Two years ago, it seemed as if the the Man Booker Prize was out to conquer the world. In 2013, it was announced that the field of the world’s second most prestigious literary prize (the most prestigious literary prize was awarded last Thursday) would expand to include any work that had been published in English in the UK that year—previously, it had been limited to works by authors from the UK, Ireland, Zimbabwe, and the British Commonwealth.

Of course, the British Commonwealth includes nearly every former territory of the British Empire, so this rule change effectively only brought one major player into the fold: the United States. At the time, the chairman of the Man Booker board of trustees Jonathan Taylor turned heads when he said that keeping Americans out of contention for the prize was “rather as if the Chinese were excluded from the Olympic Games.” The decision was widely and immediately controversial—critics argued that it watered down the Prize by further excluding small publishers and unknown authors and by deviating from its fundamental Britishness—but two years later, there isn’t much criticism for the Man Booker, even though five Americans made the thirteen-strong longlist, though there isn’t much praise either.

Changes made to the Man Booker International Prize earlier this year also speak to the wider ambitions of those administering the Man Booker Prizes. Created in 2003, The Man Booker International Prize was intended as a kind of lifetime achievement award, honoring an author’s entire body of work, and was open to any author of any nationality, so long as their writing had been published in English; unlike the Man Booker Prize, works in translation were admissible. Past winners include Ismail Kadaré, Chinua Achebe, Alice Munro, Philip Roth and Lydia Davis—an international, if very European, list. (There is perhaps no contemporary writer more Continental than László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian author who was honored earlier this year. Munro is Canadian but could be English; Roth is American but could be Czech; I’m still not quite convinced Lydia Davis isn’t French.) In July, it was announced that the Man Booker International Prize, which had been previously awarded biennially, would be given out annually, beginning in 2016, and that it would be merging with the Independent Fiction Prize. More importantly, it would no longer be awarded in recognition for an author’s entire body of work, but to the best translated book published in English that year: no more Davis, no more Roth, no more McEwen or Munro.

Taken together, these changes have made the Man Booker Prizes truly international—an attempt to award the best English language work every year and the best writers working in or being translated into English. It would be tempting to say that this was the point all along—that those who administer the Man Booker Prize recognized that in a hyper-connected age, a writer’s nationality may matter less than it once did, and that the awards were changed to reflect that. This may have played a role in the decision to expand the prizes, but it doesn’t appear to be the sole motivating factor. Instead, the impetus for these changes seems to stem from the decisions made by the administrators of another award: the Folio Prize. The Folio was first announced in 2013 as the first English language prize open to writers of any nationality—in effect, when the Man Booker Prize expanded its parameters, it was seeing the Folio’s bet; when they announced the changes to the Man Booker International Prize in 2015, they were raising it.

It’s also not unreasonable to assume that the changes made to the Man Booker Prizes had less to do with readers than they did with corporate sponsors: starting in 2013, the Man Booker Prize was not only competing for attention from the public with the Folio Prize—it was competing for attention from potential corporate sponsors. Literary prizes are prestigious, but the good ones are expensive—when the Folio Prize invaded the Man Booker’s turf there may have been a sense of existential threat, which would help explain many of the changes the prize has undergone over the past two years.

If the Man Booker and Folio prizes were engaged in a kind of low-stakes cultural cold war, it was a short one. On September 30, the Folio Prize announced that it had been unable to find a sponsor for 2016 and that no prize will be awarded for that year. The Folio Prize hopes to return, but there’s no doubt that its future is in jeopardy.

Still, the Man Booker Prize is in something of a curious position. It has, to the best of my knowledge, the broadest scope of any literary prize being awarded today—without the Folio, it certainly has no competition in the “Best English Language Novel” department. But its rapid expansion has changed the character of the prize. Complaining about the Man Booker Prize is something of a tradition in England—charges of corruption are particularly popular and, it seems, often valid—but many people I’ve spoken to in the British publishing industry have seemed tepid about the prize since Americans were allowed to compete for it. Complaints have turned into shrugs. The American press has undoubtedly given the prize more attention since it started to allow Yanks, but few seem to think of it as an international prize akin to the Nobel. (Or, for that matter, akin to the Booker International Prize, whose rebranding has managed to tighten the award’s mission.) That may be because it has retained its fundamental Britishness, even as its expanded—it’s an award for best English language novel, but one that encompasses the former British Empire, and one clearly awarded by the British. (I suppose a comparison could be drawn to the Oscars, whose American focus is apparent.) At the moment, however, the prize feels somewhat liminal—both not quite British and too British at the same time. The Man Booker has expanded for two years, but now that it’s alone at the top of the heap, it has what may be a more difficult challenge: convincing the world that it’s a global prize, not a British one.

With that in mind, here’s a brief preview of the 2015 Man Booker Prize, which will be awarded on Tuesday.

