Nael Marcus Nissan sat smoking with his legs spread on a burgundy couch in an abandoned home in the village of Baqofa, 15 miles from the Islamic State front lines. Nissan was a fighter with the Dwekh Nawsha, one of the three primary Assyrian Christian militias founded in the Nineveh Plains in northwest Iraq’s Kurdistan, in the months after the ISIS invasion in June 2014. The Dwekh patrolled Baqofa in a black pickup truck with a small crucifix scratched on its side and a Russian machine gun mounted in the bed. They spoke Aramaic, the ancient language of Christ. Nissan was 25 years old, with high cheekbones and a trimmed goatee. He wore aviator sunglasses, a floppy camouflage hat, baggy fatigues, and an ammunition vest stocked with grenades and cigarettes. He preached gospel at the evangelical church in Dohuk, and since he learned English from listening to ’90s-era rap, he quoted Scripture in the cadence of Ja Rule. “I’m from New York,” he sang. “No, I’m from Baghdad!” His favorite song was Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise.”

“Did you see the guy like Robin Hood on our flag?” he said. It was tacked on the wall alongside paintings of Jesus with his heart lit up like a bulb. The flag was a white field with a golden orb surrounded by a four-pointed star—the sun—at its center. Red, white, and blue stripes stretched to each corner, representing the Tigris, Euphrates, and Great Zab rivers. At the top was Assur, the archer, “the god of empire and the god of war,” Nissan said. “God punished the Assyrian Empire. Now he punish us for the many sins we do.”

Nissan lit another cigarette. He wore gold rings on his pinkie fingers and had “John 3:16” written on his ammunition vest in black sharpie. “We fight to prove our existence,” he said. “The Assyrians have lived on this land for 7,000 years. If we lose the language, we lose the Assyrian people. We’ll disappear.”

Baqofa was empty other than the fighters. An elderly deacon named Yusef Odisho, along with Nissan and the rest of the Dwekh fighters, took me to a high-walled courtyard that enclosed an ancient Christian graveyard and a church constructed nearly 400 years ago. The graveyard was covered in dust and overrun with weeds. “This is my father,” Odisho said, reading the inscription on one of the headstones. “This is my grandfather.”

The doorway to the village church was blocked by an empty coffin. A short bearish soldier kicked it aside. The walls were an oceanic blue and there were six rows of wooden pews. A plastic Christmas tree lay on its side near the altar. Someone had filled a whiskey bottle with wine used as the Blood of Christ. Dog feces covered the floor of the room in which the children took Sunday school.

“Did Santa come?” I asked.

“With bombs, guns, and suicide,” Nissan said.

“This is not the first time we’ve been so close to disaster,” Odisho said. “This is always happening, and Iraq is always divided. This is the land of all religions. The land of ruins.”

In the nuns’ quarters, someone had left behind a letter to the looters:

Brothers,

We forgive you for your foul deeds. You have robbed our convent. Do you not know that we are virgins? We have no one to support us with money. You even put the refrigerator at the door to steal it at night. [You stole] the blankets, mattresses, gas canisters, and even our clothes. How can you say that you love God while you steal the livelihood of the poor? God does not have mercy on robbers. Unlawful deeds bring calamities upon their doers.

Your mother,

The Nun

Among the rubble Nissan discovered a ruler with each centimeter marked by the head of an American president. “George Bush destroyed my country and Barack Obama brought ISIS to my country,” he said. “All of them are Illuminati.” Nissan was fascinated by Illuminati. He owned three or four books on the subject. Later, when I got to know him better, he turned to me and said, “Suddenly I feel you are Illuminati.”

The Assyrians are the indigenous people of Iraq, native to the Nineveh Plains, home to some of the oldest continuous Christian communities in the world. Christianity arrived in Nineveh in the first century, hundreds of years before Muhammad was born and Islam came to Iraq. The earliest known historical records of Baqofa date to the seventh century. Some believe the Yazidis, who practice a syncretic Middle Eastern religion that blends elements of Zoroastrian and other ancient Mesopotamian faiths, are descendants of the Assyrians who sought refuge in another faith after the fall of their empire.

Timeline: Conflict in the Nineveh Plains

ISIS entered Nineveh Province in June. Mosul fell in three days, and the militants moved east, past the ruins of the ancient city of Nineveh, into the heart of Iraq’s Christian community. They took the village of Zumar, and then Sinjar, where as many as 1,000 Yazidi men there and in nearby hiding places kneeled and died by firing squad before their corpses were bulldozed into mass graves. In Qaraqaosh, the largest Christian city in Iraq, 1,500 died by sword. They chopped a five-year-old in two.

