I recently took a 24-hour, two-flight journey from Hong Kong to New York City. During that time, I consumed many of the culinary delights modern air travel has to offer: an aluminum tray of reheated pasta, a packet of unrefrigerated “pasteurized cheese spread,” a compressed bar of nuts and berries and grains, a plastic packet of chewy cookies, a bag of cheese-flavored crackers. These are not items you’d typically find in my kitchen at home, where I try to lean away from such processed foods. But when you’ve been wedged in economy for 10 hours and you’ve already run through an entire season of "Wolf Hall," Goldfish don’t just seem tempting, they seem downright necessary (see also: Xanax, bourbon).

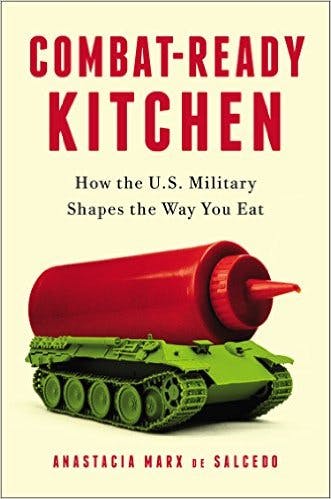

In her new book, Combat-Ready Kitchen, food writer Anastacia Marx de Salcedo finds herself in an extreme version of a processed-food feast, eating a two-year-old hamburger at an army research center. It isn’t rotten or moldy; in fact, it looks and smells fine (while the taste, she admits, leaves something to be desired). The shelf-stable burger—shelf-stable meaning it doesn’t need to be refrigerated—is of interest to the army as a reliable hit of calories to warfighters, as they are known: those serving in combat zones.

It is of interest to Salcedo, however, due to the qualities it shares with the pillowy slices of extended shelf-life whole wheat bread on which she herself lovingly layers deli meats each morning. Salcedo began to explore the connection between the military and the American diet when she was researching a series of articles about children’s lunchboxes, seeing its hand in the aforementioned industrial bread and those reconstituted deli meats. For all the inveighing against processed food, such items are increasingly omnipresent in the American diet; 61 percent of U.S. caloric intake, according to a recent report. And much of this food is produced using technologies that started—like our burger—with the military.

At the Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, a laboratory outside of Boston, Salcedo delves into the military research operations that have motivated the science of food and food preparation over the last century and that have, in the process, shifted consumer expectations of what food is and how it is eaten. She is most interested not in the “gee-whiz” funhouse of newly developed Frankenfoods, however, but in how army research translates into the commercial market, as large companies—ConAgra, General Mills, Frito-Lay/PepsiCo, all the usual suspects—queue up to work with the government on making these experimental products a mass-market reality. Alongside the burger, the combat meal she taste tests includes Combos—a packet of processed cheese-filled cracker rolls that can be bought in any grocery store.

The development of a military foodstuff is a lengthy process, but once achieved, it can enter the commercial market very quickly. Consider the energy bar: In the 1890s, the military attempted to make use of a portable indigenous North American mixture called pemmican—minced meat and corn mixed with animal fat—which was so unpalatable it left soldiers begging camping parties for food. By World War I, it was thought that chocolate could serve as a good, high-energy substitute. But the military required a bar that was not too sweet—if tasted too good, soldiers would eat supplies too quickly—and that wouldn’t melt too easily.

As with most developments in processed food, World War II was a breakthrough. In 1937, Colonel Paul Logan, the head of the Subsistence School at the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, began looking for a company “foolhardy enough to take on stripping the pleasure from one of humankind’s most seductive foods.” The company he found was Hershey. “Now the nation’s largest chocolate factory,” Hershey “jumped at the opportunity—being part of the rations supply chain would mean its sugar-gluttonous manufacturing line would never be subject to wartime restrictions again [as they had during World War I].” The resulting Logan bar, better known as the D ration, was a huge success. It was pressed into service during every U.S. military engagement until the Gulf War. The combination of protein, grains, and chocolate would be recognized in more palatable forms by consumers reaching for a Luna Bar today.

