If you want to be a great writer, should you withhold your sentimental tendencies? The answer for most critics and writers seems to be yes. Sentimentality is often seen as a useful way of distinguishing between serious literature and the not-so-serious, probably best-selling kind. “Sentimentality,” James Baldwin wrote, is “the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion…the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel.” While sentimentality is false, grandiose, manipulative, and over-boiled, high literature is subtle, nuanced, cool, and true. As Roland Barthes, the dean of high cultural criticism, once remarked: “It is no longer the sexual which is indecent, it is the sentimental.” This sentiment (yes sentiment) has been around since at least the early twentieth century and is still a subject of debate in the review pages of numerous media outlets today. But is it true? Whether you are for subtlety or against sentimentality, is this a good way to think about writing your next novel?

We decided to test this theory by using new techniques in sentiment analysis drawn from the field of computer science. While not uncontroversial, sentiment analysis is a widely used technique to understand people’s beliefs or feelings about the world around them. It has been applied to the study of movie reviews, audiobooks, political elections, and more recently the relationships between fictional characters in Shakespeare’s plays. Essentially sentiment analysis uses fixed lexicons that map words to either positive or negative sentiments and then scores a piece of text accordingly. The longer the text the better it works. It thus seemed like a natural tool for capturing the feelings of characters in novels, which give us a great deal of text to work with.

We looked at a collection of roughly 2,000 novels published over the past half century which were labeled according to a variety of categories—bestsellers, prizewinners, books reviewed in the New York Times, most widely held books in libraries, as well as some popular genre categories like Romance, SciFi, Young Adult Fiction, and Mysteries. We then searched for indications of differing levels of sentimentality using dictionaries developed by Bing Liu, one of the more prominent researchers in the field. The more a novel contained strongly positive or negative words (abominable, inept, obscene, shady, on the one hand, admirable, courageous, masterful, rapturous on the other), the higher its score. However complex literary sentimentality may be, the assumption is that in order to be sentimental at a minimum you need a sentimental vocabulary.

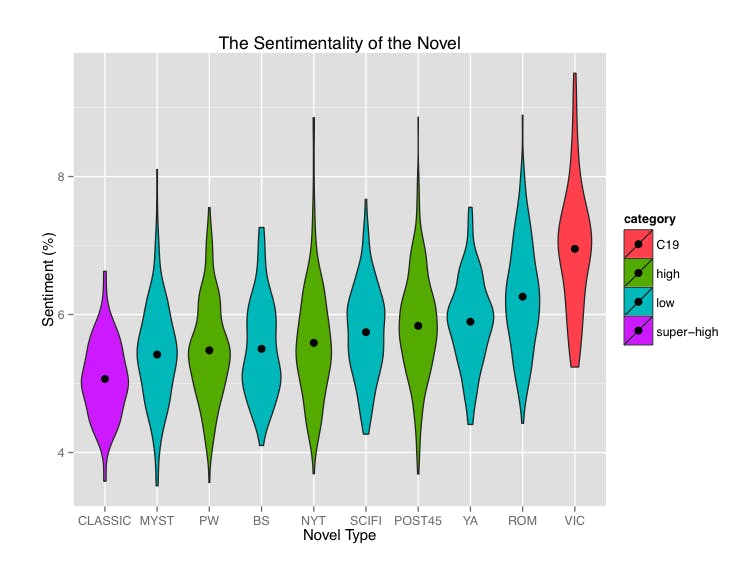

Below you see a comparison of the varying levels of sentimental vocabulary in each of our 10 categories. The most telling aspect of the graph is the way the novels of the nineteenth century (labeled “VIC”) represent an altogether different world in terms of sentimentality. These are the novels of Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, Anthony Trollope, Emily Bronte, and their contemporaries. To give you an idea of what this difference is like, the average amount of sentiment vocabulary in the nineteenth-century novels accounts for just under 7% of all words in a given novel. For prizewinning fiction from the past decade, by contrast, that number is about 5.5%. This means that for a given novel of 100,000 words (about the length of Pride and Prejudice), a reader will encounter on average 1,500 more sentimental words, or about seven and half more per page. That’s an enormous difference from a reader’s perspective. In this sense, one could see our current antipathy to sentimentality as a longstanding reaction to a distinct moment in the novel’s history when emotion reigned.

The other noticeable feature about

this graph is the way it is not well-sorted according to our distinctions

between “high” and “low” categories (“popular” and “serious” might be another

way to label them). Some popular genres like Romance, Young Adult Fiction (YA),

and Science Fiction (the latter being surprising to us) do use sentimentality

to a higher degree than so-called highbrow novels reviewed in the New York Times (NYT) or those that win

literary prizes (PW). (Here the difference is significant though less extreme –

Romances for example use about 0.75% more sentimental words than prizewinners,

or roughly 3-4 more per page.) On the other hand, the most widely held novels

in libraries since 1945 (POST45) use levels of sentiment on par with more

popular categories like SciFi and YA fiction, just as our high-brow categories

like New York Times novels and Prizewinning novels show no difference with more

popular groups like the Bestsellers or the Mysteries.