It was evening when the nuns of Baqofa—Sisters Katrina, Magdalene, Noor, and Mary Dominique—heard shouting in the streets. ISIS was coming. They had ten minutes to flee. If they didn’t, the militants would do to them what they had done to the Yazidis: Sell them or behead them. The nuns fled before the assault, in a yellow school bus, until they reached the neighboring village of Telskuf. They watched news of the ISIS advance on television until a fighter from the peshmerga, the military force that controls Iraqi Kurdistan, told them to leave. Sister Mary Dominique, the eldest nun, stood up. “A Muslim is telling us this. It must be serious,” she said. They headed north, to the city of Dohuk, driving slowly because there were so many families fleeing on the road. Sister Mary Dominique wept the whole way. When they arrived at Dohuk, the monastery was already full of Christians. They drove as far as they could into the mountains and lived for weeks in an abandoned village. It was as far as they could get from everything.

The peshmerga drove ISIS from Baqofa in late August. They occupied the village for three months, looted it, and blamed ISIS for what they’d done, carrying away refrigerators, air conditioners, televisions, anything of value. They said the village was not safe, that ISIS could return, and they graffitied the doors to the homes and shops: no one is allowed in here. Do not enter here. They tore the pages from holy books and scattered the pages like leaves. Now, the Dwekh were in control.

The Dwekh had set up base in a house that once belonged to the village mayor who had fled and was now living in a caravan near Dohuk. The house, still full of photographs of the family’s children, was enclosed by a mud wall covered in scribbles of bunnies, humans with mechanical body parts, a veined eyeball. The heads of rose-colored thistles grew above the wall.

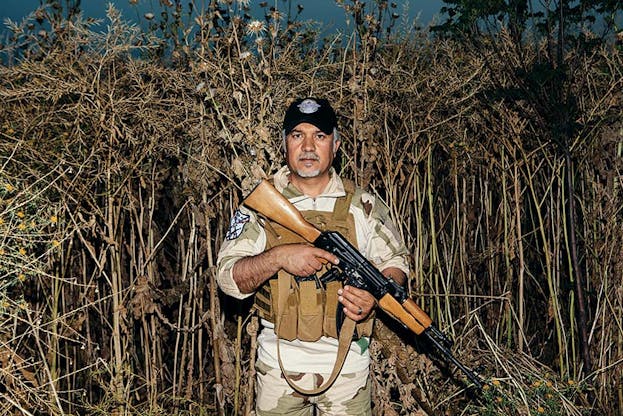

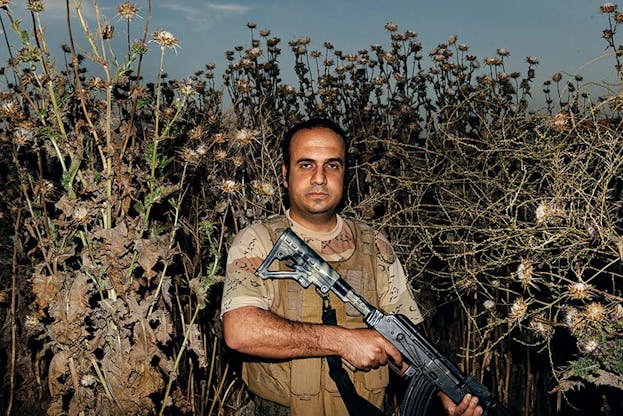

The days were quiet and they had little to do. There were no marching drills or arms training, and there were no formal patrols set. They eavesdropped on ISIS radio chatter and listened as their enemies complained about the lack of women. Most of the fighting was between ISIS and the peshmerga elsewhere in the region, but ISIS lobbed shells at them periodically. The men passed the time watching movies: The Passion of the Christ with Mel Gibson or Tears of the Sun with Bruce Willis. They liked professional wrestling and would gather to watch WWE broadcasts. They posed for pictures with their weapons and posted the shots on Facebook. They drank tea and smoked cigarettes. In the afternoons they prayed.

In a sandbag bunker on the roof of the mayor’s house was a telescope. They kept it trained on the black flag of the Islamic State, which flew over the nearby Christian town of Bartella. Many of the Dwekh fighters were from Bartella, and in the evening they climbed onto the roof and watched their homes light up in the dark.

Nineveh was full of dead cities and oil fires. A sickly yellow fog hovered over the flat plains. On the way to Baqofa I could see smoke rising from Mosul. Within Nineveh’s borders are the overlapping lives and beliefs of the Turkmen, Yazidis, Shabaks, Sunni and Shiite Arabs, Mandeans, and Assyrian Christians. The soil of the Assyrian Empire, which once stretched from Egypt to Persia, is buried beneath the soil of Kurdistan. In its eastern sector is Lalish, the center of what the Yazidis believe is the historical location of the Garden of Eden, which once nurtured the Tree of Life and led to the fall of man.

