In a prominent national magazine, there appeared an indictment of the late Henry D. Thoreau whose literary stock the indictment’s author judged to be grossly overvalued. It wasn’t just Thoreau’s writing that deserved a take-down; so did the man himself, if in Thoreau’s case one could even distinguish between the two. Thoreau was conceited, indolent, egotistical. Also: a failure, selfish, self-involved, useless, unimaginative, provincial. The indictment compared Thoreau to Montaigne—unfavorably; called him a sophist, a hypocrite, a humorless boor.

He’d spurned humanity’s company, preferring “the society of musquashes,” and therefore didn’t know anything about the mass of men and their quiet desperation. He was a narcissist who looked out at the world and saw his own reflection. He had an unhealthy mind but went about prescribing medicine to others. He was forever nattering on about getting away but remained close to home his entire life. The world did not esteem him as highly as he esteemed himself. The world’s low esteem for him could be measured by the low sales figures of his books. True, Thoreau could turn a phrase, especially when it came to imagery and metaphor. Begrudging compliment paid, the condemnation resumed: Thoreau played at rugged self-sufficiency while squatting on borrowed land, in a house built with a borrowed axe.

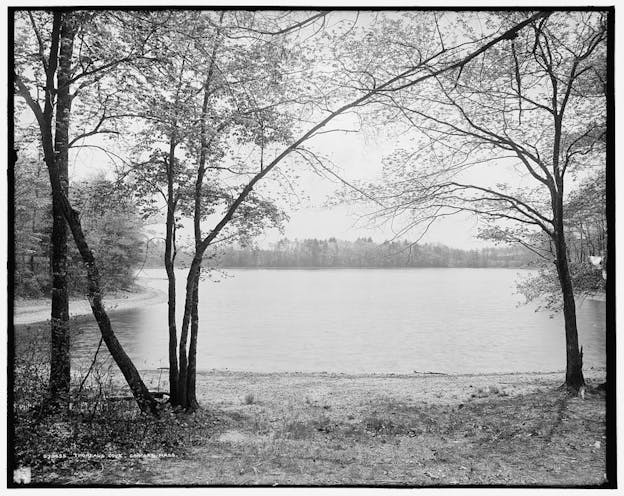

There is one charge omitted by the indictment’s otherwise thorough author—James Russell Lowell, writing in The Atlantic Monthly in 1865, when Thoreau’s grave was still fresh. Lowell neglected to mention everyone’s favorite incriminating biographical factoid about Thoreau: that during the two years he spent at Walden Pond, his mother sometimes did his laundry.

“There is one writer in all literature whose laundry arrangements have been excoriated again and again, and it is not Virginia Woolf, who almost certainly never did her own washing, or James Baldwin, or the rest of the global pantheon,” the essayist Rebecca Solnit observed not long ago. “Only Henry David Thoreau has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.”

Last week, as if to celebrate the sesquicentennial of Lowell’s indictment, a new one appeared in The New Yorker under a funny title, “Pond Scum.” Its author is Kathryn Schulz, a science writer and environmental journalist—among our generation’s best. Perhaps because science writers and environmental journalists are expected to revere Thoreau, and perhaps because many actually do, Schulz presents her new indictment as a heresy, one that aims to deliver a bracing corrective to the prevailing and puffed-up opinion of America’s original nature boy.

On Twitter she joked that she’d need to go into witness protection, that’s how heretical her heresy was. When the vendetta of Thoreau fans failed to materialize the way Gatsby fans had in response to a previous essay she’d written, she tweeted: “In a rumble between the rabid Gatsby fans and the rabid Walden fans, the Gatsby fans would win. (More of them, and sharper knives.)” On my Twitter stream, you’d think rabid Walden fans would be somewhat more populous than on Twitter’s high seas. I’ve quarreled with Thoreau in print—and far more often, in my head—but I’ve also mined his prose for epigraphs, and I’ll confess, shamefully, that I once tweeted a line of his—“Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough. #thoreau #metatweet”—that no one retweeted or favorited (sad emoji). But to my surprise, even on my Twitter stream, the responses to Schulz’s axe job were mostly gleeful.

“This is the Thoreau takedown I have been waiting for my entire life. Thank you,” tweeted one of my favorite twitterers. “First, they came for Atticus Finch. Now, Thoreau? Brilliant,” tweeted another. To which I initially responded with quiet desperation, while listening to a different drummer in the distance. I am far from jesting (wink emoji).

