Political circumstances couldn’t be much worse for Canada’s prime minister, Stephen Harper, who faces a competitive election in October. Not only has Canada entered a recession, but Harper’s prize ally—the tar sands industry—has suffered a string of setbacks. Low oil prices have suppressed industry profits, President Barack Obama’s rumored to reject the Keystone XL pipeline any day now, and a socialist party won a recent election in Alberta (the oil capital of Canada). Nor does it help Harper that he's turned his country into a petrostate that's become the world's leading antagonist on climate action.

All of these factors have helped Harper’s more progressive opponents make unexpected headway. On paper, his opponents—Tom Mulcair of the socialist New Democratic Party (NDP) and Justin Trudeau of the center-left Liberals—look more aggressive on clean energy and the environment. But even if one of them wins, Canada's climate stance probably won't change dramatically. The oil industry simply has too strong a hold on the country.

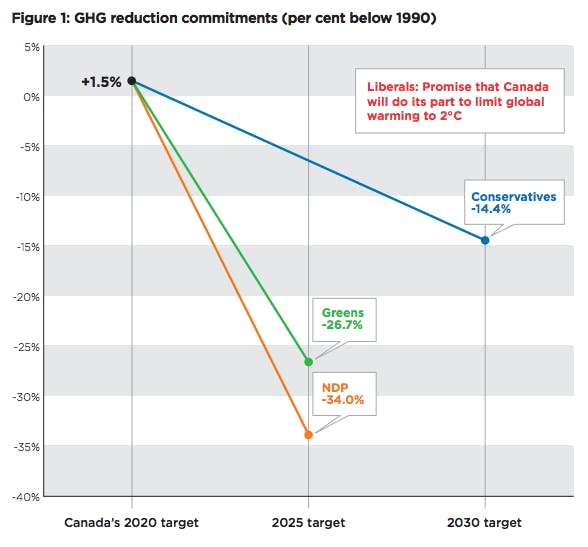

The NDP has put forward the most aggressive goals for greenhouse gas emissions, proposing a cap-and-trade system to get to 34 percent lower emissions by 2025. Liberals, meanwhile, have been short on detail. While Trudeau has insisted on doing something about Canada’s growing carbon footprint, and says Canada should do its part to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, he hasn’t proposed a policy or target. One thing Trudeau and Mulcair have in common is they both have called for a new approach to review pipeline applications in order to better account for their environmental impact. Harper, meanwhile, has proposed a target to cut carbon emissions by 14 percent by 2030, or 6.5 percent by 2025. Yet Canada has missed earlier targets under Harper and is now on track to miss its 2020 goal (as opposed to the U.S., which made a similar commitment and is on track for success).

In many ways, though, all three parties are still trying to compete to be the energy industry’s best friend.

In August, NDP Toronto candidate Linda McQuaig acknowledged something that’s probably obvious to observers: To meet climate goals, “a lot of the oil-sands oil may have to stay in the ground,” she said. That's in line with scientists' warnings about tar sands crude, which require roughly 17 percent more emissions to produce than other oil. But in Canada's political scene, McQuaig's statement was considered a gaffe. Mulcair quickly distanced himself from McQuaig, insisting her statement was not representative of the party’s official platform. “It’s possible” to both develop tar sands and cut greenhouse gas emissions, he said days later. “You have to put in place that sustainable development legislation and enforce it.”

NDP is moving to the center in order to compete with Harper. And Mulcair wants to show he can support pipeline projects, so he's called the Energy East pipeline—a bigger project than Keystone that would carry crude oil from the Alberta tar sands to the east coast—a “win, win, win.”

The Liberals have offered a few policy ideas on climate change, like ending fossil fuel subsidies and putting a price on carbon, but they've failed to deliver more details on what their emissions targets would look like. Meanwhile, they have slammed Harper for harming tar sands development. The Liberals have utterly failed to propose any details of their plans. Trudeau said in the first debate, “Mr. Harper has turned the oil sands into a scapegoat around the world for climate change and he’s put a big target on our oil sands.”

Environmentalists in Canada see a contradiction in how politicians discuss development: They say it’s impossible to ignore tar sands development while also tackling greenhouse gas emissions. While green groups admit it isn’t feasible to cut off oil production tomorrow, they want to see a plan for eventually getting there. It’s just not clear whether candidates will risk the political capital to do so.

“No matter what party is power, Canada is historically a country that exploits its resources,” said Daniel MacFarlane, a Canadian environmental historian who studies water policy.

And voters seem to overestimate the importance of the oil sands: A poll commissioned by Environmental Defence found that a majority of Canadians (57 percent) overestimate the role the tar sands play in the economy (2 percent of GDP). Environmental Defence's Clean Economy Program Director Keith Brooks said that he sees voters “having a good conversation in Canada about what kind of country we want to be: Do we want to be a good partner in collaborative talks or do we want to be betting on fossil fuels?”

Correction: A previous version of this story said Harper is Canada's longest-serving prime minister. He is the 6th-longest serving prime minister. William Lyon Mackenzie King was the first, serving 22 years nonconsecutively between 1921 and 1948.