The region is not barren of biblical romance. There are the sites of old biblical stories, and ruins that are symbols of eternity. Nineveh demands our mythologies because it supports them.

ISIS has targeted the Yazidis, Assyrian Christians, and the region’s other minority groups for persecution. Each faith is fighting over the same questions they were fighting over when their theologies developed, which is really the question of which culture will be dominant, whose God, or whose version of God, will be the better God. This fight has meaning not only here but around the world, and its battlegrounds inexorably draw the faithful to its violence.

The American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan advanced a simplistic concept of good and evil, a dichotomy that continues to exist in the minds of those who dictate our actions abroad. “We carried our grief to the Lord Almighty in prayer,” said George W. Bush after September 11—and we took that grief and that God with us in search of hegemony and revenge. And if it is true that the failure of American imperial ambition in Iraq created the conditions that led to the rise of ISIS, then, too, ISIS’s existence provides an opportunity for redemption. “We’re not going to let them create some caliphate through Syria and Iraq,” President Obama said in August 2014, as he used ISIS’s atrocities as a reason to renew air strikes in Iraq and continue the military operations he vowed to end. Obama, it could be argued, was not interested in a theocratic campaign against ISIS—his concern was preventing genocide. But ISIS’s actions tapped into the public’s lingering Bush-era mentality in a powerful way. In Congress, meanwhile, calls went out to support the peshmerga. Five hundred million dollars in U.S. aid was proposed as the amount necessary to protect the weak and vanquish the villain. Rand Paul, in an outpouring of Western largesse and presidential enterprise, went further, suggesting the Kurds be granted their independence from Iraq, saying, “they would fight like hell,” if freedom was the reward for ISIS’s demise.

Together, the Assyrian Christian militias have an estimated 500 to 900 men under arms. The Nineveh Plains Protection Unit (NPU) is based largely in Dohuk. Its web site calls for the development of a “native defence force” to “safeguard existing Assyrian and Yazidi lands and take back what has been plundered.” For a donation of $100 or more, supporters receive an “archival quality” photo of an NPU fighter, smiling and bearded, holding a weapon, his shoulders draped in ammunition bandoleers. “These prints will last for years, and can be hung as a poster or framed and placed in your home.” The Nineveh Plains Forces (NPF), based in Telskuf, operates under the auspices of the peshmerga, which provides them with weapons and training, obviating the need for a comparable online fund-raising apparatus.

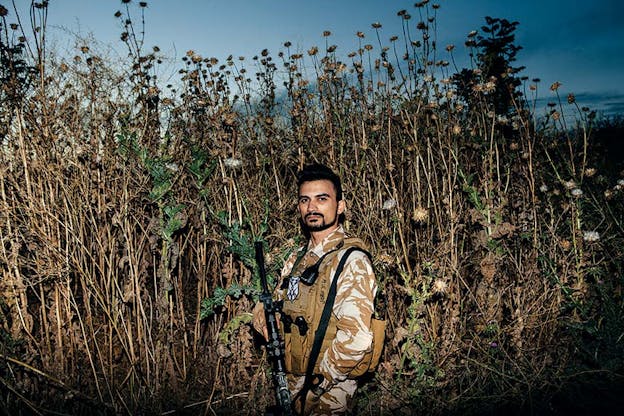

The Dwekh is the only militia that welcomes foreign recruits. Rama Baito, the Dwekh’s digital media manager, told CNN in April that the group had a waiting list of 200 foreign fighters looking to join. “We simply do not have enough weapons or training capacities,” he said. The first American in the Dwekh was a 28-year-old from Troy, Michigan, named Brett Felton. Felton’s Facebook page lists the Dwekh and Jesus Christ as his employers. His cover photo shows a thin and handsome young man with mournful brown eyes and a well-tended mustache. He is seated on a couch in a Dwekh camp, in full fatigues and sunglasses, a kaffiyeh wrapped around his neck, holding an assault rifle. A large cross is overlaid on the image. In another photo, Felton is shown again dressed in fatigues, his kaffiyeh this time wrapped around his head, wearing body armor with an American flag and an Iraqi flag sewn on (the U.S. flag on top). Six other foreign fighters had been with the Dwekh, until June, when, according to Albert Kiso, the militia’s spokesperson—a different role than digital media manager—they got bored and took off with the peshmerga to a base near Sinjar. “They wanted to have fun,” Kiso said.