I can think of a few explanations for the failure of Thoreau fans to materialize, armed with flutes and truly excellent pencils instead of daggers and shivs, but the explanation I find most plausible is this: Schulz’s heresy turns out to be more orthodox than she thought.

It’s true, few people actually bother to read Thoreau anymore. And Schulz is right that those who revere him without reading him, preferring to sample him aphoristically on inspirational posters, have simplified both him and his work beyond recognition. But Schulz does the same, replacing the distortions of hagiography with those of caricature, and the caricature has been drawn before, by James Russell Lowell and many others since.

Here, several years ago, is Jill Lepore, also writing in The New Yorker: “one senses that [Thoreau] preferred jail to a cabin crowded with visitors.” He “loved his solitude (a friend of his once said that he ‘imitates porcupines successfully’), and he hated hearing news. . . . Above all, he cherished his manly self-sufficiency (even though he carried his dirty laundry to Concord for his mother to wash).”

Here’s Bill Bryson, reassuring the readers of A Walk in the Woods that despite his own concerns about the environmental degradation to be witnessed along the Appalachian trail, he’s no Thoreau, whom he dismisses as “inestimably priggish and tiresome.”

Here’s Garrison Keillor in a syndicated column, presenting to the above-average children of Lake Wobegon a comforting portrait of the below-average hermit of Walden Pond:

A sorehead and loner whose clunky line about marching to your own drummer has found its way into a million graduation speeches. Thoreau tried to make a virtue out of lack of rhythm. He said that the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. Okay, but how did he know? He didn’t talk to that many people. He wrote elegantly about independence and forgot to thank his mom for doing his laundry.

The caricature has been drawn so many times and so redundantly that Robert Sullivan spent an entire book, published in 2009, trying to excavate Thoreau from beneath the encrustations of both unflattering and beatifying hearsay. The Thoreau You Don’t Know, Sullivan’s book is called. I recommend it, though Sullivan’s effort, like Solnit’s, seems to have been a futile one.

For now here comes Schulz, touching up the old cartoon. She doesn’t mention Thoreau’s mother doing the laundry, perhaps because she doesn’t have to. She gives us her cookie-baking instead. “The real Thoreau,” she writes, as if channeling Lowell, “was in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself to understand and thrive in the world.” He was a hypocrite, and Walden a sham piece of “cabin porn,” since he wasn’t really roughing it—not like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Ma and Pa, homesteading and churchgoing on territory recently vacated by the heathens, building a little house on a stolen prairie. (My immigrant ancestors did the same.)

So far as frontier literature goes, at least for grown-ups, I’d take Cather over Wilder, but the more salient point is that Thoreau knew full well the difference between a suburban woodlot and the wilderness. In The Maine Woods, after returning to Concord from a trek to Mount Katahdin, he expresses his preference for “partially cultivated country.” At Walden and in Walden, he was playing at roughing it, Schulz is right about that, and playing at much else, too—farming and bookkeeping, for instance. Right there, in Walden’s opening paragraph, he locates the pond in the town, and a few paragraphs down says he’s traveled widely in Concord—which is a kind of joke.

Thoreau’s contemporaries didn’t like him, Schulz tells us, relying presumably on the testimony of one of his Harvard classmates, John Weiss, who went on to become a minister and a writer who would likely be mostly forgotten now were it not for his portrait of his former classmate, with whom he was only casually acquainted. Weiss defended Thoreau’s unorthodox religious views from critics, but he also made much of Thoreau’s cold demeanor and clammy hands; also, his ugly, big-nosed physiognomy. (It’s true, Thoreau was a homely man, and knew it.) In her essay on Thoreau’s laundry, Solnit quotes a first-hand impression of Thoreau, written by the abolitionist Daniel Conway after Thoreau and his sister broke the law by sheltering a fugitive slave. Conway’s character sketch bears repeating far more than do the collegiate memories of a classmate Thoreau hardly knew:

In the morning I found the Thoreaus agitated by the arrival of a colored fugitive from Virginia, who had come to their door at daybreak. Thoreau took me to a room where his excellent sister, Sophia, was ministering to the fugitive. . . . I observed the tender and lowly devotion of Thoreau to the African. He now and then drew near to the trembling man, and with a cheerful voice bade him feel at home, and have no fear that any power should again wrong him. The whole day he mounted guard over the fugitive, for it was a slave-hunting time. But the guard had no weapon, and probably there was no such thing in the house. The next day the fugitive was got to Canada, and I enjoyed my first walk with Thoreau.

