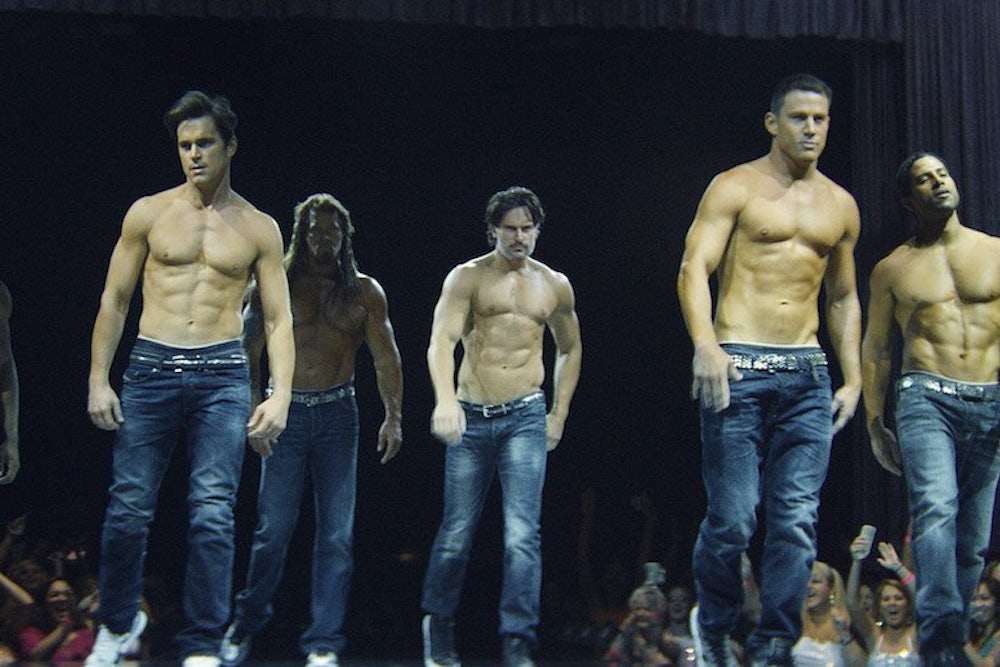

“My god is a she,” Channing Tatum’s stripper-entrepreneur casually asserts midway through Magic Mike XXL, the frenzied sequel to 2012’s sharply drawn tale of Florida’s finest male dancer. The line gets a chuckle, but it’s merely re-stating the obvious: This is a movie devoted to the sacred feminine. It may be directed and written by men, starring men, but everyone involved with this goofy road-trip comedy know exactly who it’s for. Women will flock to the theaters at the ends of busy work-weeks to hoot and holler at ripped bodies and lewd choreography, and Tatum, along with his equally chiseled co-stars, will give us exactly what we want.

The original Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, was a morality play about the twenty-first century American economy, a surprisingly dark exploration of working-class masculinity in an “End of Men” era. It’s protagonist, Mike Lane (Tatum), was stringing together a living with a slew of part-time gigs—construction, auto detailing, stripping—while trying to save up to start his own small business. Everyone was circumscribed by recession realities—jobs that don’t pay benefits, banks that won’t offer loans, the lure of get-rich-quick schemes and easy money. The follow-up has no such anxieties. It’s the movie that the Magic Mike marketing campaign three years ago had prepared us for—a mindless fantasia of glistening abdomens and gyrating crotches. And it’s glorious.

The movie is capably directed by Gregory Jacobs, Soderbergh’s longtime producer and assistant director, who lovingly captures sweaty bodies and glistening beaches and retains the original's loose, relaxed style. Soderbergh stuck around behind-the-scenes as cinematographer and editor (using his well-worn noms-de-plume Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard). But the real authorial vision here seems to be Tatum himself, and his brand of genial, body-confident bro-dom.

Magic Mike: Uno ended with Mike leaving stripping behind to pursue his real dream: custom furniture-making. The requirements of sequel plotting compel him re-join his old buddies, the “Cock Rocking Kings of Tampa,” to perform one last time at a male strippers’ convention in Myrtle Beach. This might be depressing, a disillusioning sign that a commodification-free life, lived on ones own terms, can’t be met, except that the new movie turns stripping—excuse me, male entertainment—into a kind of higher calling. “We’re like, healers or something,” Andre, a strip-club crooner played by Donald Glover, tells new-age himbo Ken (Matt Bomer). “These girls have to live with men throughout their life who don’t listen, who don’t ask them anything. We just have to listen to them.”

It’s a striking reversal from Soderbergh’s original. “I’m not my goddamn job,” Mike angrily insisted during the climax of that film, after his love interest called him a bullshit 30-year-old male stripper. “That's what I do, but it's not who I am.” In XXL, Mike and his band of merry men happily accept their gift: to brighten a woman’s day, to make her smile. That mindset is best captured by the strongest addition to the cast: Jada Pinkett Smith, as Rome, proprietress of a subscription-based strip club for women, a high-end female utopia. She calls her customers queens, and lavishes them with attention. It’s like a day-spa, with lap-dances in place of pedicures.

Like the original, XXL is a feast for the oft-ignored female gaze, fulfilling cinematic desires I never realized I had: to see Kelly Ripa’s morning-show co-host thrust his gold-lame-clad pelvis into a woman’s face; to watch a convenience-store striptease soundtracked to the Backstreet Boys. But the sequel has a somewhat different take on the females doing the gazing. In the original, the entire male-stripping enterprise was slowly revealed to be somewhat seedy and pathetic, and the women who came—sorority girls and housewives—were treated as similarly laughable. In the movie’s least generous moment, one of the dancers lifts a fat women up in the air, only to immediately throw his back out. That attitude is typical for Hollywood, where the sexual hunger of women who are too old, too fat, too plain is treated as obviously absurd. Here, the female extras shrieking at the sight of Tatum’s rippling body, women of all sizes and shapes and races who are being deemed worthy of satisfaction, are treated with a rare kind of respect. “Did you like that ladies? Was it good to you?” Pinkett Smith asks the crowd during the movies orgiastic, almost religious, closing number. “Are you ready to be worshipped?”