Felton arrived in Baqofa in August 2014, the phrase “King of Nineveh” written in Arabic across his ammunition vest. On his right forearm was a tattoo of Jesus and on the left a machine gun. On his back was the archangel Michael. Felton’s presence brought a great deal of press and social media attention to the Dwekh, which helped with donations. He set up a PayPal account for people who wanted to contribute, using the email address soldierofchrist2005@gmail.com. In news reports, he identified himself as a “crusader” and said that it would be “an honor to give my life” to protect Christians from ISIS. He added that he had come to Iraq to “keep the church bells ringing.”

No one knows how many Americans have journeyed to Iraq to fight ISIS under the guise of Christian idealism. “We patrolled every day, got shot at, mortared, hit by IEDs [Improvised Explosive Devices], one of my friends was killed,” Patrick Maxwell, a former Marine sergeant who returned to Iraq in 2014 and fought with the peshmerga, told The New York Times. “But I never saw the enemy, never fired a shot.”

Still, for the Dwekh, the presence of Christian crusaders, from America or elsewhere, is not a welcome one. Although they are an independent force, they work closely with the much larger and better-armed peshmerga, who are predominantly Sunni Muslims. Nor was there much affection for Felton, who left the Dwekh in March. Before he left, Nissan told Felton, “Your God is not my God. Your God is a businessman.” One day when he was still in camp, Felton drank too much whiskey and passed out. Nissan opened his laptop. It was full of photographs of naked women.

“King of Nineveh,” Nissan said of Felton. “What an asshole.”

Outside the city of Tal Afar, which sits in the Nineveh Plains northwest of Mosul, a range of low green hills marks the border between ISIS and Iraqi forces. The peshmerga have small bases located every few miles along the front line. Tal Afar, which is under ISIS control, is situated just on the other side of the hills in a low desert plain. To the west is Mount Sinjar, where Kurdish forces and ISIS regularly exchange fire. The roads in the area are cracked with craters from explosions. The day I arrived ten ISIS militants were arrested in a nearby village. Weeks earlier, villagers had come upon the corpses of several ISIS fighters being eaten by dogs.

Colonel Khaled Hamzo and his soldiers occupied a peshmerga base near the front. They were billeted in an abandoned home a couple of miles away. It was a two-story stucco structure, comfortable, with a balcony and a garden filled with pink flowers. The foreign fighters were in the garden in their fatigues and body armor, carrying their weapons. Between them was a table crowded with cigarettes and Tiger brand energy drinks. The lawn in the garden was immaculate with pink flowers in full bloom. Fields of deep grass stretched for miles in every direction. They’d been in camp with Colonel Hamzo for a week.