How to reconcile Conway’s firsthand Thoreau with Schulz’s secondhand one?

Like Lowell, she presents the sales figures of Thoreau’s books, published “to middling critical and popular acclaim,” as a measure of their value and of their unlikeable author. Let the record show: Whitman, whom Schulz compares favorably to Thoreau, fared worse, for whatever that’s worth—not much, I’d say. The initial print run of Leaves of Grass sold just 795 copies to Walden’s 2,000. Both books have made up for it since.

Of the many charges her indictment levels against Thoreau, the one Schulz gives greatest weight is the charge of Puritanical misanthropy. “Food, drink, friends, family, community, tradition, most work, most education, most conversation: all this he dismissed as outside the real business of living,” she writes. Biographically, she is mistaken on pretty much every count.

“One misperception that has persisted is that he was a hermit who cared little for others,” says Elizabeth Witherell, who has spent a few decades editing a critical edition of Thoreau’s collected works. “He was active in circulating petitions for neighbors in need. He was attentive to what was going on in the community. He was involved in the Underground Railroad.” He quit his first teaching job, in protest, because he was expected to administer corporal punishment, and struggled to find a new one. He loved watermelons, and threw an annual watermelon party for his friends, of whom he had plenty. Children were especially fond of him. Sophia and Thoreau’s mother were founding members of the Concord Women’s Anti-Slavery Society, and Thoreau invited them to convene at least one meeting that we know of at his cabin in the woods, to celebrate the anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the Indies. As for family, he lived most of his life in his parents’ boarding house, paying rent and helping out as a handyman. He was very handy. He could dance, and play music. He wrote lovingly about his father, mother, and siblings in his journals, and they wrote lovingly about him, and he was so devastated by his brother’s death that he developed symptoms of tetanus in sympathy.

Schulz mentions Thoreau’s visits home, and the visits he received, but accuses him of downplaying them in Walden while overlooking the chapter devoted to that subject, “Visitors,” which includes this famous passage: “I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society. When visitors came in larger and unexpected numbers there was but the third chair for them all, but they generally economized the room by standing up. It is surprising how many great men and women a small house will contain. I have had twenty-five or thirty souls, with their bodies, at once under my roof, and yet we often parted without being aware that we had come very near to one another.”

Schulz describes Thoreau as “well off.” His biographer, Walter Harding, says the Thoreaus often lived in poverty. Who’s right? Perhaps both, depending what you mean by “poverty” and “well off.” In Thoreau’s later years, after the family pencil business succeeded, with his help, they secured a place in Concord’s middle class, but for most of Thoreau’s short, tubercular life, they were financially insecure. The portrait he draws in the opening paragraphs of Walden of a poor laboring man reduced to mindless, mechanical toil while pursued by creditors bears some resemblance to his own father, a failed grocer who supposedly sold his wedding ring to pay his debts while neglecting to collect those of his customers. The family turned their home into a boarding house because they had to.

At Harvard, which back then was still mainly a professional school for ministers, lawyers, and teachers, Thoreau interrupted his studies periodically to earn his tuition. The seeds of Walden were sewn in the wake of the Panic of 1837, during a period of financial turmoil and rising inequality, when New England’s agrarian economy was vanishing, giving way to industrialism. Sullivan tells us that shortly before the panic struck, 63 percent of Concord’s citizens owned no land, and “about fifty men”—in a town of 2,000—controlled half the wealth. The freedoms promised by the Revolution seemed increasingly jeopardized by the marketplace. In the textile mills, the mass of men—and women—did indeed lead lives of quiet desperation, as Thoreau would have known. His friend, Orestes Brownson, was one of America’s first labor agitators. Even college graduates had a hard time finding work. There’s a reason Thoreau addresses Walden to “poor students.”

How to live in America with the intellectual freedom of a Montaigne but without Montaigne’s rank and wealth? How to study the cosmos with the ardor and insight of a Humboldt but without a boat ticket or a patron? The answers were, for a poor student, even a white and male one, no more obvious then than they are now, especially if you happened to be a poor student whose conscience was troubled by your country’s dependence on slave labor in the South and on industrial exploitation in the North. What was a poor student to do? Go West?

That was one option, availed by many, among them Laura’s Pa, who gave his darling “half-pint” some truly bad advice. And if you objected to the land grab in the West? What then was a poor student to do? Despair? Quietly? Suck it up? While minding your own business? Thoreau’s advice to poor students is not so different from Grace Paley’s: “If you want to write, keep a low overhead.”

