In December 2014, a measles outbreak began at Disneyland in Orange County, California. The outbreak eventually sickened 111 people in California and spread to six other states as well as Canada and Mexico.

California quickly became notorious for its high number of vaccination skeptics. Yet, this outbreak is not simply the result of a few outspoken “anti-vaxxers”—celebrities or otherwise—but instead is part of a more general trend of increased distrust over the use of mandatory vaccinations.

The Disneyland outbreak coincided with a decrease in vaccination rates in the United States.

These vaccines have been used safely and effectively for decades. So why is the American public—or at least a significant segment of it—now increasingly skeptical of mandatory school vaccinations? One possible source for this trend is that as vaccination rates have fallen, so have civic engagement and public trust in the government and the medical profession.

Growing skepticism of vaccines

The majority of parents in the U.S. still have their children vaccinated on schedule. But there is a small minority who refuse vaccines altogether, or choose some vaccines and not others, or want a different schedule.

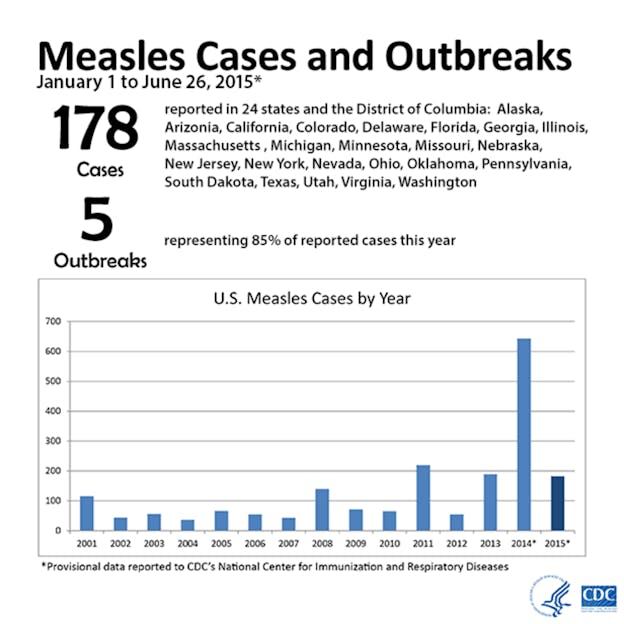

In 2014 there was a record high number of measles cases (668) since the disease was considered eliminated in 2000, with researchers placing the blame on declining vaccination rates.

In some states, the decline has been dramatic. In California, the number of kindergarten-aged children who have failed to complete all their recommended vaccinations has gone up significantly in the last five years.

Other states, such as Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, Arizona, and Washington, have also experienced significant decreases in their vaccination rates that put them well below “herd immunity” (the threshold where enough people are immune to a disease that transmission chains are broken).

In Seattle, the polio vaccination rate (81.4 percent) is lower than in Rwanda. And while California just passed a bill to eliminate religious and personal exemptions to vaccinations (it is now, along with West Virginia and Mississippi, one of only three states that allow only medical exemptions), legislators in Washington state and Oregon have backed away from similar bills.

A recent survey by the independent Pew Research Center suggests that there may be growing doubts about the practice of mandatory vaccines.

Younger Americans (18 to 29) are much more likely than older respondents to believe that childhood vaccinations should be a choice—41 percent think parents should decide. They’re also more skeptical about the safety of vaccines, such as the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine—15 percent think they are unsafe and another 8 percent are unsure. These results suggest the potential for a demographic shift in the U.S. population where, over time, there is less and less support for the use of widespread vaccinations.

If so, why is this trend occurring? Why are we becoming more wary of the practice of compulsory vaccinations, and why are vaccination rates falling so dramatically in some states?

We are more solitary than ever—and trust each other less

In his book Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam argues that since the middle of the 20th century, Americans have become increasingly distant from one another. (In the jargon of sociologists, there has been a dramatic decrease in “social capital.”)

Sometime after the 1950s, Putnam says Americans started to retreat into their own private spheres of family and close friends. Partly because of the increase in entertainment technologies (first television and now the internet), we became less politically engaged, less civically minded, and less involved in community organizations like the Lions Club or the local PTA.

Putnam’s favorite example is bowling leagues. Bowling used to be the most popular sport in the U.S., and Americans used to bowl in leagues and compete against other members of their community. Now hardly anyone bowls in leagues.

What does this have to do with vaccinations? A key feature of Putnam’s theory is “social trust”—the degree to which people think others are honest and reliable. As we have become less civically engaged, our trust in other people has decayed.

We trust institutions less and less

It is not just our trust in people that has decayed, but also social institutions. In 1964, 77 percent of the population said that they had trust that those in the federal government would do what was right; by 2014 this number had fallen to 24 percent.

And the same trend can be seen in trust for the medical profession. Research shows that in 1966, 73 percent of the population trusted the leaders of the medical profession; by 2012 this has fallen to 34 percent, and less than one-quarter (23 percent) of the population has confidence in the U.S. health care system as a whole. This lack of trust puts the U.S. near the bottom among industrialized nations—in terms of trust in doctors, the U.S. ranks 24 out of 29 countries surveyed.

Distrust of the government is one of the main arguments of the anti-vaccination movement. In a piece that is typical of the movement, author and freelance journalist Bertigne Shaffer writes:

The state already controls vast swathes of what we can do with our lives: What professions we may enter, how and where we may conduct business, what substances we cannot ingest, how much of the money we earn we are allowed to keep… If you do not believe that individuals have the right to control what goes into their own bodies then I have to wonder what rights – if any – you do believe people still have.

These arguments made by the anti-vaccination movement have begun to resonate because of our historically low levels of trust in the government and lack of civic engagement. Recent research finds that those who have less faith in the government are less likely to vaccinate in the case of an outbreak of disease.

People still favor government actions, like quarantine

If some Americans are becoming more distrustful of the government’s involvement in their medical lives, the puzzle is that many of us still support other government-sponsored practices such as quarantine.

A CBS news poll conducted during the Ebola outbreak last year found that 80 percent of Americans believed that U.S. citizens returning from West Africa should be automatically quarantined. And there is in fact a long history of the use of quarantine in the United States, dating back to at least the turn of the 20th century.

How have we become wary of the practice of vaccination, while still maintaining our support of isolating the infectious?

Our lack of trust also helps explain this puzzle. As we have lost trust in the people around us, we have become fearful of the sick, distrustful of the infectious. So much so that we are willing to use the power of the state to protect ourselves from the threat that other people’s bodies may pose.

Our bowling-alone society has created fertile ground for falling rates of vaccination. Achieving high rates of vaccination—above the 90 percent that ensures herd immunity—requires that the community think of themselves as being in it together. Everyone gets vaccinated so that everyone is protected. When trust breaks down, that medical social contract we’ve historically had with one another starts to dissolve.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.