points. But the second and third debates have been even worse in this regard. Both moderators proclaimed that It’s Time To Talk About Race by asking the candidates about something called the “Ferguson Effect,” a disproven theory that seeks to explain police laziness or intentional slowdowns by blaming criticism of said police and calls for reform. Yet that rubbish formed the basis of both introductory race questions from both the CBS and ABC moderators. Hence, anchors from two major media organizations were unable to spark meaningful debate among three presidential hopefuls about one of the foremost news issues of this moment.

That said, it is telling that O’Malley in the second debate and all three candidates on Saturday night chose to completely ignore the “Ferguson Effect” question posed to them. As the New Republic’s Steven Cohen noted, it shouldn’t have been difficult at all for Clinton, Sanders, or O’Malley to stare at the moderator and say something such as, “The ‘Ferguson Effect’ is nonsense. Structural racism is real. Can you ask me about something real, please?” But the Democratic candidates didn’t do that. They opted instead for the talking points.

That should tell us a lot. Racial justice made it onto their platforms, and that is a victory. But if the moderators can’t ask better questions, and the candidates can’t deviate from what they’ve memorized, we aren’t watching a debate. We’re watching them try to ace an oral exam they think they’ve been assigned by Black Lives Matter. And as long as the candidates simply say the things black folks want to hear rather than debate the issues, they will leave the stage thinking that they’ve passed with flying colors.