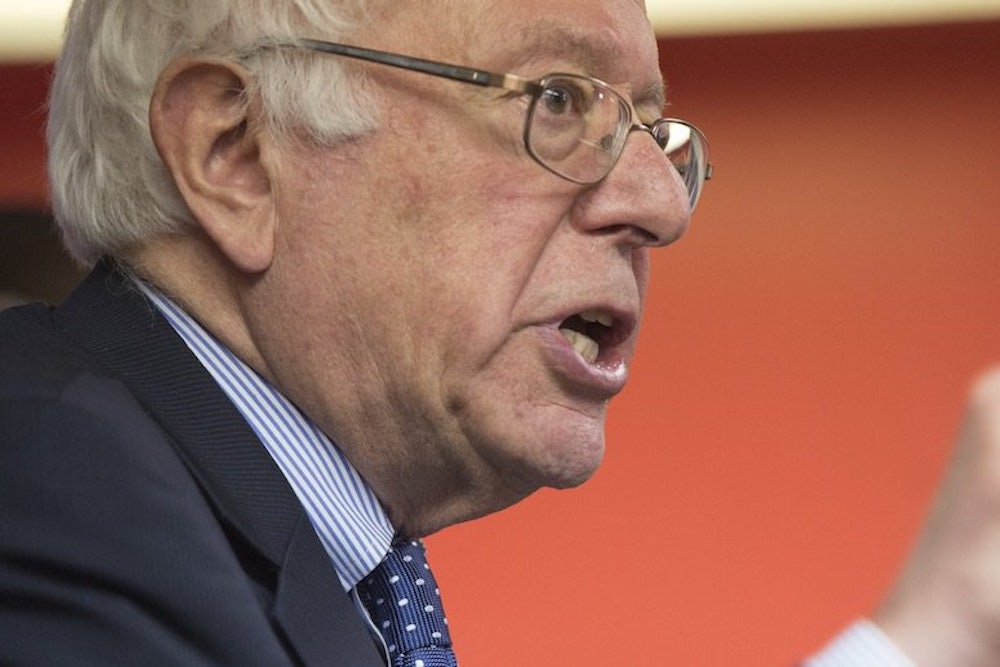

Bernie Sanders, the Democrats’ 2016 insurgent, has prided himself during his long political career for being relentlessly focused on the issues he’s cared about the most: corporate greed, economic exploitation, and inequality. However, the challenges that he’s faced from #BlackLivesMatter activists and questions surrounding his appeal to voters of color and his plans for addressing structural racism have forced Sanders to adapt his message. He’s now going out of his way to show his concern about race and criminal justice issues. But it’s still a bit awkward for him.

On Wednesday night, Sanders spoke in a digital broadcast to supporters gathered at more than 3,500 house parties across the country. He was introduced by an African-American woman who spoke of his record fighting mass incarceration and police brutality. Though he spent most of his brief remarks on economic issues, Sanders also condemned the way that police had treated Sandra Bland, a young African American woman arrested after a traffic stop and found dead in her Texas jail cell three days later. Then came the windup to his concluding call for unity.

“When we overcome race issues, when we overcome questions of whether somebody was born in this country or not, when we overcome sexual orientation or gender issues, when we don’t let our opponents divide us up by race or sexual orientation, all that stuff,” he said. “When we stand together, there is nothing, nothing, nothing, we can’t accomplish.”

He’s certainly trying. After facing shouting protesters at Netroots Nation two weeks ago, Sanders quickly stepped up to denounce Bland's treatment (“That happens all over this country, and it especially happens to people of color”) and connect his economic message to race (“Providing free tuition at public colleges and universities will be a huge step forward for this country and the African-American communities”). But in his brief remarks on Wednesday, his appeal to identity politics remains vague—in contrast with, say, his call for a $15 minimum wage—and he seemed disconnected from his core economic message. After describing what happened to Bland, Sanders remarked: “We’re seeing that all over this country.” He went so far as to describe “institutional racism” as the problem, without elaborating further about what needed to be done.

That had the effect of addressing race and identity politics—“he was pretty blunt,” one white Bernie supporter told me—without making it clear how he’d address “all that stuff,” as Sanders put it. ““Inartful’ might be a way to say it,” said Sam Reggio, 34, at a Sanders house party in Washington, D.C.’s Petworth neighborhood. Reggio, who is white, supports Sanders for his fight against wealth inequality and support for single-payer health care, but he acknowledges that race and criminal justice are “hot issues for a lot of liberal voters”—issues which Sanders needs to tackle head on. For supporters like Reggio, Bernie’s struggle to grapple with these issue is coming from a real place, like everything else that he likes about the Vermont senator. “He’s a human being—it’s not something built up in a focus group,” he says.

Tom Beach is similarly passionate about Sanders’s dedication to standing up against Wall Street and fighting for ordinary workers. A self-described political novice, Beach felt inspired to host a Sanders house party in his Petworth home. But like Reggio, he also raised an eyebrow when Sanders tried to address race and criminal justice in his remarks. Bland’s story was “just plopped in there,” says Beach. “He felt like he did the race thing.” But Beach believes that the candidate’s ability to broaden his appeal will be a critical test for him—“a measure of his leadership,” he explains.

For Sanders to appeal to more minority voters, they need to be in the audience first. The house parties were the official kickoff for the campaig’s grassroots organizing effort, to expand field organizing beyond the few early—and largely white—primary states of New Hampshire and Iowa. And Wednesday’s gathering in this historically black, rapidly gentrifying corner of Washington made it clear why the Vermont senator needs better outreach. There were recent college grads, married couples, and gray-haired professionals; political greenhorns and seasoned field organizers; fresh transplants and D.C. natives. Many spoke about Bernie’s fight to get big money out of politics; others loved his support for free public college or labor unions. But almost all the two dozen Bernie partygoers were white.

Aaron Allen, 29, was one of the only attendees who was not. Half black, a quarter Latino, and a quarter white, Allen identifies as “all of the above” and hasn’t committed himself to supporting a Democratic 2016 candidate. The problem, he says, is that Sanders isn’t fluent in certain issues because he’s never had to be, representing an overwhelmingly white state. It’s not just with issues like race and criminal justice. “He’ll talk about equal pay for women, but it kind of stops there, as a footnote,” Allen said. He added that Sanders would do that rather than address a thornier cultural issue such as reproductive rights.

Allen thinks Sanders could do more to lay out his personal history and evolution on issues outside of his comfort zone. Yes, Sanders marched to support civil rights in the 1960s, Allen noted, “But why did he march? Why should we still be marching?”

Sanders, by his nature, is practically allergic to personal narrative—the kind of storytelling that’s the backbone of most politicians’ stump speeches. But that kind of biography could help fill in some of the gaps as he tries to build his credibility, introduce himself to new audiences, and diversify his own ranks of supporters. And that will mean continuing to wade into unfamiliar territory, even at the risk of sounding awkward.