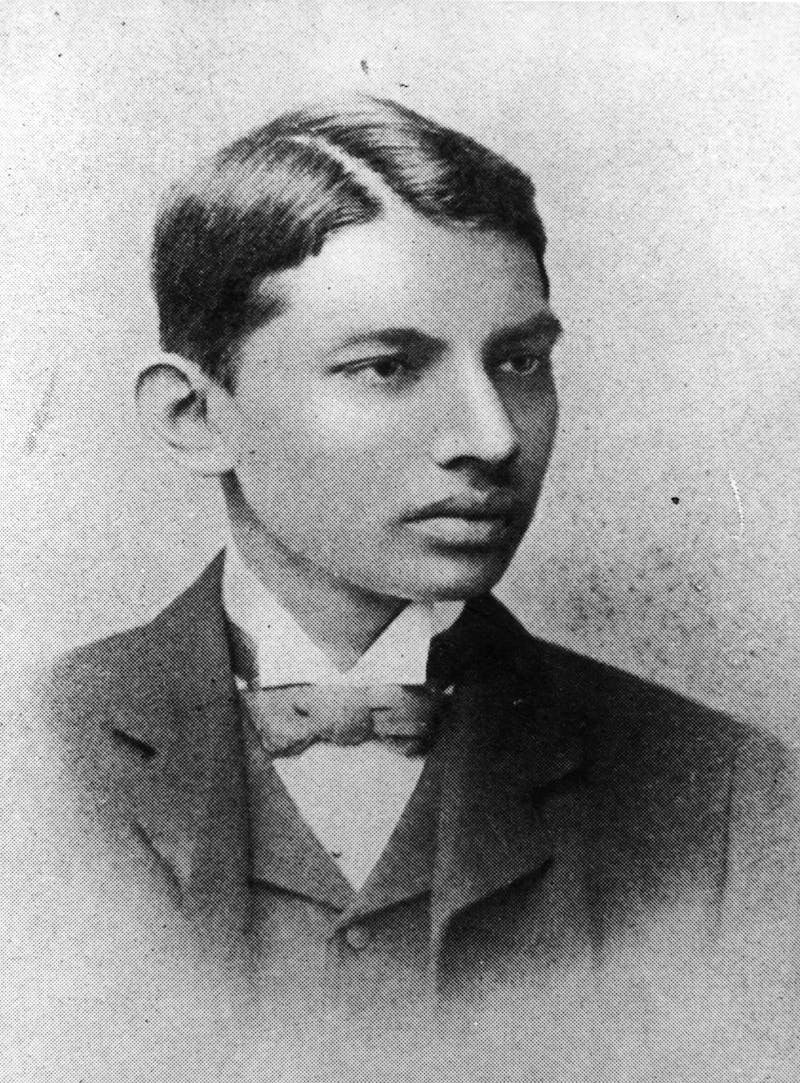

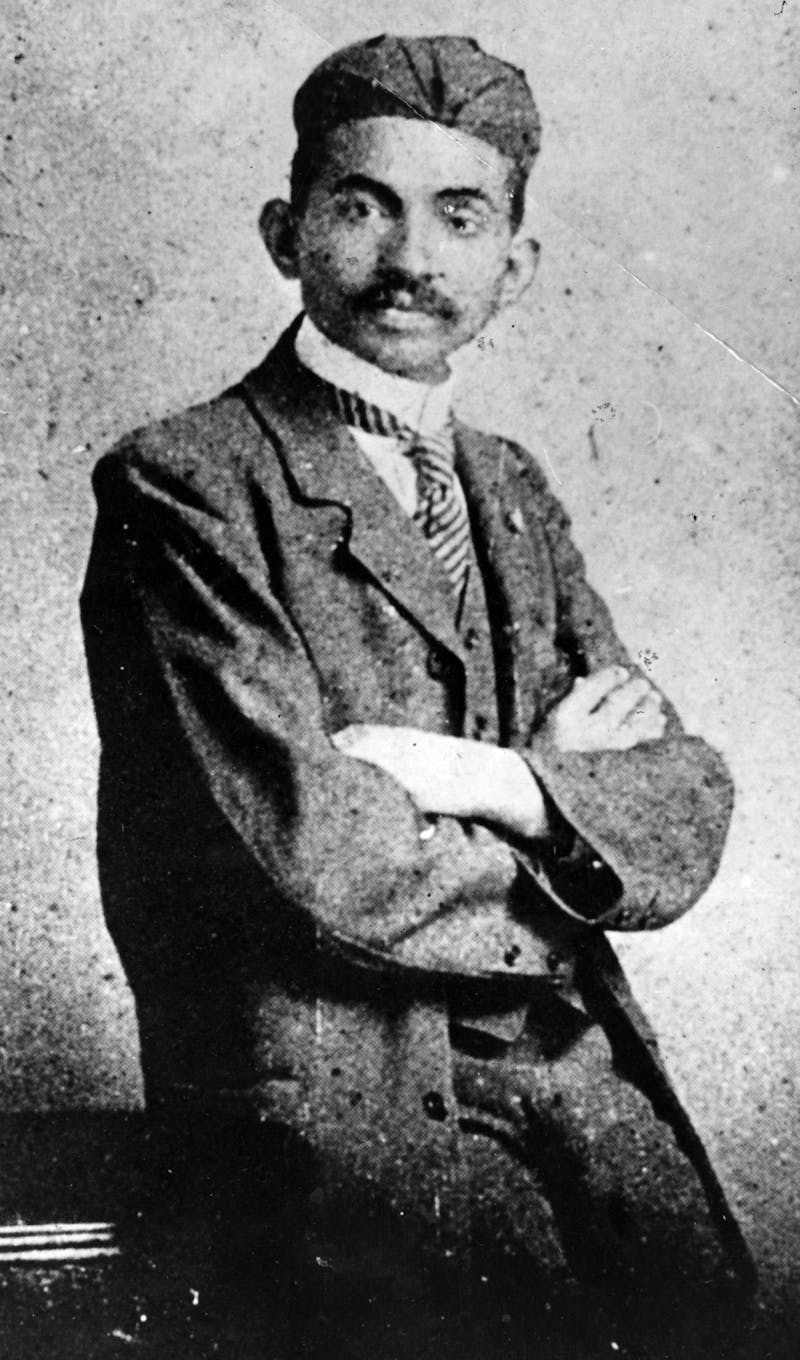

Gandhi was 24 years old when he arrived in Natal, South Africa in May 1893, the month in which white settlers celebrated the 50th anniversary of Natal’s annexation by the British Crown. Gandhi was called to the Bar in June 1891 and was struggling to establish a law practice in Bombay when the firm of Dada Abdulla & Co., offered him a year-long contract to assist in a legal matter on the southern tip of Africa. Gandhi took up the offer consisting of a first class passage to Natal, living expenses and a fee of £105. When Gandhi landed at Port Natal there were roughly as many Indians as whites in the colony. Natal’s population was pegged at 584,326 in 1893. Whites numbered 45,707 (8 percent) and Indians 35,411 (6 percent). Zulus made up almost 85 percent of the population.

Central to the imperial project in this part of the British Empire was the subjugation of the Zulu. The Zulu kingdom rose to power during the reign of Shaka (1816–28) and his brother Dingane (1828–40), consolidated under their brother Mpande (1840–72), and collapsed during the reign of Mpande’s son, Cetshwayo (1872–84). The British contrived ways to separate Europeans from Africans. Administratively, they divided the colony of Natal from Mpande’s Zulu kingdom along the Thukela River in 1843 while tracts of land were granted to amakhosi (chiefs) in Natal who lived relatively autonomous lives in these reserves. The aim of this “ethnic transfer” was to separate white from black in order to achieve settler hegemony.

