The conservative justices of the Supreme Court were no more gracious in victory today than they were in defeat last week. They prevailed in Glossip v. Gross, a case about the legality of a drug called midazolam that some states use in lethal injections, but they still assaulted the integrity of their liberal colleagues. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Alito attacked Justice Sotomayor’s “resort” to “outlandish rhetoric,” which, he said, “reveals the weakness of [her] legal arguments.” Justice Scalia outright mocked Justice Breyer. “His argument is full of internal contradictions and (it must be said) gobbledy-gook,” Scalia wrote, before concluding that Breyer “rejects the Enlightenment.” Justice Thomas, meanwhile, wanted to know why previous courts found it unconstitutional to execute juveniles.

It’s not surprising to see tempers flare in the five Glossip opinions: Death penalty cases have a history of producing a lot of paper. And back in April, Dahlia Lithwick described oral arguments in this particular case as “unpleasant and embarrassing” in Slate. The actual matter before the Court in Glossip was narrow, but the case became an occasion for the justices to express their broader thinking on the death penalty. Justice Breyer, joined by Justice Ginsburg, used the occasion to argue that the death penalty itself was unconstitutional, while Scalia and Thomas lined up against them.

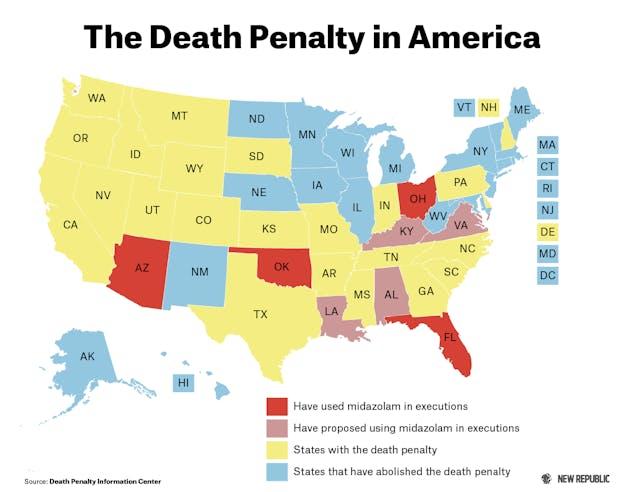

It fell to Justice Alito, writing the majority opinion, and Justice Sotomayor, writing the principal dissent, to tackle Glossip's specific question: Did midazolam pose an intolerable risk of painful execution? The drug came into use in death penalty states after a shortage in the drugs conventionally used in lethal injection. Doctors rarely use midazolam, though, to anesthetize their patients, and the Glossip plaintiffs argued that it was not powerful enough to protect them from feeling the painful effects of the other lethal injection drugs.

Alito rejected their arguments for two reasons. First, he said they failed to establish a safer and available alternative to an execution with midazolam—a requirement that Sotomayor denounced as “patently absurd.” Second, he affirmed the lower courts ruling that midazolam did not pose an intolerable risk of pain and suffering in an execution. The district court had drawn this conclusion by weighing the testimony of a single expert witness, a doctor of pharmacy who said midazolam would work, against two expert witnesses who said it would not.

Essentially, the district court decided the legality of midazolam based on the testimony of just three witnesses, and the Supreme Court saw nothing troubling with this fact. The most prudent course of action, I thought after having witnessed oral arguments in April and having written about the use of midazolam, would have been to remand the case to a lower court, where midazolam’s properties could be more properly investigated. Alito rejected this possibility, however, by arguing that “courts should not ‘embroil [themselves] in ongoing controversies beyond their expertise.’”

Alito’s opinion indirectly acknowledges a limitation of the Court: Execution protocols are being written by corrections officers and attorneys general, not by scientists or doctors. And no one really knows how midazolam works in such large doses, because the medical and scientific communities don’t spend a lot of time studying the lethal applications of otherwise helpful drugs. The result, as Sotomayor wrote, is that “States are engaged in what is in effect human experimentation.” In Arizona, for instance, the execution team injected one prisoner with 15 different doses of midazolam and hydromorphone in an execution that lasted nearly almost two hours.

Alito’s logic might be more persuasive if the Court were, in fact, leaving lethal injection in the hands of medical experts. Instead, his effort to frame the Glossip decision as an act of judicial humility essentially gives state lawyers and prison officials the green light to raid the medicine cabinet in order to carry out death sentences. True humility would recognize that judges are unqualified to evaluate the pharmacological properties of medical drugs—and conclude that states should find another way to carry out their sentences.