Czesław Miłosz famously observed, “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.” That must be doubly true when the chronicler in question is a preternaturally observant illustrator with an acid wit. The hundred-and-fifty-odd pages of Riad Sattouf’s internationally bestselling graphic memoir, The Arab of the Future: A Childhood in the Middle East, 1978-1984—the first English installment in a multi-volume series documenting the author’s frequently absurd youth split between France, Libya and Syria—move with an irrepressible comic velocity. The book is told Candide-style, through the eyes of a total innocent, Sattouf. The child of a passive Breton mother, Clémentine, and a goofy, boorish Syrian father, Abdel-Razak, Sattouf shrewdly restricts himself to the point of view of his age throughout. It is a brutally honest and efficient narrative engine that is fueled, so far at least, almost entirely at the expense of his Arab side, which is comprised of members who come across to varying degrees as violent, superstitious, prejudiced, unhygienic and irredeemably basic.

We meet young Riad in 1980, when he is two years old and his family still lives in France. Life is simple; he has long, flowing blond hair and is the center of his parents’ world. Clémentine and Abdel-Razak—the only literate member of his family and “a brilliant scholarship student” (though we never see him put his mind to use)—have been together for almost a decade at this point. However even in a flashback to their first encounter in the cafeteria of the Sorbonne, Sattouf père is drawn as a bumbling if innocuous Borat-like figure, not particularly charismatic or handsome, and either too clueless or too stubborn to acknowledge the disastrous effect he has on Clémentine and her friend, a black woman even more hostile in her response to him. As an act of pity, Clémentine shows up for a rendez-vous with Abdel-Razak and soon they are a couple. Perhaps because a child can never fully comprehend the romance of his parents, or perhaps because there is no logic here to explain, we never understand why she decided to let this happen.

Proud and hypersensitive, Abdel-Razak is plainly seduced by France—“They even pay you to be a student!” he marvels—and by extension the West, even as he bubbles with ressentiment, fancying himself, correctly at times, belittled and disrespected there. He senses racism everywhere, when he graduates cum laude from the Sorbonne, when an employment offer from Oxford University misspells his name. And he bristles at larger developments, such as Egypt’s humiliation after the Camp David Accords. Though he’s a secular man, he finds himself swept away in the fantasy of a pan-Arab cultural-political rejuvenation. (The title is an ironic reference to this idealistic belief.) In what will become a pattern in their nomadic lives, Adbel-Razak applies for jobs without his family’s knowledge or consent, and accepts one in Muammar el-Qaddafi’s Libyan regime.