Like many caricaturists before her, Schulz doesn’t distinguish much between the work and the man, but the “I” of Walden is a persona, one that Thoreau adopts for reasons more rhetorical than autobiographical. His “I” is in many ways akin to the speaker in a Dickinson poem, and like Dickinson, who’d read and admired him, he tends to write in riddling metaphors. He thought of Walden as a poem, in the Greek sense of that word, not nonfiction, a genre and label that did not then exist. Solnit aptly describes Thoreau’s cabin as “a laboratory for a prankish investigation of work, money, time, and space by our nation’s or empire’s trickster-in-chief.” It’s almost always a bad idea to take him too literally, as Schulz repeatedly does. “Thoreau regarded humor as he regarded salt, and did without,” Schulz informs us—a good line, if it were true.

In Walden Thoreau provides two of his favorite recipes—for “green sweet-corn boiled with salt” and bread made from “Indian meal and salt.” He relished the seasoning of humor even more. In many of Walden’s most outlandish or seemingly ridiculous passages, Thoreau was kidding, employing hyperbole and metaphor and wordplay for satirical and, yes, humorous effect. Some of his contemporaries, at least, got the jokes.

Before it appeared as the first chapter of Walden, Thoreau delivered “Economy”—“dry, sententious, condescending,” too long, is how Schulz describes it—as a well-attended lecture at the Concord Lyceum. According to a review that appeared in The Salem Observer, the lecture created “quite a sensation.” It “was done in an admirable manner, in a strain of exquisite humor, with a strong under current of delicate satire against the follies of the times.” It kept the audience, the reviewer notes, “in almost constant mirth.” After attending one of Thoreau’s lectures, Emerson recorded in his journal, perhaps enviously, “They laughed till they cried.”

Where are the jokes? In plain sight. Schulz even quotes some of them, for instance in this passage, on his objection to doormats: “As I had no room to spare within the house, nor time to spare within or without to shake it, I declined it, preferring to wipe my feet on the sod before my door. It is best to avoid the beginnings of evil.” That last sentence is a parody of a Puritanical sermon, not a sincere emulation of one, just as Thoreau’s fastidious bookkeeping is a satirical parody of business. Throughout Walden but especially in “Economy,” Thoreau is mocking the usual sources of Yankee common sense—newspapers, sermons, but especially the language of commerce—irreverently turning the platitudes and the clichés inside out and upside down.

He even indulges in a little bathroom humor. He makes fart jokes about beans. Describing his long walks, he writes, “I have watered the red huckleberry, the sand cherry and the nettle tree, the red pine and the black ash, the white grape and the yellow violet, which might have withered else in dry seasons.” Is this Thoreau piously boasting that he walks around like some American St. Francis with a watering can tending the tender sprigs? No, it’s him with a satirical mask on saying that he walks around pissing—charitably, virtuously, industriously—on trees and bushes. Without letting the satirical mask slip, he expresses mock surprise that, despite his sincere effort to “mind [his] business,” his business being pissing on bushes and trees, his townsmen “would not after all admit me into the list of town officers, nor make my place a sinecure with a moderate allowance.” He is, in the Shakespearean sense, playing the fool.

Perhaps the most curiously contrary charge Schulz levels against Thoreau is incuriosity. Provincial, yes—in his travels. In his reading, he was cosmopolitan. But incurious? The man was endlessly investigating phenomena both natural and human. On his provincial travels in Concord but also to Cape Cod and Maine, he was endlessly interviewing strangers—lumberjacks, oystermen, farmers. He romanticized Native Americans as noble savages, and exoticized them, representing the broken English of those he met phonetically in ways that now make us cringe, but unlike most of his contemporaries, he also made a point of meeting them, interviewing them, traveling with them, and he tried to learn of and from them on his long walks.

The data he collected at Walden pond is still used by climate scientists, and he sent some 900 different plant specimens he’d collected, as well as animals, to the Swiss-born Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz. My own favorite biographical vignette about Thoreau is this one, from an essay by Guy Davenport: The Thoreau who befriended Agassiz, Davenport writes, “was a scientist, the pioneer ecologist, one of the few men in America with whom [Agassiz] could talk, as on an occasion when the two went exhaustively into the mating of turtles, to the dismay of their host for dinner, Emerson.”

