I never saw my great-grandmother cook with written recipes. She was born in 1909 and was 70 years old by the time I came along; it’s likely that she’d committed to memory her entire culinary repertoire—all Southern cuisine she’d learned to prepare growing up in French Camp, Mississippi—by then. She rarely flubbed a dish, at least during the 25 years I saw her cooking for our family, neighbors, and friends before she passed away.

Plenty of my African American friends marvel over their family elders’ ability to cook from memory, processes so rote that mistakes are rare. But history is never so simple. Memorizing recipes or cooking without them has its roots in slavery: The need for cooking aptitude predated the existence of legal literacy for enslaved kitchen workers—let alone the existence of cookbooks by free black authors.

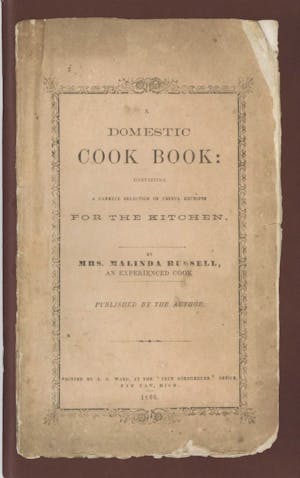

In 1866, a free black woman named Malinda Russell wrote “Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen,” a 39-page pamphlet that is considered the earliest cookbook published by a freewoman. Until 2001, however, when University of Michigan culinary history curator Jan Longone discovered a copy, it had gone unacknowledged. Before Russell’s cookbook was found, historians thought “What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Southern Living”—a 160-recipe book published in San Francisco in 1881—was the earliest African American cookbook. According to a 2013 Chicago Tribune article, Abby Fisher, the author and recipe-creator, was born enslaved and later freed; she was unable to read or write at the time of the book’s publication.

Since then, cookbooks by black authors have steadily trickled to market in far fewer numbers than titles by white authors. For context, a 2012 Cooking Light list of top cookbooks noted that more than 50,000 cookbooks had been published in the 25 years since Cooking Light had published its inaugural issue. The David Walker Lupton African American Cookbook Collection, on the other hand, is housed at the University of Alabama and contains roughly 500 publications—it’s one of the largest collections of known African American cookbooks in the country. Another one of the largest black cookbook collections in the U.S. contains just over 300 titles; it belongs to journalist Toni Tipton-Martin, whose new book The Jemima Code is a historical survey of black cookbooks and their role in black cultural preservation. Though it’s likely that black authors have published a few more cookbooks than those that have been found and preserved since 1866, many have been lost due to the vagaries of regional printing and their absence from public records.

September and October, then, have been anomalous: Including Tipton-Martin’s book, an unprecedented six cooking-related books by black women will have been published by the end of this month. Food blogger Jocelyn Delk Adams’s first book, Grandbaby Cakes, was published on September 1. On September 8, Dora Charles, who served as a chef at Paula Deen’s flagship Savannah, GA restaurant, The Lady & Sons, for 22 years, saw her first cookbook publication, A Real Southern Cook: In Her Savannah Kitchen, at age 61. Singer Kelis Rogers’s first cookbook, My Life on a Plate: Recipes from Around the World, was released on September 28. Robbie Montgomery, star of the Oprah Winfrey Network reality series Welcome to Sweetie Pie’s, published her first cookbook on October 20. Food culture podcaster Nicole A. Taylor’s first book, The Up South Cookbook: Chasing Dixie in a Brooklyn Kitchen, also published on October 20th, is a combined personal history, migration story, and recipe collection.

Though the publication of so many cookbooks by black women in such a short time is unusual, the narratives of the books are similar: They cover family, tradition and their intersection with race, class, and income. Adams’s cake recipes were adapted from her grandmother’s, who was responsible for “ringing the supper bell to assemble her daddy and 13 brothers from working in the field.” Charles, who was named in the racism lawsuit against Deen in 2013, wrote of being the descendant of slaves and sharecroppers. “There was always a fabulously good cook in my family, going right back to slavery, when both sides of my family labored on the plantations in the Lowcountry,” she writes in A Real Southern Cook.

The diversity of flavors and styles represented in these cookbooks—from the international food in Kelis’s to Taylor’s contemporary, Northern approach to Southern cuisine—should remind us that not all cookbooks by black authors cover “soul food”. In a 2007 New York Times piece on the search for Malinda Russell, Molly O’Neill wrote:

Neither the activists nor the scholars who later devoted themselves to black studies intended those dishes to be seen as the food on the stove of every black cook in America. But that is exactly what happened, historians say. [...] And then the volume by Malinda Russell surfaced. The evidence of a single cookbook is not enough to rewrite culinary history. Still, Mrs. Russell’s book suggested that a more nuanced view might be in order. Instead of rustic Southern “soul food,” it served up complex, cosmopolitan food inspired by European cuisine.

It calls to mind a passage from historian Tera W. Hunter’s 1997 book, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives after the Civil War:

[...] Cooking required the most skill and creativity. Cooking was the only household chore to benefit from technological advances in this period. [...] Most black cooks developed improvisational styles of food preparation [...]. They measured and added ingredients according to previous experience and the impulses of their imaginations. As one cook described her work: “Everything I does, I does by my head; it’s all brain work.”

The ability of this country’s earliest black cooks to retain each step and to estimate each measurement well enough for viable recipes to be preserved for generations—whether or not any written copies survived—is nothing short of incredible. Today, cooking is still brain work, especially when it comes to marketing oneself as an expert in the food market. Though published cookbooks are still considered to be a brass ring for some, other media has been especially useful in heightening black cooks’ public profile.

It’s worth noting that Grandbaby Cakes began as a blog. Taylor’s Up South Cookbook comes after years hosting the food culture podcast, “Hot Grease.” Montgomery, despite decades of successful restaurant-owning in St. Louis, scored her first cookbook publication only after three seasons of starring in a reality show that showcased her food. In an interview with KCRW’s Good Food, Tipton-Martin said, “I took this project to the internet in a blog form because I couldn’t get it published, […] and [eventually, University of Texas] Press came along and did respect the material and accepted the challenge.” For self-taught cooks like The Kitchenista Diaries creator Angela Davis and Carnal Dish owner Resha, the internet has been paramount in amassing a following. Davis, who was recently recorded for an upcoming segment of EssenceEats—Essence magazine’s culinary video series—told PBS Black Culture Connection in a 2013 interview that the culinary world is opening up for black chefs, “by way of exposure to new ingredients and techniques we may not have learned at home.”

It’s easier for black cooks to circumvent traditional cookbook publishing and share their recipes, preparation techniques, and culinary trends via online and traditional TV shows, blogs, and podcasts. This sort of technological resourcefulness may eventually become a necessity for all chefs—not just those who are self-taught or African American—and it’s heartening to see black women like Taylor, Adams, Davis and others at the forefront of the movement. After all these years, necessity is still the mother of invention for black cooks in America. Our palates continue to benefit from their ingenuity.