Almonds: crunchy, delicious, and…the center of a nefarious plot to suck California dry? They certainly have used up a lot of ink lately—partly inspired by Mother Jones’s reporting over the past year. California’s drought-stricken Central Valley churns out 80 percent of the globe’s almonds, and since each nut takes a gallon of water to produce, they account for close to 10 percent of the state’s annual agricultural water use—or more than what the entire population of Los Angeles and San Francisco use in a year.

As Grist’s Nathanael Johnson put it, almonds have become a scapegoat of sorts—“the poster-nut for human wastefulness in California’s drought.” Or, as Alissa Walker put it in Gizmodo, “You know, ALMONDS, THE DEVIL’S NUT.” It’s not surprising that the almond backlash has inspired a backlash of its own. California agriculture is vast and complex, and its water woes can’t hang entirely on any one commodity, not even one as charismatic as the devil’s nut almond.

And as many have pointed out, almonds have a lot going for them—they’re nutritious, they taste good, and they’re hugely profitable for California. In 2014, almonds brought in a whopping $11 billion to the state’s economy. Plus, other foods—namely, animal products—use a whole lot more water per ounce than almonds.

So almonds must be worth all the water they require, right? Not so fast. Before you jump to any conclusions, consider the following five facts:

1. Most of our almonds end up overseas. Almonds are the second-thirstiest crop in California—behind alfalfa, a superfood of sorts for cows that sucks up 15 percent of the state’s irrigation water. Gizmodo’s Walker—along with many others—wants to shift the focus from almonds to the ubiquitous feed crop, wondering, “Why are we using more and more of our water to grow hay?” Especially since alfalfa is a relatively low-value crop—about a quarter of the per acre value of almonds—and about a fifth of it is exported.

It should be noted, though, that we export far more almonds than alfalfa: About two-thirds of California’s almond and pistachio crops are sent overseas—a de facto export of California’s overtapped water resources.

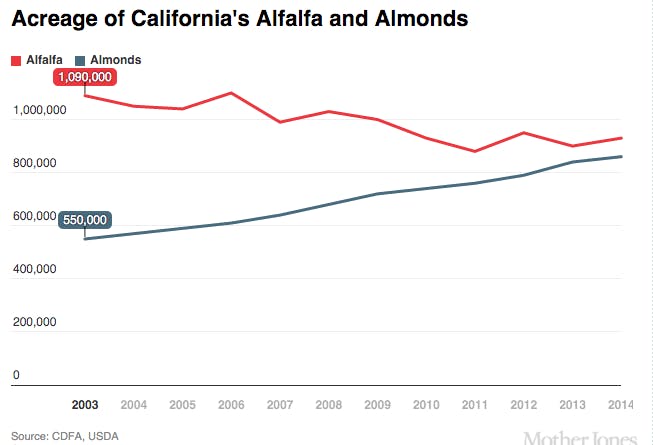

2. While alfalfa fields are shrinking, almond fields are expanding—in a big way. The drought is already pushing California farmers out of high-water, low-value crops like alfalfa and cotton, and into almonds and two other pricey nuts, pistachios and walnuts. This year, California acreage devoted to alfalfa is expected to shrink 11 percent, and cotton acres look set to dwindle to their lowest level since the 1920s.

Meanwhile, the market is pushing almonds and other nuts in the opposite direction. At a confab in California’s nut-rich, water-challenged San Joaquin County, Stewart Resnick, chief of Paramount Farms, by far the state’s largest nut grower, explained why in a speech, as documented by an account in the trade journal Western Farm Press. Almonds, he said, deliver farmers an average net return of $1,431 per acre. Pistachios, another fast-expanding nut hotly promoted by the Paramount farming empire, net even more: $3,519 per acre.

Given that Paramount reportedly manages 50,000 acres of combined almonds and pistachios, it’s safe to say there’s big profits in growing those nuts. And the company, which also buys and processes nuts from other farmers and sells them under the Wonderful brand, plans to expand by 50 percent in the next five years. Currently the company farms 30,000 acres on its own and buys pistachios from farms occupying another 100,000 acres. By 2020, the company’s “goal is 150,000 partner acres, 33,000 Paramount acres,” which would be a 40 percent jump in just five years. And that’s on top of the 118 percent expansion in pistachio acres over the past decade, according to figures Resnick delivered at the conference.

3. Unlike other crops, almonds always require a lot of water—even during drought. Annual crops like cotton, alfalfa, and veggies are flexible—farmers can fallow them in dry years. That’s not so for nuts, which need to be watered every year, drought or no, or the trees die, wiping out farmers’ investments.

Already, strains are showing. Back in 2013, a team led by US Geological Survey hydrologist Michelle Sneed discovered that a 1,200-square-mile swath of the southern Central Valley—a landmass more than twice the size of Los Angeles—had been sinking by as much as 11 inches per year, because the water table had fallen from excessive pumping. In an interview last year, Sneed told me the ongoing exodus from annual crops and pasture to nuts likely played a big role.

4. Some nut growers are advocating against water regulation—during the worst drought in California’s history. “I’ve been smiling all the way to the bank,” one pistachio grower told the audience at the Paramount event, according to the Western Farm Press account. As for water, that’s apparently a political problem, not an ecological one, for Paramount. “Pistachios are valued at $40,000 an acre,” Bill Phillimore, executive vice president of Paramount Farming, reportedly told the crowd. “How much are you spending in the political arena to preserve that asset?” Apparently, he meant: protect it from pesky regulators questioning your water use. He “urged growers to contribute three-quarters of a cent on every pound of pistachios sold to a water advocacy effort,” Western Farm Press reported.

5. Mostly, it’s not small-scale farmers that are getting rich off the almond boom. With their surging overseas sales, almonds and pistachios have drawn in massive financial players hungry for a piece of the action. As Mother Jones reported last year, Hancock Agricultural Investment Group, an investment owned by the Canadian insurance and financial services giant Manulife Financial, owns at least 24,000 acres of almonds, pistachios, and walnuts, making it California’s second-largest nut grower. TIAA-CREF, a large retirement and investment fund that owns 37,000 acres of California farmland, and boasts that it’s one of the globe’s top five almond producers.

Then there’s Terrapin Fabbri Management, a private equity firm that “manages more than $100 million of farm assets on behalf of institutional investors and high net worth clients” and says it’s “focused on capitalizing on the increasing global demand for California’s agricultural output.” In a piece earlier this year, The Economist pointed out that Terrapin had “bought a dairy company and some vineyards and tomato fields in California, and converted all to grow almonds, whose price has soared as the Chinese have gone nuts for them.” The magazine added that “such conversions require up-front capital”—e.g., to drop wells—”and the ability to survive without returns for years.” Those aren’t privileges many small-scale farmers enjoy.

This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of our Climate Desk collaboration.