Joan Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne had lived in Brentwood, an affluent Los Angeles suburb, for two years, when they opened the newspaper one morning to find someone had played a bizarrely intrusive prank on them. In the pages of the Los Angeles Times, they saw their house—a Colonial-style villa with a grand entrance hall, a swimming pool, and a garden where they grew roses and herbs—“for sale” in the classifieds section. The asking price was low at just under $1 million. The ad implied a drastic change in their circumstances: “BRENTWOOD PARK STEAL! Famous writers’ loss is your gain.”

The ad’s claims of financial downfall didn’t make sense. In the early ’80s, when this happened, the Didion-Dunnes were more successful than ever, known for both their fiction and magazine writing, and long established as a screenwriting duo. Dunne immediately sent the newspaper’s publisher an indignant letter, which didn’t help much. He and Didion never found out who was responsible for the ad.

But the incident did highlight a phenomenon that surrounds many “famous writers”: their readers’ desire to visit, inspect, and sometimes buy their personal property. Interest in Didion’s lifestyle might have been particularly strong, since she was best known for writing from a very personal viewpoint. And the two essay collections that cemented her fame, Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album, bore touches of understated glamor. She wrote about staying in bed with a migraine, and conversation she overheard in hotel bars. In her first column for Life, she wrote about going to Hawaii “in lieu of filing for divorce.” She also saw the limits of this type of writing. The response she’d had from readers was emotionally overwhelming, and “there was no way for me to reach out and help them back,” as she later told an interviewer.

Although she started to take on more political subjects in the late ’70s, the interest in her personal life—and her personal belongings—only grew. In the crossover of feminism, fashion, and literary interests, there is a whole swathe of the internet where Didion is a staple reference. Her borscht recipe can be found on the website Brain Pickings, and her list of items to pack for reporting trips periodically crops up on style blogs. Though often uncomfortable, she didn’t shun all of the attention that came her way. In 1989, she appeared in GAP ads with her 23-year-old daughter, wearing black turtlenecks, and staring defiantly into the camera with only the barest suggestion of a smile. Last year, she wore huge black shades in ads for the French luxury goods brand Céline, which inspired devotion in unexpected places and in-depth analysis from the already devoted. Planning a documentary about Didion, her nephew Griffin Dunne raised funds on Kickstarter by selling, at $2,500 a pair, Didion’s own sunglasses.

If the differences between success and celebrity matter at all, they matter in Hollywood, where Didion worked for decades. A lot of the problems with writing about Didion are the same as writing about any celebrity. What you have access to is the stuff your subject has already released. Access to everything else is tightly restricted—the archive of Didion’s papers at the Bancroft library in Berkeley includes very little correspondence or personal material. The most revealing details about her life come from letters other people have sold or given away. Within these limitations, the best a biographer can do is comb through the material, rearranging in chronological order, rearranging in thematic order, and looking in the spaces between to see if there is a story that can be separated from the brand.

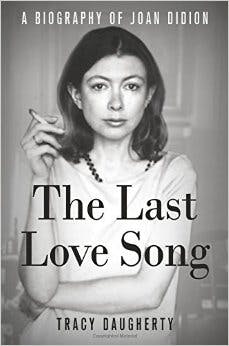

The Last Love Song, Tracy Daugherty’s new, 672-page biography of Didion never gets quite far enough from her own version of events to be a serious literary biography, showing the writer at work. Daugherty, a novelist and creative writing professor at Oregon State, has previously written biographies of Joseph Heller and Donald Barthelme, who was his teacher. In the new book, he draws heavily on Didion’s published accounts of her own life; he wasn’t able to speak to her closest friends and collaborators. Those who did speak to him— the fun in a celebrity biography is seeing who gets thanked in the acknowledgements—are people who’ve been out of touch with Didion for some time: an ex-boyfriend, a couple of figures from the Hollywood party scene of the 1960s, and former colleagues. Although he approached Didion for interview, she “chose not to cooperate.”

