Celebrities have finally figured out how to use social media. On Beyoncé’s Instagram you can find glossy photo shoot quality snaps of Queen Bey mugging in an American flag leotard (826,000 likes) but you can also find an out-of-focus candid in which she shares an intimate moment with Jay Z (898,000 likes) and three or four literal behind-the-scenes shots of Beyoncé performing in concert, the bright lights shining into the lens inappropriately from stage right. The Hollywood documentary effect has become an unconscious trend among regular people, who now strike a range of familiar celebrity-like poses on social media: Celebs in basketball shorts, models walking their expensive flat nosed dogs, blondes getting their hair curled with hot metal sticks. Even the fashionable gym leisurewear trend is a social media production. Stars pose as normal people, and we pose as stars posing as normal people.

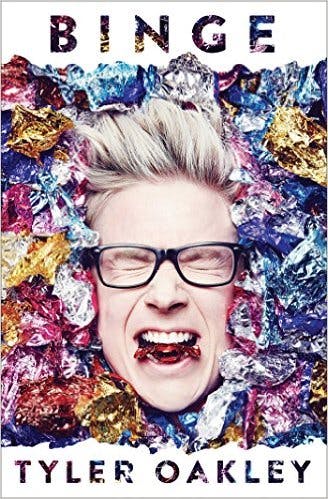

Enter: YouTube. More than any other social media platform, YouTube has the power to make stars democratically. Tyler Oakley, whose memoir Binge is released this month, is a case in point. Now 26 years old and a regular D-lister on red carpet events, Oakley grew up in Michigan as a nerdy gay kid with wire-rimmed glasses and hoodies. It’s a stark change from his pastel and bleach blonde bouffant today. Videos of Oakley from as recently as 2013 elicit YouTube comments like ‘omg fetus Tyler!’ all the time. Currently Tyler Oakley belongs to a crew of YouTubers, many of them gay, who vlog about their personal lives, celebrity fandom, and social justice issues, often while playing lo-fi Jimmy Fallon style talk show games. The result is sassy and a little fun. The reward for cultural immersion is mostly literacy in portmanteau hashtags for homoerotic YouTuber couplings.

YouTube has pioneered the behind-the-scenes aesthetic. Although there is a broad range of production quality on YouTube, almost every vlog is structured like a series of outtakes—full of jump cuts, swearing, and humorous blunders. Most successful vloggers start out using their webcam and built-in microphones, although they eventually trade up. Corporations go nuts for this stuff and try to simulate YouTube vlogging or else partner with vloggers as “influencers.” For example, L’Oreal partnered with beauty vlogger Michelle Phan to create a line of cosmetics with grassroots buzz. The very successful media company I work for has a limited-run vlog of our employees answering reader questions from bed.

Although he does not identify himself as a deep thinker (he says he’d rather watch Judge Judy than go to a museum) Tyler Oakley’s memoir registers YouTube’s fetish for behind the scenes content and plays to its audience. One of Binge’s mantras is “all the world’s a stage” and Binge definitely plays itself up as a backstage pass. Among the topics on offer are Oakley’s childhood defecation problems, physical abuse by a sexual partner, eating disorders, splintered sense of self (@TylerOakley is his alter ego), and the revelation of gay pornography. Sure, every memoir is confessional, but do most memoirs give you the backstory on their Taylor Swift lip-sync video and embed screencaptured subtweets about the author losing his virginity?

Unique to Oakley’s YouTube memoir is the way different platforms bolster each other as mutual behind-the-scenes content. Binge is a backstage pass for Oakley’s YouTube account, but his YouTube account is also a backstage pass for his book. Oakley has uploaded a ton of book trailers promising first looks, revisiting the days of Tylers past, and diarizing the author’s high levels of stress and excitement. Throughout the book Oakley embeds easter eggs for super fans, such as the secret romantic meaning of erased drawings on a chalkboard from a video in 2008 and the exegesis of a tweet about Oakley’s “arch-nemesis” which refers to a meeting with his high school musical theater rival. Tumblr, of which Oakley’s also a fan, was used as tween focus group beta testing for one of the YouTuber’s crowning achievements: getting Harry, Liam, Niall, Louis and Zayn (the boy band One Direction) to don garlands of plastic craft shop flowers for a press photo. It’s all perfectly entertaining and betrays how momentous and event-like social media has become: an entire chapter is dedicated to the behind-the-scenes of filming a boy band taking a photo that the author engineered to be gifable. This stuff really is important to a lot of people. At one 1D concert Oakley was surprised by the entire stadium cheering his name.

The irony of social media, and YouTube in particular, is that in spite of its vacuity it does so much good. YouTube is the only social media platform I can think of that pays its content creators directly. Online Marxists often slam Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook for extracting emotional and creative labor from their users without pay, but YouTube gives its content creators slightly more than half of a video’s advertising-generated revenue. This is reflected in the metaphors used to describe YouTube, which deploys the language of public utilities. In one New Yorker profile of the corporation, YouTube is a municipality, not a nation state; public access television, not cinema. (David Cohen, an executive VP at Universal McCann says advertisers were wary of YouTube at first because “its streets ‘were not clean and well lit’.”) YouTube the corporation is not politically perfect—it is owned by Google and collects metadata—but as Facebook demonstrates, it could be worse.