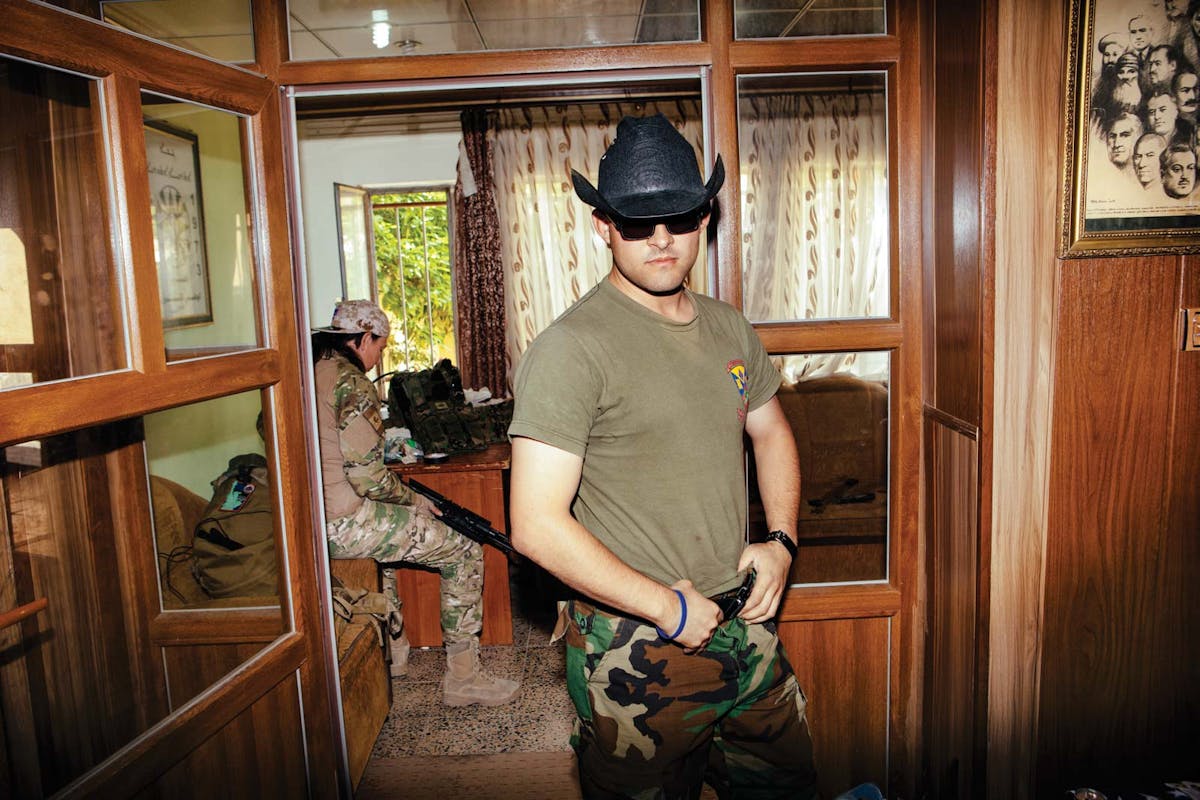

“I’m representing the Marine Corps,” said Louis “Tex” Park, a 25-year-old from Houston. “This is the kind of shit we do when we get out.”

Park had been discharged from the Marines in January 2015 due to problems he had after he was diagnosed with PTSD. He had served in the infantry in Afghanistan. Things didn’t work for him after he got home, Park said. All he did was drink. He broke up with his girlfriend, found another, broke up with her. Therapy helped, and when things finally got better, he saved all his money to buy a first-class airplane ticket to return to Iraq. His family wasn’t happy about the decision. They told him they didn’t think killing ISIS was a very Christian thing to do. “If doing the right thing earns me a place in hell,” Park said. “Then I’ll take my rightful place in hell.”

Later, Park said, “A lot of Western media out here think we are doing a lot of fighting.”

“What have you been doing?” I asked.

“This sort of thing,” he answered. He meant sitting and waiting and talking to reporters.

Richard Jones, 29, had a trim auburn beard, intense eyes, and a slightly cross-jawed underbite. He wore Oakley sunglasses with a rainbow sheen. He had done two tours of duty, one for the U.S. National Guard in 2004, and another for the Georgia State Defense Force in 2010, but he had never deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Jones was one of the newest recruits to the Dwekh Nawsha.

Cory was a 24-year-old U.S. Army veteran who’d served a tour of duty in Iraq. (He refused to tell me his full name.) The Dwekh had called him “Hot Pussy” because they thought his long hair was girlish. He had been in the country only two weeks, traveling here to make a documentary about the Western fighters taking on ISIS. He had abandoned the project when he couldn’t find anyone fighting. “I thought there was going to be this big push, this big front,” he said. “But there wasn’t a big push or a big front.”

Cory and Jones had GoPro cameras (corporate slogan: “Be a Hero”) attached to their ammunition vests.

Jenny wore fatigues covered in Canadian flag patches. She said she had a military background but was reluctant to describe it in detail. “I think the media already made up a story about me,” she said. “I’ll roll with that.”

“Jenny” was in fact Gill Rosenberg, a 31-year old Canadian-Israeli originally from Vancouver. In 2006, she had immigrated to Israel, served with the Israeli Defense Forces, and then gotten involved in a telemarketing scheme that scammed thousands of dollars from senior citizens in the United States after telling them they had won the lottery. She was extradited, pled guilty in a Manhattan court, and served a couple of years of a four-year sentence. (Rosenberg did not reply to several requests for comment.) She received an early release predicated on the condition that she remain on U.S. or Israeli soil, but in 2014, she slipped out of the country and into Syria to fight ISIS, a move she described as “an act of redemption.” She left Syria in January to fight with the Dwekh and now the peshmerga.

There was one other Westerner who no one really talked to because his British accent was so thick it wasn’t worth the effort. He looked worn out, like a gnarled tree root. Everybody called him Jimbo.

“You seem like an expert,” I told him.

“Unfortunately not,” he said.

They’d received an influx of messages from foreigners interested in joining the Christian militia but they told everyone it was a waste of time and there was a lot of bureaucracy. They were, as far as they knew, the only group of Westerners in the area. The mission for these the Western fighters was simply to get a mission. Park was with the Dwekh for eight months and never fired a round in anger. He helped out tracking ISIS’s movements and did a little work training the fighters. And he spoke to members of the Western media, who were, of course, excited to know that adventurers from America had joined the fight. Colonel Hamzo treated them more as guests than soldiers. They ate large meals with him and slept on the floor of his bedroom alongside his top commanders. The rest of the soldiers ate less and slept wherever they could.