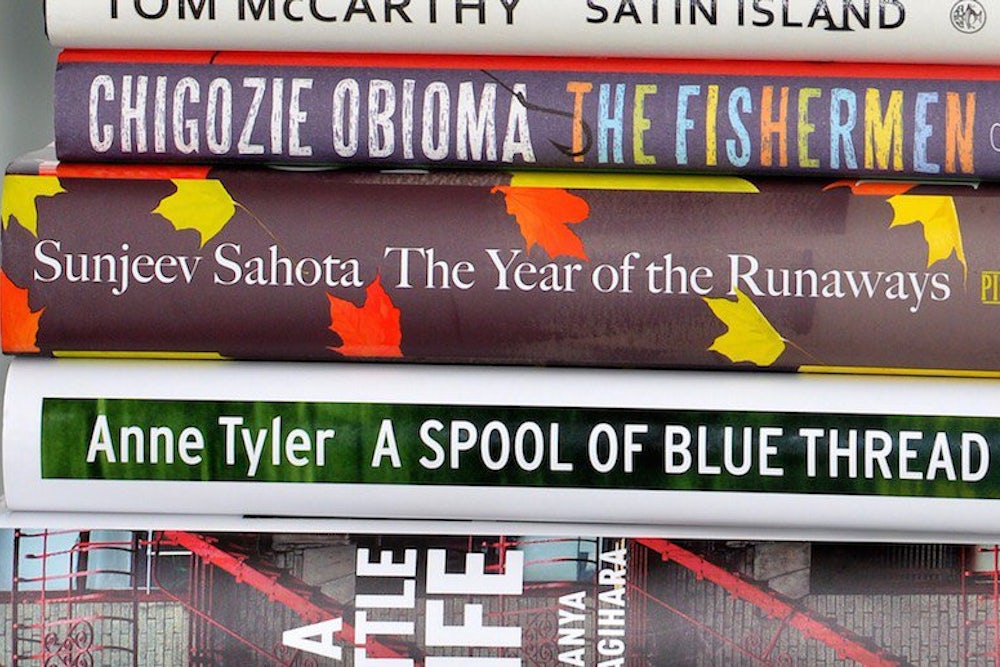

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

(American; 6/2 Ladbrokes odds)

Described (in a takedown review) by Christian Lorentzen as “a male millennial take on Mary McCarthy’s The Group,” A Little Life is the current Ladbrokes favorite. The novel follows the friendship between three men over the course of over three decades. It’s an unabashedly melodramatic novel—if there was a Man Booker Prize for Tears, it would have already won. While it may be the betting public’s choice, it hasn’t just split critical opinion, it’s dumped ice cream all over it and dropped a cherry on top, to paraphrase Andy Zaltzman. It’s a novel that people seem to either love or hate and I suspect that fact will keep it from winning the Booker. Also, oddsmakers apparently don’t reduce fractions.

The Year of the Runaways by Sunjeev Sahota

(British; 5/2 Ladbrokes odds)

This novel follows two Indian men who fled their home country for Sheffield, England, where they share a rundown house with nine other Indian emigrants. According to the Telegraph, which praised the novel's social observations, “it relates the exploitation of Indian illegal labourers in Britain, a whole invisible underclass of “faujis.” In the time-worn pattern of the immigrant novel, recent arrivals search for work, lose some of their greenness and find their way in a new city.”

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James

(Jamaican; 7/2 Ladbrokes odds)

My pick to win the 2015 Man Booker Prize. A panoramic and multivocal fictional oral history of three decades of Jamaican history, A Brief History of Seven Killings begins with the 1976 attempted assassination of Bob Marley. A cool and contemporary Rashomon, The New York Times’s Michiko Kakutani wrote that the novel was “like a Tarantino remake of The Harder They Come but with a soundtrack by Bob Marley and a script by Oliver Stone and William Faulkner, with maybe a little creative boost from some primo ganja.” Kakutani clearly had her heart set on the back cover of the paperback edition when she wrote that, but she’s not wrong.

A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler

(American; 10/1 Ladbrokes odds)

The other American on the shortlist, Tyler was also longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2011. An epic that spans seven decades, A Spool of Blue Thread received some pushback from critics, who found it to be a somewhat cliched account of an American middle-class family. Still, writing in The New York Times Book Review, Rebecca Pepper Sinkler praised Tyler for...well, transcending cliche: “[Tyler’s] great gift is playing against the American dream, the dark side of which is the falsehood at its heart: that given hard work and good intentions, any family can attain the Norman Rockwell ideal of happiness—ordinary, homegrown happiness.” The Man Booker Prize will go to an American eventually, but don’t expect it to happen this year.

The Fishermen by Chigozie Obioma

(Nigerian; 10/1 Ladbrokes odds)

The only debut on the shortlist, The Fishermen has been praised by many critics for its “mythic” qualities and tracks the relationship between four brothers after a local madman known for his prophetic abilities tells them the oldest will be murdered by one of the other three. “There is very little light in The Fishermen,” writes NPR's Michael Schaub, “it's a relentlessly somber book that still manages to pull the reader in even as it gets more and more melancholy.”

Satin Island by Tom McCarthy

(British; 16/1 Ladbrokes odds)

Satin Island may be an underdog for bettors, but Flipsnack, which built an algorithm to predict the winner of the Man Booker Prize based on the author’s nationality, the gender of its protagonist, its setting, and a wealth of other factors, believes it will be the winner. (Flipsnack's Man Booker Prize prediction app is a fun and informative way to wile away 15 minutes.) Writing in the New Republic, David Marcus described Satin Island as a “novel that follows a “corporate ethnographer” as he drifts from one North Atlantic capital to the next in the hope that he will find something to anchor him to our “negative world,” it is also a work of fiction that captures the ways in which we stubbornly still try to give the world’s absences meaning.” Satin Island is an outstanding novel, but it would be a decidedly more avant-garde choice than what the Booker typically goes for (something on the higher end of the middlebrow spectrum); the fact that Satin Island is not as obviously ambitious as two of its predecessors, Remainder and C, may also hurt the novel’s chances.