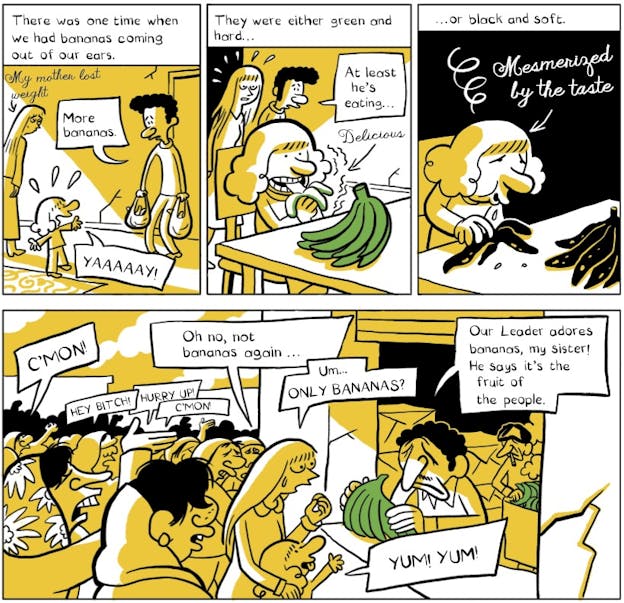

Equipped with an outsider’s eye wherever they end up, young Riad recounts his experience of Libya as a closed society that is a phantasmagoria of deprivation and ineptitude. Private property is banned, and all doors lock from the inside. As soon as the family leaves their university-provided housing for a stroll squatters swoop in. There are constant food shortages, too. Much to a toddler’s delight, they subsist at times on bananas alone. The entire society seems to operate on the whims of the larger than life Supreme Leader whose portrait is plastered everywhere and whose grand manifesto, The Green Book, Abdel-Razak now dutifully reads. Yet of all things, what bothers him most is Qaddafi’s pan-African support for blacks. An unprincipled bigot, Abdel-Razak is also a hypocrite—we recall it was Clémentine’s black friend who first caught his eye. This is the first of many subtle moments in the book when Riad eviscerates his father, who doesn’t even have the integrity to be mean. Though there can be a tenderness to his depiction—Abdel-Razak is not genuinely bad so much as impotent, his insecurity in turn leading him to habits of low-grade cruelty one can imagine he might rise above were circumstances otherwise, were there access to healthy self-esteem—it is a portrait of a man that only grows less flattering with time.

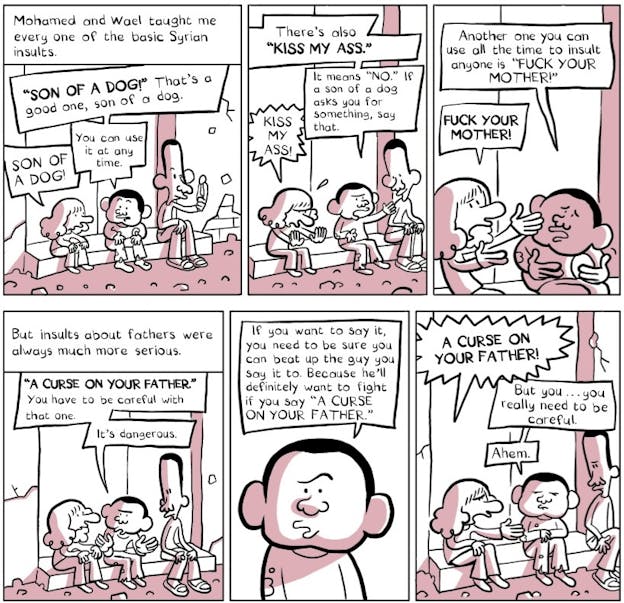

When it is announced that Qaddafi has decided teachers and farmers will swap trades, and after a stint back in France, he tricks Clémentine again, this time accepting a position in Syria under Hafez al-Assad. Now with another baby in tow, the family returns to his tribal hometown near Homs, a far more violent and cynical situation than Libya. The frustrated “other” in France, Abdel-Razak, a Sunni in a society now dictated by Alawites, a younger brother within his own clan, rarely lives up to his delusions of grandeur at home. Yet he never misses a chance to rejoice at someone else’s vulnerability or misfortune. When he encounters a childhood friend on a bus, he recalls with amusement how the man, once a promising student, was bullied out of school. But Abdel-Razak’s greatest failure—he cannot imagine another’s point of view—will become one of his son’s principle strengths. Which is why one wishes to know more about Clémentine, a seemingly reasonable woman whose underlying thought process and motivation for marrying and trailing this petty man around the globe remains opaque. Perhaps she will play a larger role in the forthcoming volumes that take place in France.

Prior to the translation of The Arab of the Future, Riad Sattouf was primarily known in the English-speaking world, if he was known at all, as the only Arab contributor to Charlie Hebdo, the fanatically irreverent satirical magazine whose staff was massacred by Islamists last January. Now a successful filmmaker, author and columnist at the mainstream weekly l’Obs, he insists he’s apolitical and barely keeps up with Middle Eastern news. This hasn’t prevented him from being criticized in France for painting an excessively negative picture of his father and the societies that shaped him—and by extension Arabs as a whole—at a time when, as Adam Shatz notes in a recent New Yorker profile of Sattouf, “defense of laïcité, the French model of secularism, has increasingly assumed anti-Muslim undertones.” But it is hard to read this book and come away with that impression. It is too personal an account; too universal an indictment of the adult world and its insidious methods of diminishment we all have either faced or been fortunate enough to escape.