The tragedy in Charleston has revived the movement to take the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina statehouse grounds.

On Monday June 22—five days after the shooting in the AME Emanuel Church—South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley called a press conference to announce that,

it is time to remove the flag from our capitol grounds…This flag, while an integral part of our past, does not represent the future of our great state.

This is a particularly sensitive issue because the flag is on state property.

The Confederate flag on public property leads many to ask: What message is the government sending?

The case against flying the Confederate flag

For those who want the flag to come down, the message is a reminder of white supremacy and the war fought to maintain slavery.

States have been taking Confederate flags and monuments down for years now, and refusing new requests to fly them.

Just this term the Supreme Court in Walker v. Texas Sons of Confederate Veterans permitted Texas to reject a specialty license plate proposed by the Sons of Confederate Veterans with a Confederate battle flag on it.

Justice Breyer concluded that what appears on the license plate is a form of government speech and that Texas could decide for itself what speech to permit. When Texas decided that it did not want to include the Confederate battle flag, Breyer concluded there was no first amendment right of members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans to require Texas to include the flag.

Integral to the conclusion that Texas can keep the Confederate battle flag off their license plates are the twin ideas that the government is speaking through the license plates and that Texas can control its own speech.

Such principles were used to justify the 2009 decision of Pleasant Grove City, Utah, to reject a monument from the Summum church for display on public property.

Writing for the majority in City of Pleasant Grove v. Summum, Justice Alito said “the display of a permanent monument in a public park” is likely to be perceived as the government’s speech.

The city could reject a religious monument, because observers would think the government was endorsing that monument.

So far, so good: The state can (and many of us believe ought to) reject the display of the Confederate flag on government property.

Now look at the other side of this.

What is the state saying by flying the Confederate battle flag?

What happens when the state government decides to speak by putting a Confederate battle flag or a monument to the Confederacy on its property (or permitting others to do so)?

What message is the state sending?

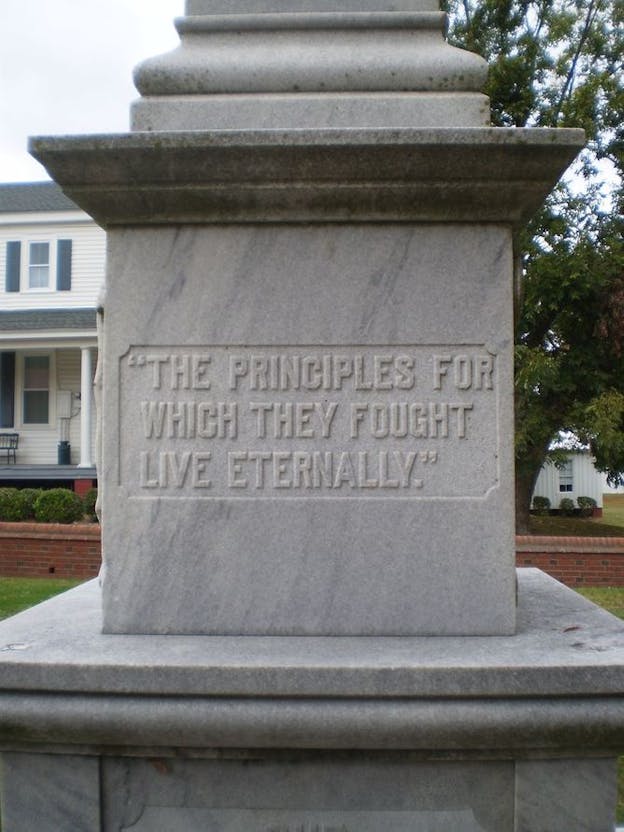

While we’re working on that thought experiment, take, for instance, the Confederate monument in front of the Sussex County, Virginia Courthouse.

Note the inscription: “The principles for which they fought live eternally.”

That makes me suspicious of the quality of justice that African Americans can receive inside that courthouse.

Indeed, many people now see the rise of the use of the Confederate flag during the Civil Rights movement as a response to the increasing claims of African Americans to equality.

And as Justice Alito recognized in the Summum case, monuments on public property will lead observers to “routinely—and reasonably—interpret them as conveying some message on the property owner’s behalf.”

Violation of the 14th amendment?

That leads to the question, then, of whether government speech that tells African Americans they are inferior—and perhaps that the era of slavery was right—violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

This is a stretch of current equal protection doctrine, which is concerned with tangible questions like funding rather than speech.

However, if a state legislature passed a statute proclaiming African Americans are inferior I can imagine that such a bold and vicious statement might rise to the level of a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise that no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Now take a further step: Does the Confederate battle flag or a monument to the Confederacy tell African American citizens that they are inferior? And if so, does that violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

While the answer to the latter question may not be clearly yes, I don’t think it is clearly no, either.

Ultimately, this is really more a question of whether a state—and its politicians—want to continue to fly a flag that is so closely associated with a war begun to maintain slavery.

Many supporters of the flag say that the meaning for them is about southern heritage, not race hatred. And in this I am inclined to believe their statements about their motive.

But at this point in American history the flag has become closely associated in the minds of many with white supremacy, slavery, and Jim Crow segregation. Whatever its meaning once was—or still is in the minds of some—in the minds of many it is time to realize that this is a symbol that is sending the wrong message to U.S. citizens.

Before this becomes a lawsuit, the Confederate flag should be taken down from in front of the South Carolina State House.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.