His solution to this problem was the ultimate fan’s solution. He decided to write a biography of Didion in her own style, “reproducing her mental and emotional rhythms.” The nearest thing to a biopic in book form, it opens with a Romantic vision of the West, and particularly Sacramento, where Didion was born in 1934. Descended from pioneers on both sides, her family held prominent positions in the community as “bankers, saloon keepers, sheriffs,” and her mother would host “ladies’ teas” on Sundays. Closely-observed details from Didion’s essays appear in Daugherty’s book, translated into swift, journalistic prose. Elsewhere, his impersonation of Didion feels overbaked. It’s hard to imagine her writing bluntly, as Daugherty does, “A circle of rocks. A word in the sand. This is where I was from.”

But the book gets interesting when it turns to Didion’s early career, which began in New York. Her first jobs were at fashion magazines, whose pages were steeped in glamor and consumer culture, and whose desks were manned by ambitious young women, choosing the professional over the domestic sphere. As a junior at Berkeley, in 1955 she applied for a slot on Mademoiselle’s Guest Editor program. During a month in New York, the Guest Editors went to editorial meetings, photo shoots and cocktail parties, while living in the Barbizon Hotel for Women, described in Vanity Fair as “the city’s elite dollshouse.” This was the same program Sylvia Plath worked in two years earlier, during which time she had “wanted to die very badly for a day.”

Didion’s tenure was more congenial. She was asked to profile the short story writer Jean Stafford, who knew a lot about being a provincial among New York intellectuals: this was the subject of her anguished story “The Children Are Bored on Sunday.” To go with her contribution, Didion had to provide a few sentences about herself. Excavated from the Mademoiselle archives, what she wrote shows a still somewhat green, aspiring writer with a sentimental attachment to home: “Joan spends vacations river-rafting and small-boating in the picture-postcard atmosphere of the Sacramento Valley.” Among her interests, she lists “almost any book ever published.”

It’s tempting throughout Daugherty’s biography to grab moments like these and go looking for other versions of Didion, the Joan Didion we don’t see reflected on the surfaces of her own crystalline prose. Her strongest projection of a weary but precise persona is, perhaps, her essay “Goodbye to All That,” a brief memoir of living in New York, when she at Vogue in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Even to people who know that New York affords only few opportunities to appreciate the smell of “lilacs and garbage and expensive perfume,” Didion’s essay evokes all the romance of starting out in a place that’s simultaneously thrilling and impossible. She romanticizes the streets, with “the soft air blowing through the subway grating on my legs.” Her breakdown, when it inevitably comes, seems like the whole point of being in New York: to perform. She cries “in elevators and in taxis and in Chinese laundries,” and sometimes she barely notices whether she is crying or not.

Yet some details in Daugherty’s book expose moments of true panic in this period of Didion’s life. “Hell hell hell hell hell hell,” Didion writes to a friend about leaving California for the Vogue job. Nor was her formation as a writer as smooth as it might look from the essays gathered in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1963), her first collection. Her ex-boyfriend from the 1950s recalls more crying, after American Heritage rejected an article she wrote on grand hotels. Many of her early readers had little patience for her sensitivities and nerves. She clashed with the publisher of her first novel, Run River. “I like fists and chin, stomp and gouge,” he says. Pauline Kael went further, in one of the harshest reviews of Didion’s work. “To be so glamorously sensitive and beautiful that you have to be taken care of,” Kael thought, was the “ultimate princess fantasy.”

By the 1970s, Didion had become uneasy with her generation’s emphasis on the inner life. Renata Adler, a few years younger than Didion, wrote in 1969 of how her generation relied on soap operas for its shared narratives instead of strong social ties. “We have,” she reflected, “no exile we share, no brawls, no anecdotes, no war, no solidarity, no mark.” Similarly, Didion wondered why her classmates at Berkeley had, with few exceptions, never become politically involved. Her 1970 essay “On the Morning After the Sixties” described how they were “distrustful of political highs,” having grown up “convinced that the heart of darkness lay not in some error of social organization, but in man’s own blood.”