Curiosity is what drew Thoreau to the shipwreck he writes about in Cape Cod, Exhibit A in Schulz’s indictment. Death was yet another phenomenon he sought to understand by studying it up close. Quoting one passage out of the many paragraphs Thoreau devotes to the seaside carnage he witnessed, Schulz pegs him as a heartless bastard, a sort of Transcendental sociopath, indifferent to suffering. “On the whole,” that passage begins, “it was not so impressive a scene as I might have expected. If I had found one body cast upon the beach in some lonely place, it would have affected me more.” He’s describing here a paradox that we’ve all surely experienced: when the sufferings of strangers multiply, they have a way of growing abstract in our imaginations, as do the feelings they elicit, hence the numbed indifference casualty statistics can induce, whereas the suffering of a single individual can move us easily to outrage or tears. We saw this paradox illustrated last September by a photo of another drowned refugee who died seeking sanctuary, Syrian rather than Irish this time, a three-year-old, Aylan Kurdi, on the Greek island of Kos rather than on Cape Cod.

To turn her one incriminating passage into evidence of Thoreau’s misanthropy, moreover, Schulz has to ignore the rest of the chapter, originally published as an essay in Putnam’s. It is a kind of extended prose elegy, written to bear witness to and make sense of the tragedy that befell that shipload of Irish immigrants. Upon arriving at the beach, Thoreau memorializes the dead, and individualizes them, and makes us see them in prose as graphic, almost, as a photograph but more eloquent:

I saw many marble feet and matted heads as the cloths were raised, and one livid, swollen, and mangled body of a drowned girl,—who probably had intended to go out to service in some American family,—to which some rags still adhered, with a string, half concealed by the flesh, about its swollen neck; the coiled-up wreck of a human hulk, gashed by the rocks or fishes, so that the bone and muscle were exposed, but quite bloodless,—merely red and white,—with wide-open and staring eyes, yet lustreless, dead-lights; or like the cabin windows of a stranded vessel, filled with sand.

The essay is almost the inverse of what Schultz takes it for: not a symptom of cold indifference, an antidote to it. The stoicism of the passage she quotes is also explained by what follows it, a homily on the consolations of the afterlife. “All their plans and hopes burst like a bubble! Infants by the score dashed on the rocks by the enraged Atlantic Ocean!” Thoreau exclaims, and then reassures his readers—and, one senses, himself—that the souls of the drowned have reached the safe harbor of heaven.

It’s here, at such moments, that my own objections to Thoreau tend to arise. When he goes sauntering to the holy land, I have trouble following him there. For all his irreverence toward the church, for all his open-minded, influence-seeking study of eastern and western philosophy, he is a profoundly Christian writer, and one whose faith is, on the page at least, less conflicted than Dickinson’s or Melville’s.

It’s not, as Schulz asserts, that Thoreau wished to retreat to some prelapsarian Eden. The Transcendentalist heresy was to reject the doctrine of the Fall entirely. We are not innately fallen, and Eden is all around us, Thoreau and Emerson believed. You didn’t have to seek divinity in a church. You could find it anywhere—in the mating habits of turtles, at the scene of a shipwreck, in pond scum—if you knew how to look and listen, and at looking and listening Thoreau, the apprentice, surpassed his master. “The morning wind forever blows, the poem of creation is uninterrupted; but few are the ears that hear it,” Thoreau writes in Walden, paraphrasing Christ. I do not believe in intelligent design, or that divinity infuses the cosmos, and yet Thoreau’s artful efforts at revelation in Walden do have the power to make both time and place seem numinous, which is its own consolation. He influenced Proust and Marilynne Robinson as well as Gandhi, after all.

Schulz rightly notes that Thoreau’s theology underpins the political philosophy he articulates in “Resistance to Civil Government.” Like Gandhi, MLK, and yes, Kim Davis, he believed in higher laws deriving from a higher power, which does make his political philosophy—and Gandhi’s, and MLK’s—problematic for those of us who don’t. And Schulz is right, too, that in that essay’s provocative opening paragraphs, though less so as he goes on, Thoreau can sound like a utopian anarcho-libertarian. But to twist his protest against the crime of slavery and the illegal invasion of Mexico into the actions of an egotistical acolyte of the godless Ayn Rand, an acolyte who also nonetheless suffers from a god complex and an antipathy to Industry, is a feat of contortionism as well as contrarianism.

A few paragraphs in, Thoreau clarifies his position. It’s not “no government” that he wants but “a better government,” which is reasonable enough, considering the shortcomings he identifies. “Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them,” he asks, “or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?” That is a genuinely difficult moral question, one that is with us still. Recall that those unjust laws would soon include the Fugitive Slave Act, the prohibitions of which were being fiercely debated when Thoreau went to jail. Every participant in the Underground Railroad chose transgression over obedience. What would Schulz have had them do? Obey?