The development of such foods was vital during World War II, when the army suddenly had an unprecedented number of troops to feed. The Quartermasters Corps, which is tasked with feeding the U.S. armed forces, went from providing three meals per day for 400,000 troops to nearly 12 million. This was, as Salcedo dubs it, the “Big Bang” of the universe of processed foods. Thus began the hunt for extended-life bread, preserved meat that didn’t make people retch, and packaging that could be both light and durable. After struggling to feed the frontlines during the war, the Department of Defense was determined to be better prepared in the future. At the same time, luminaries of the military’s wartime processed food program moved into the private sector.

Since 1980, the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act has made transferring military research on food science to the private sector a central mandate rather than a byproduct of work done at the Natick Center, allowing a thousand foodstuffs to bloom. These partnerships develop under the usual flood of bureaucratic acronyms: Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAS) and the Orwellianly vague Other Transactions. “When companies work with the army’s subsistence department,” Salcedo explains, “they get the chance to dominate the market when new products based on it come shooting out of the pipeline,” either because they are granted “an exclusive patent or a head start on a breakthrough processing or packaging technology.” And the military, in turn, is assured of being able to mobilize and feed a large number of troops in an emergency. Should the need arise, the power of the U.S. processed food industry could be set to feeding an army.

A look into the food world’s DARPA is tantalizing, but, in Salcedo’s telling, it often becomes buried in lackluster histories and tedious scientific descriptions. Although at times Salcedo succinctly sums up the scientific intricacies of, say, Saran wrap, she more often gets bogged down in details that are neither illuminating nor totally comprehensible to the casual reader. Yet her book draws attention to some of the dangers of embracing convenient technologies without a full view of their long-term implications. Of plastic packaging, she writes: “A diet loaded with plasticizers may be an acceptable risk for soldiers, for whom the ability to throw a squishy package into a bursting backpack and tear into it on a moment’s notice is a true advantage, but maybe not for the rest of us.”

The same could be said for any number of these products. Soldiers churn through thousands of calories each day while on combat duty and often lose weight despite being plied with even more caloric replacement. The same cannot be said of the typical American, who instead needs anything but the calorie-dense, flavor-enhanced, salt and sugar preserved foodstuffs that work so well on the field of battle. The military’s quest to develop a stable cheese helped to make (somewhat) palatable the Meals, Ready to Eat consumed by soldiers; it also provided the American public with Cheetos.

Why, then, do we eat like soldiers? Salcedo’s chapter on processed meat products contains some of the book’s most interesting insights. She delves briefly into the McRib, looking at its fall and rise before investigating its patrimony. The McRib is an amalgam of restructured protein bits that many find distasteful, reliant as it is on unsavory factors such as bacterial enzymes, meat glue, and other food-like ingredients. Yet, the McRib makes use of all the part of the animal that Americans typically don’t want to eat in their unprocessed form: tripe, heart, and scalded stomachs. At a time when meat consumption is rising to unsustainable levels, the McRib answers an economic need. It even comes on and off the menu in relation to the national supply of pork trimmings. In 1966, the Advisory Board on Military Personnel Supplies’ subcommittee on meat products declared “the future of fabricated modules of meat [is] excellent and that studies in this area should be continued.” At one time, Americans hesitated to eat boneless meat; today, despite blowback against “pink slime” and other unpalatable meat slurries, it would seem that taboo has largely been broken.

The power of Natick to shape food science, and therefore consumption, “comes not from the size of Natick’s research budget, which is relatively small, but from the simple fact of having an overarching goal, a long-term plan, and relentless focus,” Salcedo writes. The research that the Natick Center undertakes to feed women and men in combat is vital, lifesaving work. However, as the prevalence of both hunger and obesity shows, the current reliance on food science to provide solutions through processed food is foolhardy. Let us hope that the movement for sustainable food finds its own overarching goal, a long-term plan, and relentless focus sooner rather than later. In the meantime, enjoy the McRibs.