But she was slow herself to move into political writing. She and Dunne married in 1963 and moved back to her home state. From Los Angeles, Didion spent much of the next 15 years writing about the social and cultural dislocations of the ’60s, and how quickly a person living through them could slip into nihilism. In her novel Play It As It Lays (1970), Maria Wyeth is saved from complete despair only by the conviction that nothing matters. Her milieu is bars and motels, and the action around her includes a drug overdose, abortion, and suicide. The title essay of The White Album, written between 1968 and 1978, is Didion making sense of the senseless, bringing fragments of experience to bear loosely on the Manson Family killing spree that took place in her neighborhood.

Her transition to politics and current affairs was gradual. Her evocation of a wavering self hardened into a skepticism about the idea of “self-expression.” She opposed the sort of “self-absorption” Woody Allen’s characters exhibited in Annie Hall and Manhattan, a quality that seemed to fascinate people in the “the large coastal cities of the United States,” she wrote in 1979. The same skepticism led her disastrously to miss the point of the women’s movement. She didn’t understand the goals of the radical feminists because they spoke the language of a liberated self. To her, that sounded like “some kind of collective inchoate yearning for ‘fulfillment’ or ‘self-expression.’” Of sexist “condescension and exploitation,” Didion wrote in 1972 that “nobody forces women to buy the package.”

In her fiction, you sometimes get the impression that political drama was most valuable to Didion as a way of keeping internal struggle at bay. A Book of Common Prayer (1977), her first of three overtly political novels, is the story of a woman whose personal mission is swallowed by the political activities of her daughter (plane hijacking) and husband (arms trade). What Didion most admired in fiction and non-fiction was the power of a distanced narrative. Her model was Joseph Conrad’s Victory, which she reread every time she prepared to write a new novel. “The story is told thirdhand,” she explained in a Paris Review interview. The narrator in A Book of Common Prayer, as in her later Democracy (1984) and The Last Thing He Wanted (1996), is just someone who has heard about the story, not someone who is involved in it, or even a friend.

The distancing effect is even more marked in Didion’s later non-fiction. To look back through her articles for the New York Review of Books and The New Yorker from the late ’70s through the ’90s is to notice a distinct pattern. “The narrative is familiar,” she begins an essay on Patty Hearst. The first words of her 10,000-word disquisition on the case of the Central Park Jogger are “We know her story.” There’s an impatience with the established facts, which she holds at an arm’s length. In her essays on American politics, she specializes in skewering political rhetoric and dissecting the work of journalists who follow official narratives too closely. Daugherty praises Didion for getting to the “real story.” But when it comes to asserting political values, these essays feel surprisingly thin. “I think of political writing as in many ways a futile act,” Didion has said.

The hunger for more of Didion’s personal writing persisted. The journalist Linda Hall remembers attending a reading Didion gave in the 1990s. Someone in the audience asked if she would consider revisiting the subject of “Goodbye to All That,” and write now about her return to New York. Didion was surprised: “I did that already,” she replied, citing her 1991 essay on the Central Park Jogger. “The jogger piece was my ‘Hello New York!’”

Didion doesn’t seem to have responded to the demand to give more of herself. Gone were the languorous reminiscences she had the first time around: “I was twenty, and it was summertime, and I got off a DC-7 at the old Idlewild temporary terminal in a new dress which had seemed very smart in Sacramento but seemed less smart already.” The two deeply personal books she later wrote don’t share in the glamor of that earlier work. Blue Nights and The Year of Magical Thinking are both memoirs of grief and regret, written after the deaths of her husband and her daughter the early 2000s. It may be that glamor (“a new dress”) is often dismissed as a surface quality, but it also may be that Didion understood its power as fully as any editor at Vogue, and was able to elevate it to the core of her art.

Now in her eighties, she publishes little. The paradox of Didion might be that she is best known for her shortest writings, while commentary on this early stage of her life grows more voluminous by the day. This is the version of Didion that appears on the cover of Daugherty’s book, a young woman smoking a cigarette nonchalantly. Add to this the distant air she cultivated in subsequent decades, and you see how compatible this slightly unreal version of Didion, who existed on the page and in some photographs for a few years, is with the status of a celebrity: the person who seems to tell everything and gives nothing away.