Colonel Hamzo and Mohammed Ahmed, his second in command, joined us in the garden. The colonel wore a brown jumpsuit and a wide belt. Ahmed spoke English with a slight British accent and wore a green vest over his uniform.

“You should ask them questions,” Jones whispered. “Because they always feel left out.”

“So tonight,” Ahmed said. “100 percent daesh attack.” (Daesh is a pejorative term for ISIS in Arabic.)

“Daesh is coming?” Park asked, kicking his legs and leaning forward. “After the battle we will count the bodies to see who killed more, you or me.”

“Winner buys chai,” Cory said.

“Fuck that,” Park said. “If we kill more daesh, we get to stay here.”

“Let’s go to Tal Afar,” Jones said.

Ahmed stared at the men. “Listen,” he said. “When you fight, you kill someone. Fighting isn’t a joke.”

The smiles disappeared. “We know,” Park said. “We’ve lost friends fighting.”

“Clearly we’re not going to go attack Tal Afar now,” Jones explained to me. “Sometimes you ask for the big trip even if you get the little trip. It’s just like a lot of times we wear our equipment and uniforms to reinforce the concept that we’re ready. I don’t want you to think we’re just sitting here making jokes. If you talk about invading Mosul, well, maybe they will let us go to Tal Afar. But we won’t go to Tal Afar. You know?”

“We are definitely not the A-team,” Cory said. “But it works for us.”

Nissan lived with his mother in a small house in Dohuk. I traveled there one afternoon on his day off. He was chain-smoking in the street, dressed in a white tank top and bleached jeans. He needed money, so we set off looking for an ATM. Sewage ran in the alleys. A cat trapped in a plastic bag struggled for breath. Without his camouflage hat and Kevlar, he was skinnier than I’d imagined him to be. His greased hair sparkled as if encased in ice. He invited me inside his home and showed me to his tiny room, where he had a bookshelf full of Bibles. He introduced me to his mother, who wandered around the house in a flower-print dress looking fretful. I asked about his father. “His heart exploded,” he said, adding after a beat, “From all the coffee.” Nissan had five brothers, but he was the only one who stayed at home to take care of his mother. She suffered from a psychiatric disorder that included symptoms associated with schizophrenia or perhaps depression, but Nissan had never been able to take her to a doctor to find out exactly what was wrong.

Before joining the Dwekh, Nissan had worked for a telemarketing company called CSS Global. He had never bothered to figure out what the CSS meant. “Doesn’t matter,” he said. “Just one shithole on the way to another.” He was raised in the Assyrian section of the Baghdad neighborhood of Dori. His whole life, he said, violence had trailed him. Packs of stray dogs used to chase him through the Baghdad streets. His mother beat him; his father, too. When the Americans arrived in 2003, Sunni extremists took over his neighborhood. He survived two IED strikes and three car bombs. One of them struck a Baghdad market where he was selling French perfume, so close by that it singed his hair and knocked him over. In 2006, the Sunnis commenced an ethnic-cleansing campaign in Dori. They stopped cars on the street, asked the religion of everyone inside, and shot the Christians. During these years, many of Nissan’s friends joined Sunni extremist groups and a couple threatened to kill him. He lost a friend to cross fire between the Americans and the extremists.

In 2007, his family fled Baghdad to Nineveh, where his grandparents lived. Under Saddam, Nineveh had been a refuge for Assyrian Christians, a place where they could live with relative autonomy and security. That changed after the regime fell and grew worse following the 2004 U.S. assault on Fallujah, which drove Sunni extremists north into Nineveh. The Assyrians, seen as allies of the Americans, became targets. “Leave or die” notes appeared on doorsteps.

Nissan took work as a shepherd in a village outside of Dohuk. He slept on the ground among his sheep. He didn’t shower and spoke to no one. After a year he came in from the fields and asked his father for a cigarette; they smoked, and he felt a surge of warmth stirring in his heart. That night he showered and lay in the living room where his family slept together by the air conditioner. He was Christian, and there were Bibles in the house, but he had never read them with much attention. But now he rose to find them. He opened one to Genesis and then to Isaiah. He read Psalms. He read John, Peter, Jacob, and Jehovah. In John, it talked about love.

He went to the bathroom and looked at himself in the mirror. “I’m no Christian,” he said. “All these years I thought I was a Christian, and now I find out I’m not a Christian.” He smoked, he drank, he made problems. He hadn’t been living his life according to Scripture. Then he heard God say, “Yes, you’re not Christian. You don’t love people.” It’s true, Nissan said to me. I didn’t even love my mother or my father.