In other words, up to a certain point, sentimentality does not help us distinguish between ostensibly high-cultural things and low-cultural things (or popular things and serious things). It neither qualifies nor disqualifies you from a variety of possible outcomes, such as being reviewed in a major newspaper, selling books, or even winning prizes. Indeed, when we looked more closely at the sales data of the novels reviewed in the New York Times we found no correlation between sentiment and sales. It doesn’t appear to be a factor in helping or hurting a book’s sales.

What sentimentality does do, however, is strike you from the list of twentieth century classics (CLASSIC). While the list of the 400 most-widely held novels in libraries since 1945 do not exhibit significantly lower levels of sentimentality (indeed it appears to be the opposite), the more constrained list of the 60 or so most canonical novels published between 1945 and 2000 (an admittedly very subjective list) appear to show more restraint when it comes to using a sentimental vocabulary. These are works by authors like Toni Morrison, Susan Sontag, Don DeLillo, Kurt Vonnegut, Joan Didion, Ralph Ellison, among many others you’ve definitely heard of. (For those who are interested, Burroughs, Nabokov, and Bellow are at the top of that list while Cheever, Didion and Gordimer are at the bottom).

How strong is this effect? It works out to three or four fewer sentimental words per page, which is about the difference between Prizewinning novels and Romances. In other words, the difference in sentimentality between the super-canon and today’s high-brow novels is roughly the same as the difference in sentimentality between high-brow novels and Romances. And again this is not an insignificant difference. There appears to be some kind of selection mechanism at work that winnows the field at least partially according to a bias towards less sentimentally inflected literary works. Sentiment may not be the driving factor, but it is a noticeable outcome.

Interestingly, a good deal of this effect can be accounted for by the under-use of positive vocabulary. If we look at the differences between negative and positive words, we see how a significant amount of the literary canon’s under-average performance is accounted for by a disproportionate absence of positive words (about 60% of the canon’s under-usage of sentiment is accounted for by a decrease in positive words even though they account for less than half of all available words). There appears to be an assumption at work among the canon that reality is harsh and positivity distorts the truth. As Zoe Heller once commented, the sentimental “prettifies” reality.

And yet when we measured sentimentality in a different way—this time as the expression of emotions (i.e., the literal use of words like love, happiness, joy, sorrow, anger, etc)—we found that this distinction between the super-canon and the other major categories actually disappeared. There was no longer any significant difference between the groups (with the exception again of Romances, YA, and of course the nineteenth-century novels). It’s not that emotions are absent from the most serious of serious literature. Rather, what is missing is a kind of explicit articulation of belief, what we might call, for lack of a better word, “conviction.” Over time we seem to institutionally value novels that downplay the clarity of their own beliefs. This makes a good deal of sense—novels that endure do so because they represent more open belief systems, ones that allow readers across broader stretches of time to engage with them and explore their own beliefs. As Leslie Jamison says, “Behind every sentimental narrative there’s the possibility of another one—more richly realized, more faithful to the fine grain and contradictions of human experience.”

Sentiment analysis is by no means a

perfect science. These are admittedly blunt tools to understand the

complexities of literary sentimentality. But they can give us a more general

idea of the degree of sentiment within novels across broad stretches of time

and different types of writing. Sentiment analysis is a useful lens through

which to understand the broader intensities of characters’ beliefs within

novels.

At stake in all this, however, is something more fundamental. At stake is the development of tools and techniques that can be used to confirm or refute our own widely held beliefs about cultural practices, especially when those beliefs are circulated by people who wield a great degree of cultural authority, i.e. critics and established writers. Even though these beliefs are based on little more than hunches, they often carry very strong normative claims (if you want to be a serious novelist, don’t be sentimental…). If you look closely at the anti-sentimental language, you see a lot of moralizing going on, which can itself be highly sentimental. One finds appeals to the “cardinal sin” or “taboo” of sentimentality, or as we saw above the “faithfulness” of the unsentimental point of view. As numerous people have pointed out, discussions about literature often assume this kind of religious tone, with a host of commandments in tow (this is right, this is wrong). This is where sentiment—the sentiment of those in charge—masquerades as truth.

Computation, on the other hand, can help us ground our beliefs about cultural practices using more evidence. In this particular case, the story turns out to be more complicated, and certainly less binary, than the literary establishment would have us believe. Ironically, the story that a computer tells about sentimentality is far more nuanced than the bundle of impressions and intuitions we often use to form our opinions about literary qualities.

Our advice to writers? Based on the available evidence, if you want to write one of the fifty most important novels in the next half-century, then by all means avoid sentimental language. But if you want to get published, sell books, be reviewed, win a prize or simply make someone happy, then emote away and just write a good novel.