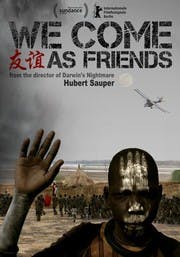

Arriving unannounced to South Sudan in a homemade flying machine to film a documentary, Austrian director Hubert Sauper parallels fictional space conquests and real colonial invasions. “I come in a vulnerable situation and I get out of a ridiculous flying machine. They laugh at me,” Sauper told me. “The connection that’s created in a relatively short time because of the oddness of our arrival is then our basis for conversation.” The resulting intimacy gives the film, We Come As Friends, an emotional core, which didn’t go unrecognized: It won awards at both the Sundance and Berlin International Film Festival.

That title, of course, refers to the stereotypical moment of first contact with intelligent life. But it also suggests the film’s preoccupation with the stories we use to make sense of our own foreign interactions. “We come as friends” is a hollowed out B-movie trope, and throughout the film, Sauper subtly exposes the other stories, often equally hollow, that we use to explain away our own interactions with developing African nations.

The film meanders, essayistic, from Chinese oil fields to UN bureaucracy, letting the camera’s gaze settle on white bodies handing out solar-powered bibles or lounging around hotel pools. In his flying machine, Sauper too becomes a structural device, his journey a backbone for the film’s interconnected subjects—globalization, Chinese-African relations, government corruption, displaced communities.

We Come As Friends begins at a hopeful moment, just before South Sudan’s referendum for independence in the summer of 2011. There’s a mood that, after years of colonization, the region will finally have its freedom. But in a matter of months, it’s back to business as usual: government corruption, war with north Sudan, and foreigners eager to make a profit in the name of progress. “From slavery to colonization to globalization, you have three waves of the humiliation of Africa,” Sauper tells me. “The interesting thing is that after all of this humiliation and racism and disgrace, we as Europeans, or Westerners, are still able to come up with a narrative that makes us the Savior.” Rather than just showing the consequences of interaction, Sauper’s film is powerful in the ways it depicts the psychology that allows these exploitative relationships to persist.

But what Sauper will say explicitly in our interview, he suggests much more subtly in the film. In one scene, a pale bureaucrat is giving a speech about bringing light at a ceremony marking the opening of an electric plant. It’s the details that drive these scenes: The feedback on the PA system during the speech, for example, undermines the ideal of technological progress he’s espousing. And afterward, when a local group perform a tribal dance in traditional dress with Western brassieres, it’s difficult to ignore the colonial desire to “civilize” the Other. While Sauper avoids providing commentary and allows these details speak for themselves, we often hear his voice behind the camera as he asks everyone he interviews to explain Africa, explain colonialism, explain South Sudan. It’s a simple method, but there’s a friction between the different stories that reveals how ideology functions. “Each one of us including and I [sic] are inventing narratives around our lives and our actions that make us emerge kind of okay,” explains Sauper. “Civilizations do that also.”

Sauper often returns to South Sudan’s legacy of colonization. But he makes it clear that, in the resource-rich country, patterns of colonialism aren’t just a legacy. One village elder shows the contract he was swindled into signing. It details all the rights to forestry, mineral, and petrochemical extraction that now belong to a Texas firm. We see maps of regions where these processes are well underway and others where initial surveying is beginning.

Sauper spotlights diverse voices: Chinese oil field workers, Texan missionaries, UN peacekeepers, and warlords turned politicians, as well as the most disenfranchised, like the whole communities forced off their land by development projects and students discriminated against for their traditional dress. In scenes of soldiers and schoolchildren alike doing drills, their bodies conforming to structured rows and rhythms, or missionaries forcing white athletic socks on a crying baby in a village, Sauper allows the country’s organizing principles to reveal themselves. Banal moments overwhelm dramatic ones. Details like a drunken peacekeeper threatening to beat Sauper up if he mistakes him for English instead of Scottish, or a warlord-turned-politician mumbling along to the national anthem to which he clearly doesn’t know the words illustrate a cynical portrait of South Sudan.

When I spoke with Sauper about the process of filming, his anecdotes highlighted the absurdity of those same principles—which are conspicuous in a place like South Sudan, where a particular bureaucratic weirdness rubs up against a decidedly unbureaucratic lack of infrastructure. Because so much of South Sudan isn’t mapped, Sauper found many of the places where he filmed by scanning the landscape from the aerial view of his plane. Sauper actually discovered a historic colonial village because it had a different spatial organization than everything else around it. “Of all these villages that are scattered out in the middle of nowhere, there is nothing straight. There are no straight roads. There are no straight lines because they are African villages,” explains Sauper. But “suddenly I saw an alley of trees in a line.” His hunch was right.

Uniforms are a product of the same type of thinking as planting trees in straight lines, and Sauper quickly learned that, to be trusted by uniformed people, he only had to wear one himself. After facing hostility from governments and militaries when landing unexpectedly and coming out the airplane in only a T-shirt, Sauper adapted. He and his co-pilot began to dress like airline captains. “With four stars on our shoulders suddenly we were a part of protocol and they were saluting us instead of arresting us, just for this stupid shirt,” says Sauper, “which is kind of mad!”

In the end, bureaucracy—that neocolonialist tool of oppression—rules and plagues both Sauper and South Sudan. “Bureaucracy is a tool for organizing societies,” Sauper says, and he includes many banal moments in the film: UN officials giving speeches and PowerPoint presentations and showing off scale models. “The UN,” Sauper explains, “is the quintessence of global bureaucracy. Creating power structures always helps the powerful and not the weak.”

And, according to him, savior narratives are intertwined in these organizational systems. “The UN is kind of reassuring us in the West that they are going to sort us out of chaos,” Sauper says. We Come As Friends counters one of these persistent narratives, that nations like South Sudan’s chaos stems from a lack of order, suggesting instead that the chaos for many South Sudanese today is a product of a very clear order, one that just prioritizes resource extraction, in the name of progress, over certain people’s lives.