The following morning he went to a service at a Chaldean Catholic church—the primary Iraqi Christian denomination—but nothing made sense. He tried to pray, and he felt something in his mind, something rising; he thought it was God, but it was only a headache. He left the Catholics for an evangelical church led by a priest from Detroit who spoke in tongues. The priest put his hand on Nissan’s shoulder and gave him three prophecies, and one of these prophecies was that he would be a leader of men; leading them not to war but to God. “I read the Bible more and more after that.”

In 2009, he was baptized, and he knew that when you go underwater, you die. And then you come out and you have a new life. Now his thoughts were interrupted by the babbling of God. He heard words, audible sounds. God had started the war in Syria, and it will never end. All of Damascus will be destroyed. Babylon will be destroyed. Nissan believed that the apocalypse is near. “God is out of time,” he said. “Daesh is the monster in Revelations.”

When ISIS was advancing in Nineveh, everyone fled to the mountains. Nissan didn’t run. He walked the deserted streets of Dohuk and listened to “epic music,” compositions that left him with feelings of grandeur and heroism.

“Daesh, they’re like ghosts,” he said. “The sound of daesh coming is the sound of the wind.”

The Jesus Loves Those With Broken Hearts Conference was held in Dohuk in mid-May at Geli Hall, a modern performance space with polished white floors and dangling purple lights. In its scale and aesthetic the hall was reminiscent of an American mega church. A Lebanese singer from Boston named Nizar Fares sang songs for the broken hearts of the displaced. He wore a powder blue blazer and white jeans. The conference was organized by a Sacred Heart priest named Sheikh Abu Rami, who ran a medium-sized but very popular church in the center of Dohuk. Dozens of priests and hundreds of displaced people—the broken hearts—were in attendance, some Christian, many not, and donations had been collected from as far away as Canada and the Netherlands.

Most of the displaced families lived in a construction site across the street from Geli Hall. They’d lost all their possessions and homes, and had been witness to firing squads, torture, abductions, and women sold into sexual slavery. A 28-year-old Yazidi from Sinjar who said his name was Amar told me about a family whose daughter had been tied to a chair and burned alive. In the back row, seated alone, was a young Yazidi man in a black suit. He hung his head and gripped a thick Bible. He was working as a teacher in a village of 400 people near Sinjar until ISIS arrived, killing all the boys and stealing all the girls.

“King Peacock,” he said, “never came.”

For the Yazidis, God is the creator of the world, and the world is under the care of seven holy beings, the chief being Melek Taus, or King Peacock. Thousands of years ago God sent King Peacock on a mission to visit earth and make it beautiful. He landed in Iraq and saw volcanoes, earthquakes, and other unpleasant things. Melek Taus fell from God’s favor and was exiled to hell. Unlike Satan, the fallen angel of Christendom, King Peacock extinguished the flames of hell with his own tears. He cried for 7,000 years, and God forgave him.

It was dusk and bats swooped the fields. The peshmerga bases glowed like bonfires along the front. The foreign fighters had climbed to the roof of the house to talk away from their peshmerga hosts.

“Scientists came up with this theory,” Jones said. “You can’t observe something without changing it.”

“Reality might change now,” Park agreed. “It’s like Schrödinger’s cat. You know we can’t ever see things for what they are because even to observe things changes them.”

Everyone agreed Park had gotten the name of the theory wrong, but no one knew which one was the right one.

“I’m talking about how you can’t see things in a pure way,” Jones said. “The fact is even when a journalist comes it’s almost impossible for them to actually see us. It’s almost like we are acting in an unnatural state.”

“That’s right. You being around changes things. This means we might not get to the front,” Cory said. “We’re out here, you’re out here. What the hell is everybody else doing? If the Holocaust had happened to the Jews in the time of Facebook, how many people would have sat back and let it happen? There is genocide going on. Why is it so hard to do good?”

“The naïveté,” Jones said, “comes from the belief that everything that happens in the world is happening on a television screen.”

“We are men of action,” Park said. “It hurts.”

Colonel Hamzo came up the stairs with a group of his soldiers and pointed flashlights in our eyes. One of the soldiers walked to the edge of the roof and searched the fields. The beam was thick and bright. Colonel Hamzo slipped his hands over Park’s shoulders. Choni, he said. Something was on the way. Two large armored vehicles on our side of the hills.

“What? Daesh is coming? This is great news,” Park said. “If it has wheels, we can shoot it. We can jack it.”

The colonel gave no commands.

At two in the morning, we were eating meat by a fire in the yard when Ahmed stopped by to announce that the militants were on their way. He wrapped a kaffiyeh around his head and tied a knot in the back so it hung down his neck like a ponytail.