The content creators get political, too. Tyler Oakley belongs to one of YouTube’s greatest political movements, the push for LGBTQ rights. Quite a lot of YouTube’s most successful vloggers are gay or queer. These include Oakley, Hannah Hart, Michael Buckley, and others. Ricky Martin says Tyler Oakley’s 2008 Coming Out Day Video helped the singer make his decision to leave the closet. I’m about Tyler’s age—so a little too old to have watched Oakley’s videos when I was coming out—but in 2006 I used to watch Jonny McGovern music videos and vlogs by gay YouTubers with snakebite piercings making out in their basements. This was back when a whole episode of Will & Grace was dedicated to one male-on-male peck and almost all gay TV coverage was about trauma. Watching scenesters play same sex spin the bottle online changed my life.

One of the best ways you can read Oakley’s Binge is as an ethnography of gay millennial life. Most of us are too young to have written memoirs, so this is valuable. Like many other queers of our generation, Oakley insists on his sexuality from a young age. (“Andrew’s birthday invite said to bring a winter coat, as we’d be riding his four-wheelers (so butch—I was in love).”) Oakley comes out to his mother when he’s 11 years old and describes in minute detail the experience of finding pornography at the same rate as his dial-up could host it. For many of us millennials, gay and straight, our hormones evolved at the same rate as the internet and we had to make do with lit-erotica until internet got fast enough to stream video, though we also remember hard copy porn. Oakley still remembers the name of his favorite video. It was “Fratguys Whip Out a Ruler.”

The Bush era was a curious time to be a gay teen. Oakley describes rebuffing his father’s homophobic Christian evangelism with aplomb:

As part of their attempt to assimilate me into heterosexual teenage-boy culture, they got me a subscription to Breakaway— a magazine for teen guys published by the antigay group Focus on the Family. It featured Christian guys talking about their intimate relationships with God and had in-depth articles about how to deal with the temptations of sin. I eagerly anticipated every edition, but only for the fitness section: hot Christian guys showing workout techniques. I definitely sinned every month to that page. Ten more Hail Marys!

Is enjoying porn political? In fact, YouTube’s is a very millennial gay conundrum. On the one hand, it idolizes celebrity culture, vacuous spectacle, and hyperbole. It is often anodyne; for example, YouTube’s terms of service prohibit acts such as nudity and copyright infringement. On the other hand, YouTubers, with others, spearheaded the most successful social movement in a century. Dan Savage and his partner Terry Miller’s It Gets Better Project was an important step in calling attention to anti-gay bullying, and it’s hosted on YouTube. According to their website, It Gets Better videos have been viewed over 50 million times. The Trevor Project, the confidential suicide hotline for LGBT teens, was founded in 1998 but didn’t get a serious boost until the late 2000s. Its largest individual donor is...Tyler Oakley. Likewise, many videos documenting homophobic bullying have been uploaded to YouTube as catalyst for progressive invective.

Much of this is an effect of the feminist and queer politics that urges “the personal is political.” What constitutes politics when your body, gesticulations, and voice are visibly queer? Sometimes the end effect is radical (for example, the higher visibility of trans people of color), but sometimes it means that shooting the shit about Lady Gaga for an online video seems like radical politics, which,to me, is not. And where would you place a viral video of a fat butch lesbian of color dancing in a watermelon bra on that spectrum?

Binge unintentionally references the strange place queers and the YouTube community occupy in radical politics with its very first line:

Go ahead, binge. I’m not saying go out and snort a bunch of cocaine or do anything that’s going to seriously put you or the people around you in danger, obviously.

Live dangerously, but not too much. In so doing, YouTube risks inserting itself into the boring corporate tradition of using facile moralizing to fill out otherwise vacuous and genuinely fun content. “Doddisms” by the Mickey Mouse Club’s Jimmie Dodd—which were morals tacked on to the advertorial Mickey Mouse Club’s musical numbers—come to mind. Tween ensemble cast variety shows like the Zoom and the Mickey Mouse Club are a definite inspiration for YouTube content, although they influence corporate accounts like Buzzfeed Video’s Try Guys more than they do independent vloggers.

Anyway, who said YouTube ought to be political? Well, YouTubers did. That’s what makes YouTube so compelling and so infuriating. When we’re all annotating our own celebrity (aided by genuine celebrity’s affection for appearing just like us), it’s difficult to distinguish between cases where the personal really is political and cases where that motto is appropriated for personal and uncritical gain. Now that movie and pop stars have become good at social media and can make themselves more personal than ever, the simpatico between celebrity culture and feminist/queer “the personal is political” politics is stronger than ever.