The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in the late 1870s required a stable environment for white economic exploitation. British officials felt that some Zulu chiefs were becoming too independent and Sir Bartle Frere, British High Commissioner for South Africa from March 1877 onwards, set out to annex the Zulu kingdom. He found a pretext to declare war in 1879. The Zulus won the Battle of Isandlwana against the then greatest military power in the world but eventually succumbed. Cetshwayo was exiled to the Cape but Queen Victoria subsequently gave him permission to rule a portion of his former kingdom in the hope that he would restore order. Cetshwayo’s son Dinuzulu was proclaimed king when Cetshwayo died in 1884 but this position was largely ceremonial. With the power of the Zulu kingdom eroded, the pace of land dispossession by both British and Boer accelerated.

This is the canvas against which the arrival of Indians in Natal from 1860 must be viewed. The Indian population included indentured workers, “passenger” migrants who arrived at their own expense, and “time-expired” Indians who had completed their contracts of indenture and made Natal “home.” Larger wholesale traders like Dada Abdulla, who brought Gandhi to Natal, and smaller dukawallahs and hawkers, many of whom had just completed their indentures, were spread out across the city and countryside of Natal. A steady trickle of Indians followed the discovery of diamonds to Kimberley in the 1870s and then in the 1880s the gold rush into the Transvaal.