Recall, too, that people went to prison to attain the rights Kim Davis considers sacrilegious. That Davis also chose transgression does not absolve us from confronting such choices ourselves, and neither should it spare Davis from the consequences of hers. The government to which she’s beholden should not let her abuse the powers of her office; that would only exemplify the sort of abuse that worried Thoreau. Let the marriages proceed. But let her go to prison and share her opinions with those who care to listen. Transgression, for Thoreau, is not the end in itself. The opposite. It is, he argues, a “beginning.” And it is, Schulz’s assertion to the contrary notwithstanding, a deeply democratic gesture. Quoth: “Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight.” The purpose of civil disobedience as of “Civil Disobedience” is to persuade; to shift the needle on the nation’s moral compass, and in the case of gay marriage the needle is moving swiftly away from Davis, not toward her.

As I’m writing this, Bill McKibben is getting himself arrested at an Exxon station. And now I’m thinking, Why am I not doing the same? And now I’m thinking, I’m the one in need of an apologist, not Thoreau. Which is what civil disobedience can do: disturb those of us who assent, but silently, and rouse us from our quiescence. Thoreau doesn’t “intuit” his reasons for transgressing, as Schulz asserts, or simply dial up his private line to God. Yes, he believes the angels are on the side of the Abolitionist cause, justice, too, and history, but he also builds the case, subjecting his own thinking to “logical scrutiny,” laying his reasoning out.

Nor is it at all fair to say, as Schulz does, that “Thoreau never understood that life itself is not consistent—that what worked for a well-off Harvard-educated man without dependents or obligations might not make an ideal universal code.” In “Resistance to Civil Government,” he underscores and wrestles with precisely that difference. A number of his abolitionist neighbors, he writes, are afraid to transgress for fear of “the consequences to their property and family.” He sympathizes with them so fully he imagines himself in their place: “[I]f I deny the authority of the State when it presents its tax bill, it will soon take and waste all my property, and so harass me and my children without end. This is hard.” Yes, it is, and Thoreau does not shy from the difficulty.

And he himself is difficult. To my mind the better question to ask about Thoreau isn’t why we love him, because most of us don’t. Most of us ignore him, and a large number of those who pay him any mind seem to loathe him, or find him ridiculous. At the high school where I once taught American literature, Walden is no longer on the syllabus, nor is Gatsby, for that matter, and although the sample-size is unscientific, as best I can recall, not one of the adolescent New Yorkers I forced Walden on cottoned to it. The better question, or at least the harder one for me, is why it is that ever since his untimely death in 1862 we’ve been having this same argument. Saint or fraud, idol or arrogant prick: why do we seem to need him to be one or the other?

He was flawed, full of contradictions, and in Walden endeavored to document the changing seasons of his thoughts and moods as painstakingly as he did the depths and temperatures of Walden. So he liked trains, and also didn’t. My feelings about air travel and iPhones are similarly conflicted. He was of his time, and of his place, and worked hard to attain a vantage from which he could perceive both. “Who are we? Where are we?” he once asked because for him those questions were both excellent and inseparable. He sometimes sounds like a libertarian, sometimes like a progressive, sometimes like a conservative, conflicted as he was about tradition and change. He wrote so much and so contradictorily—he was an essayist, in other words—you could probably cherry pick a quote to recommend him for membership in the John Birch Society, the Communist Party, the Chamber of Commerce, or the Weather Underground if you wanted to. He had old-fashioned, stoical ideas about manliness and prized it a bit overmuch, but he also considered Margaret Fuller a soul mate.

And he was a poor student who once lost a hound, a bay horse, and a turtle dove and spent his whole life searching for them; a moral philosopher; a patriot and a dissident; a prose stylist so exquisite Dickinson, Frost, Tolstoy, Proust, Carson, Robinson, Dillard, and Schulz admired his sentences; who tried his best to live and write deliberately, and succeeded better than most; an epic perambulist and a committed abolitionist; a sufferer of tuberculosis from his youth to his death who nevertheless ascended Mount Katahdin; a naturalist who studied a pond, scum and all, so curiously and attentively he glimpsed an ecosystem and perhaps even a cosmos through the distorted mirror of his own reflection. “I am not worth seeing personally—the stuttering, blundering, clod-hopper that I am,” Thoreau, the indicted egotist, once wrote. Why can’t we take him at his word?