“You look like Geronimo,” Cory said.

“We killed a big boss today,” Ahmed said.

The boss was Abu Alaa al-Afari, and he was second in command to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS. They had caught him at the Martyrs Mosque in a village outside Tal Afar. The peshmerga slipped ammunition vests packed tight with magazine rounds over their heads. They retrieved their weapons, and piled into three trucks. The foreign fighters joined them.

Colonel Hamzo removed his vest and put it on me. He handed me an AK-47, took my photo, and retrieved his rifle. Then we left. I rode with Colonel Hamzo and three others in the back of his Land Cruiser. We drove for ten minutes. The grass was deep and the road dark. The foreigners were in the truck ahead of us.

The driver turned on his low beams. Stray dogs loped in and out of the lights. What sounded like a chant broke the silence. The colonel turned up the volume on the radio. It was Kurdish propaganda music, a bolster for death and patriotism. “Peshmerga. Peshmerga. Peshmerga,” the voice said. A video screen lit up the center dashboard, showing images of soldiers eating meat or marching. Colonel Hamzo moved his hands to the music. He lit a cigarette and flicked the ashes at the dogs.

The base was nothing but a single makeshift bunker, a lean-to of sorts fashioned out of sandbags and old blankets. Soldiers crowded beneath a yolk-colored light. The air was cold. Beyond the edge of the base there was nothing but blackness, the abyss of the Islamic State. Park ran off to man a PKM machine gun. Jones handed me a glow stick. “Wave this around if you disappear,” he said. The shelter was rimmed with floodlights and the peshmerga outside stood casually illuminated. One of the trucks attempted to turn around but got stuck. It kicked dust, and the wheels groaned.

Colonel Hamzo walked calmly into the shelter and sat on a cot with his legs crossed. I followed him inside. Jones and Cory sat across from each other. Cory had brought along a PSL Romanian Sniper Rifle and Jones an AK-47 assault rifle. The two sat on the edge of the cots with the gun between their legs and ping-ponged military jargon.

Cory said he had first two and then every other. Jones asked Cory if it was a nine or a six. Cory said it was a one. Jones said let’s crank it six because a six is zero plus five plus four. Jones wished for z-mags. Cory wanted infrared laser. “If we hit the IR-7s on the sevens with laser, we’d go far,” Cory said. Jones guaranteed infrared in the green beam. Cory swapped mag rounds. He said he’d keep one molly if Jones racked it. Jones said look for the red magnesium tag on the rear. Cory said he felt good with that dope, hold low for close or high for far. He’d roll.

So many days without a mission, without fighting. It seemed to have built up a pressure inside them, and we were beginning to see it fissure.

“I can’t wait to get out there,” Jones said. “You are lucky you get to see this.”

Cory clicked a magazine into place and stood up. The peshmerga were all staring open-jawed or laying on their backs smoking. “I feel like I am the center of attention right now,” Cory said.

A moment passed. The colonel spoke with Ahmed. A few soldiers went in and out. “What are we waiting for?” I asked.

“Something to happen,” Cory said.

Colonel Hamzo pressed his hands together. “Let’s have chai,” the Colonel said. I leaned over to Cory who sat to my right. “Why are we drinking tea?”

“Fuck if I know,” he said.

The peshmerga smoked. Cory sat back down and I continued writing. Colonel Hamzo asked if I was done yet. He nodded towards my notebook, and I had the distinct feeling that this was a set up, the whole thing was staged; the foreigners equally towed in.

The colonel put extra sugar in my tea, and then he ordered everyone back into the vehicles, and we returned to the base.

Back in the colonel’s quarters the foreign fighters lounged on the floor and ate plates of fruit. “It’s time to sing,” Colonel Hamzo said. There was an awkward pause: No one volunteered.

“Every night,” Park said. “Not a day gone by we don’t work in Top Gun.” He pulled out his iPhone and nodded his head to “Highway to the Danger Zone.”

“Hey, Boss,” Cory said to the colonel. “I don’t remember you singing.”

Colonel Hamzo shook his head and swatted the air with his hands. No one would sleep until the Americans sang.

“OK,” Park said. “Guys?” He sighed. “Star-Spangled Banner?”

Park unpacked an American flag that he had brought with him to Iraq from Georgia. “Got to get out the flag,” he said. They all sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” but didn’t make it to the end. They didn’t know the words. So they tried a tune from Team America: World Police.

“America,” they sang. “Fuck Yeah!”

The photo of Louis Park originally incorrectly stated that he was at a peshemerga base near Tal Afar.