This dispersal of Indians across the colony, their trespassing into white trading and residential monopolies, and their ability to undercut prices and offer credit to white and black customers alike, raised the ire of many settlers. Harry Escombe, future Prime Minister of Natal, told the Wragg Commission of 1885–87 which had been established to investigate alleged abuses in the system of indenture, that the presence of Indian traders “entailed a competition which was simply impossible as far as Europeans were concerned, on account of the different habits of life.”

Gandhi felt the weight of white power virtually upon his arrival in the colony. Within days of landing in Natal, the magistrate asked Gandhi to remove his turban when he went to court with Dada Abdulla. Gandhi refused and stormed out of the courtroom. Barely two weeks later, Gandhi was thrown off a first-class train compartment at Pietermaritzburg on the night of June 7, 1893 when a white passenger protested against sharing the carriage with a “coolie.”

Gandhi returned to India in July 1896 to publicize the Indian plight in Natal and to bring back his family. At a speech in Bombay, Gandhi stated that whites in Natal desired to “degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

This was a theme that would run through much of Gandhi’s life in South Africa. India occupied a privileged position in the hierarchy of British imperial possessions. There was a feeling among some British colonial officials that Indians were positioned higher up the chain of civilization than Africans as they originated from the same Aryan root. The managers of the Empire’s jewel were keen to avoid events in other parts of the British globe offending or, worse, inflaming, national feeling on the subcontinent. In geopolitical terms, Indians in South Africa counted far more than the Zulu, a sense that Gandhi was keen to tap into.

Gandhi was also partial to the idea of Indo-Aryan bloodlines. The Black African stood outside and below these civilized standards. This echoed a broader global context in which race had become a dominant theme in Western intellectual life in the nineteenth century, emphasizing a scientific understanding of race that focused on biological differences. European industrial progress and the conquest of black peoples were seen as the empirical evidence of racial science which offered Europeans a clear validation of their superior place in the world. Many works of the time believed Africans were less aesthetically appealing than Europeans, even ugly, barbaric and less intelligent.

The Gandhian vision sought to embrace diasporic Indians and claim affinity with Europeans as (civilized) Aryans and imperial citizens. This vision was conspicuous in its exclusion of Africans. Gandhi’s newspaper Indian Opinion, for example, had little to say about Africans. “Gandhi had neighbors like John Dube with whom he wanted little to do,” writes Isabel Hofmeyr, in her book Gandhi’s Printing Press. While Phoenix, where Gandhi opened a settlement in 1904, was in close proximity to Dube’s Ohlange Institute, “the leaders of these two remarkable communities kept their distance and met rarely. ... Both expounded different versions of ‘race pride’ with Dube involved in redeeming ‘Africa’ and Gandhi in nurturing ‘India.’”

During his years in South Africa, Gandhi sought to ingratiate himself with Empire and its mission. In doing so, he not only rendered African exploitation and oppression invisible, but was, on occasion, a willing part of their subjugation and racist stereotyping. This is not the Gandhi spoken of in hagiographic speeches by politicians more than a century later. This is a different man picking his way through the dross of his time; not just any time, but the height of colonialism; not through any country, but a land that was witness to three centuries of unremitting conquest, brutality and racial bloodletting.

Over the decades the complexities, ironies and blemishes of Gandhi’s South African years have been smothered to serve the political expediencies of the day. Commemorating Gandhi is part of a vigorous debate in post-apartheid South Africa about “history and heritage, ‘truth’ and ‘lies,’ and memory and make-believe.” The cultural historian Annie Coombes asks us to consider seriously how best to represent national history through cultural institutions and monuments because elites tend to invent stories and historical figures which are seen as the glue to reconcile competing interests in transforming societies. While Coombes calls for an understanding of South Africa’s past that goes beyond a simple binary between apartheid and resistance, Gandhi has been reinvented as an icon of non-racialism and as one of the foremost fighters against segregation.

While a corpus of critical work on Gandhi has emerged over the years, individually, these works have done little to dent the overwhelming storyline of his heroism—of an individual who slowly but inexorably transformed into a Mahatma by the time he left the shores of South Africa in 1914.

Excerpts from The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer Of Empire, by Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed. ©2016 Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed. Published by Navayana Publishing Pvt Ltd. and in the USA by Stanford University Press in hardcover, paperback and digital formats, sup.org.