Hillary Clinton delivered the first major economic address of her presidential campaign on Monday, arguing that family-friendly work policies—like paid leave, affordable childcare, and generous medical leave—are matters of economic growth. For the Democratic frontrunner, “getting closer to full employment is crucial for raising incomes,” reducing inequality, and advancing the status of women. What's less clear, though, is the degree to which putting women to work (even with the guarantee of low-cost childcare and plenty of leave) appeals to women.

On one hand, Clinton is correct in deducing that the United States’ dismal policy scheme when it comes to ensuring paid maternity leave and quality childcare pushes some women out of the workforce. Women whose employers provide generous paid maternity leave do not leave their jobs at the same rates as women whose employers do not. For women who do not receive generous maternity benefits, it is often a better financial decision to give up a job and care for one’s own infant than to go back to work and shell out thousands for childcare, even when the calculation is very close. Instituting mandated paid maternity leave and providing support for childcare could, therefore, prevent involuntary “off-ramping” among women who find themselves in a financial conundrum after giving birth. These are the kinds of policies that would likely succeed at “breaking down barriers” to women’s employment, in Clinton’s parlance.

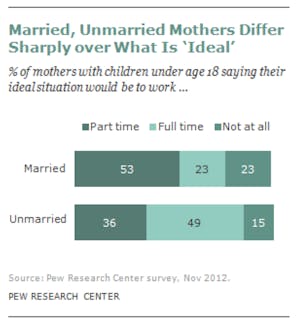

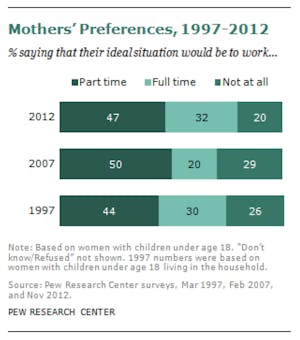

Yet, on the other hand, the post-baby nudge out of the labor market that some women experience does not tell the whole story about women and work. While some women are forced out of the office by childbirth, it appears a significant proportion of women would prefer never to be stuck with full-time work in the first place. Data collected by the Pew Research Center shows not only that women are more likely to work part-time, but that women with children largely prefer to work part-time. The fact that single mothers prefer full-time to part-time work in greater numbers than married mothers suggests that the desire for full-time work is likely a function of financial necessity rather than a matter of pure personal ambition.

Pew’s findings are consonant with global data on women in the work force. In the Netherlands, where people routinely poll as among the happiest on earth, some 76 percent of women work part-time only, along with 26 percent of men. The resultant income and managerial differences between Dutch men and women don’t seem to concern Dutch women, judging by the work of Dutch journalist and psychologist Ellen de Bruin.

Should such differences concern us? It depends, in part, on how you envision women’s liberation. The zest with which American women pursued progress in the workplace now seems, at times, outdated. While it was necessary and useful to break down prejudices that prevented women from pursuing their workplace ambitions, it also appears (especially in our age of widespread suspicion of corporations and the superrich) that the workplace is not where anyone achieves much in the way of meaningful liberation. Work is, for most of us, compulsory: The Great Recession, not a burst of female empowerment, has been a major engine of female labor force re-entry in the last several years. So if women would rather stay home or work intermittently, especially after having children, perhaps female-friendly policy should be crafted around making full-time work itself optional for mothers, as opposed to attaching particular options to work.

One possibility toward that end is a monthly child benefit program, which would help mothers with children stay financially afloat even with reduced hours, and would not rely upon income or hours worked to calibrate one’s allowance. Another potential direction would be to distribute maternity benefits and healthcare through the state rather than the employer, which would free mothers from the necessity of working a particular number of hours in order to qualify for the support they need to start out life with a new child. These policy programs are compatible with expanded support for childcare and the kind of workplace flexibility that would encourage women who want to keep working to stay in their jobs, but they would extend a certain freedom to women who, after giving birth, would rather turn their attentions elsewhere. Now that’s liberation.